NPS / Diane Renkin Yellowstone National Park preserves the most extraordinary collection of hot springs, geysers, mudpots, and fumaroles on Earth. More than 10,000 hydrothermal features are found here, of which more than 500 are geysers. Microorganisms called thermophiles, or heat lovers, make their homes in the hydrothermal features of Yellowstone. Although individually they are too small to be seen with the naked eye, so many are grouped together in the park's hydrothermal features—trillions!—that they often appear as mats of color. These microorganisms are also called extremophiles because they inhabit environments that are extreme to human life. Imagine living in water at near-boiling temperatures, with the alkalinity of baking soda, or with acidity that can burn holes in clothing. Microorganisms in Yellowstone not only exist in such conditions, but require these extremes to thrive.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

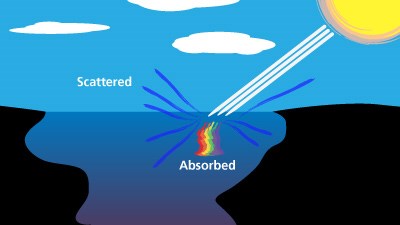

Hot SpringsHot springs are the most common hydrothermal features in Yellowstone. Beginning as rain at the surface, the water of a hot spring seeps through the bedrock underlying Yellowstone and becomes superheated by the Yellowstone magmatic system. An open plumbing system allows the hot water to rise back to the surface unimpeded. Convection currents constantly circulate the water, preventing it from getting hot enough to trigger an eruption. At times, fierce, boiling waters within a hot spring (such as Crested Pool) can explode and shoot water into the air, acting much like a geyser. It is believed, however, that in the case of Crested Pool, no constrictions block the flow of water to the surface. The spring's wide mouth and 42-foot depth provide a natural conduit for superheated water to circulate continuously to the surface. Crested Pool: A Thermal Comparison

Left image

Right image

NPS Hot Springs ColorsMany of the bright colors found in Yellowstone's hydrothermal basins come from thermophiles—microorganisms that thrive in hot temperatures. An abundance of individual microorganisms grouped together appear as masses of color. Different types of thermophiles live at different specific temperatures within a hot spring and cannot tolerate much cooler or warmer conditions. Yellowstone's hot water systems often show distinct gradations of living, vibrant colors where the temperature limit of one group of microbes is reached, only to be replaced by another group.

Life in Extreme Heat

Hydrothermal features are habitats for microscopic organisms called thermophiles: "thermo" for heat, "phile" for lover.

NPS / Jim Peaco MudpotsA mudpot is a natural double boiler! Surface water collects in a shallow, impermeable depression (usually due to a lining of clay) that has no direct connection to an underground water flow. Thermal water beneath the depression causes steam to rise through the ground, heating the collected surface water. Hydrogen sulfide gas is usually present, giving mudpots their characteristic odor of rotten eggs. Some microorganisms use the hydrogen sulfide for energy. The microbes help convert the gas to sulfuric acid, which breaks down rock into clay. The result is a gooey mix through which gases gurgle and bubble. After coming upon Mud Volcano during his 1871 expedition to Yellowstone, Ferdinand Hayden described the mudpot as "the greatest marvel we have met with." Minerals tint the mudpots with such a large palette of colors that the mudpots are sometimes called "paint pots." Iron oxides cause the pinks, beiges, and grays of the Fountain Paint Pot.

NPS / Jim Peaco Fumaroles (or Steam Vents)A fumarole, or steam vent, exists when a hydrothermal feature has so little water in its system that the water boils away before reaching the surface. Steam and other gases emerge from the feature's vent, sometimes hissing or whistling. Steam vents are often superheated, with temperatures as high as 280°F (138°C). Located in Norris Geyser Basin, Black Growler is one of Yellowstone's most famous steam vents. This feature has a history of shifting its location several times. It has been active since 1878 at least, often roaring in a noisy stream of hot vapor. Another wonderful place to enjoy the marvels of fumaroles is at Roaring Mountain, where fumaroles dot an entire mountainside. It is especially dramatic on cool days when the steam is more visible. Travertine TerracesTravertine terraces are formed from limestone. Thermal water rises through the limestone, carrying high amounts of the dissolved limestone (calcium carbonate). At the surface, carbon dioxide is released and calcium carbonate is deposited, forming travertine, the chalky white mineral forming the rock of travertine terraces. The formations resemble a cave turned inside out. Colorful stripes are formed by thermophiles, or heat-loving organisms.

