Yellowstone's Heritage & Research Center as seen through the Roosevelt Arch, photo by Elise Fariello, 2015.

Like most graduate students, I know how important it is to take advantage of all possible opportunities. In a competitive field like Archives and Collections Management, the variety and uniqueness of experience can often make or break an interview or application. When I first saw the listing for a processing internship at the Yellowstone National Park Archives, I knew I had to apply; not only would it provide a distinctive and impressive résumé boost, but it was also just too cool to pass up. As someone with a history of passionate involvement with archives and National Parks, I could not (and still cannot) imagine a more exciting way to spend a week than processing an invaluable piece of American history.

This internship was one part of a larger, inspiring project. Like many repositories, the Yellowstone National Park Archives—housed in the state-of-the-art Heritage & Research Center in Gardiner, Montana—struggles with a backlog of unprocessed collections. To tackle this, the archivists developed an innovative way to ensure progress, create a finding aid, unveil research potential, and make these collections available to the public. Dubbed an “Archives Blitz,” the Yellowstone staff host teams of five volunteers for one-week periods and dedicates that week to the completion of a project. The great benefit of the Archives Blitz experiment is that it helps Yellowstone’s archives and educates volunteers, while also serving as a model for the entire archival community; this is one way to face head-on the ever-present challenge of backlogs. The Archives Blitz was a chance to get in on the ground floor of a revolutionary method of archival processing.

I arrived in Gardiner in January as part of Archives Blitz Team 4. On our first day there, we were fortunate enough to have archivist Shawn Bawden introduce us to the park. Before we even arrived in the archives we were immersed in Yellowstone’s rich history and landscape; we saw bison, moose, elk, and sheep—we even heard wolves howling. It is impossible not to be in awe of Yellowstone’s natural diversity; in the winter, these sights—while undoubtedly always beautiful—were truly magical. The snow made the landscape sparkle in the sunlight and allowed the wildlife to stand out clearer against the white. That extensive tour of the Park was an experience I will always treasure.

The next day we went right to work. The collection we were processing, the Records of the Superintendent’s Office, seemed daunting at first. The documents spanned over a hundred years and many different mediums. The boxes were piled two-deep across three tables. However, using the technique of MPLP (More Product, Less Process) and with the guidance of archivists Anne Foster and Shawn Bawden we quickly got into the swing of divvying up the boxes by topic. There are few things more satisfying than transforming a disorderly room full of boxes into a processed collection. As the week went on, the collection became easier to comprehend. Soon, the topics were distinct enough that they became different series and each volunteer was assigned one to work on. These series, too, became more and more logically ordered. By the end of the week, we were immensely proud that our unruly bunch of boxes had become something functional.

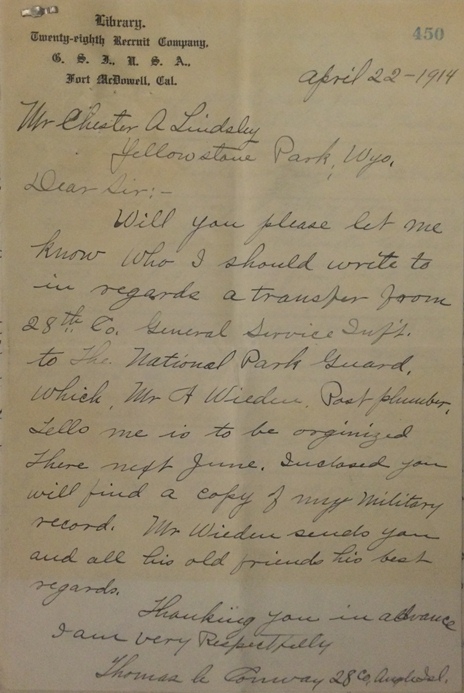

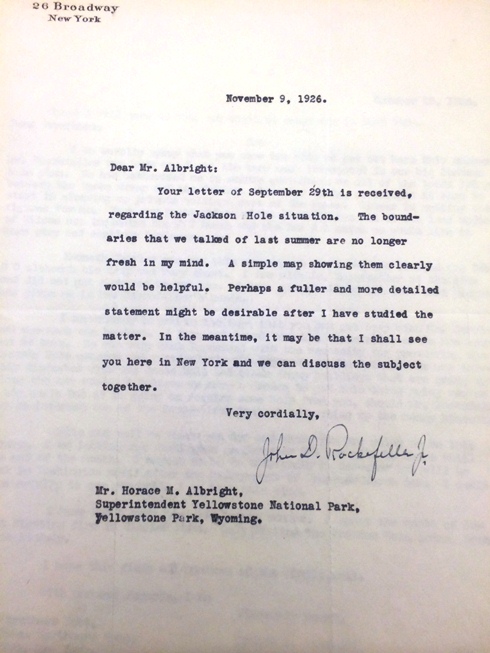

As I delved into my series, the Superintendent’s Professional Correspondence and Documents, my appreciation of the Park’s history and value continued to grow. The passion that Yellowstone has inspired in people—employees and visitors—for well over a century is humbling to experience. I read letters from soldiers begging to be stationed at Yellowstone from when the army managed the Park, letters from famous investors (as a native New Yorker I was particularly star-struck by a letter from John D. Rockefeller Jr.), and a century’s worth of fervent correspondence to and from Yellowstone Park Superintendents. As a student hoping to work with cultural heritage, the superintendents’ never-ceasing advocacy for the Park was inspirational.

Processing the collection was an unparalleled learning experience. It was supplemented by getting to know my fellow volunteers, our continual exploration of the Park grounds, tours of Yellowstone’s museum collections, and face-time with Park historians, registrars, botanists, rangers, librarians, and archivists. I know that the skills I gained at the Yellowstone Archives will continue to open doors for me and my proficiency in blitz-style processing will be valuable in my future work. I look forward to seeing what collections and fascinating historical documents future Blitz teams will uncover and how researchers will use these newly processed materials. I am so grateful to have been part of the Archives Blitz and a little part of Yellowstone National Park’s extraordinary history.