Mammoth Hot Springs TerracesAs one early visitor described the Mammoth Hot Springs, "No human architect ever designed such intricate fountains as these. The water trickles over the edges from one to another, blending them together with the effect of a frozen waterfall." The hot springs were an early commercialized attraction for those seeking relief from ailments in the mineral waters. Today, to preserve these unique and fragile features, soaking in the hot springs is prohibitted. Mammoth Hot Springs are a surface expression of the deep magmatic forces at work in Yellowstone. Although these springs lie outside the Yellowstone Caldera boundary, scientists surmise that the heat from the hot springs comes from the same magmatic system that fuels other Yellowstone hydrothermal areas. A large fault system runs between Norris Geyser Basin and Mammoth, which may allow thermal water to flow between the two. Also, multiple basalt eruptions have occurred in this area. Thus, basalt may be a heat source for the Mammoth area. Hydrothermal activity in Yellowstone is extensive and has been present for several thousand years. Terrace Mountain, northwest of Golden Gate, has a thick cap of travertine. The Mammoth Hot Springs extend all the way from the hillside where we see them today, across the historic Parade Ground, and down to Boiling River. The Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel, as well as all of Fort Yellowstone, is built upon an old terrace formation known as Hotel Terrace. There was some concern when construction began in 1891 on the fort site that the hollow ground would not support the weight of the buildings. Currently, several large sink holes (fenced off) can be seen on the historic Fort Yellowstone Parade Ground.

Mammoth Hot Springs

Virtually wander around Mammoth Hot Springs, where the underlying limestone allow large terraces to form above ground. GeysersSprinkled amid the hot springs are the rarest fountains of all, the geysers. What makes geysers rare and distinguishes them from hot springs is that somewhere, usually near the surface in the plumbing system of a geyser, there are one or more constrictions. Geysers are hot springs with constrictions in their plumbing, usually near the surface, that prevent water from circulating freely to the surface where heat would escape. The deepest circulating water of the system can exceed the surface boiling point of water (199°F/93°C). Surrounding pressure increases with depth, much as it does with depth in the ocean. Increased pressure exerted by the enormous weight of the overlying water and rock prevents the water from boiling. As the water rises due to heating, steam forms and expands, increasing pressure in the constricted plumbing near the surface. At a critical point, the confined bubbles actually lift the water above the surface vent, causing the geyser to splash or overflow. This decreases pressure on the system, and violent boiling results. Tremendous amounts of steam force water out of the vent, and an eruption begins. Water is expelled faster than it can enter back into the geyser's plumbing system, and the heat and pressure gradually decrease. The eruption stops when the water reservoir is depleted or when the system cools. There are more geysers in Yellowstone than anywhere else on Earth. Old Faithful, certainly the most famous geyser, is joined by numerous others big and small, named and unnamed. Though born of the same water and rock, what is enchanting is how differently they play in the sky. Riverside Geyser, in the Upper Geyser Basin, shoots at an angle across the Firehole River, often forming a rainbow in its mist. Castle Geyser erupts from a cone shaped like the ruins of some medieval fortress. Grand Geyser explodes in a series of powerful bursts, towering above the surrounding trees. Echinus Geyser spouts up and out to all sides like a fireworks display of water. And Steamboat Geyser, the largest in the world, pulsates like a massive steam engine in a rare, but remarkably memorable eruption, reaching heights of 300 to 400 feet.

Old Faithful Loading…

Castle Loading…

Grand Loading…

Daisy Loading…

Riverside Loading…

Great Fountain Loading…

Notes on Predictions: - Predictions are not available when the Old Faithful Visitor Education Center is closed, typically early November through mid-December and mid-March through mid-April. - The last prediction made will remain up until a new prediction is available.

Steamboat Geyser

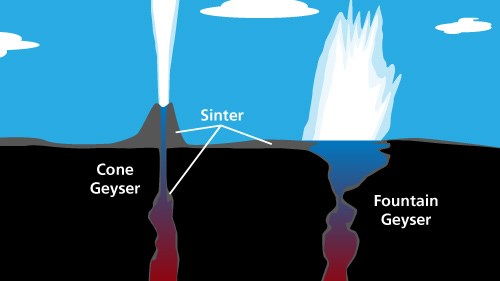

Unpredictable and dormant for years, Steamboat Geyser has been quite active since 2018. Cone GeysersCone geysers, such as Riverside in the Upper Geyser Basin, erupt in a narrow jet of water, usually from a cone. The plumbing system of a cone-type geyser usually has a narrow constriction close to the geyser's vent. During eruptions, the constriction acts like a nozzle, causing the water to jet in great columns. The cone is formed by the constant deposition of silica around the geyser's vent. While traveling underground through rhyolite, a high silica volcanic rock, the superheated water dissolves the silica, then carries it to the surface. Although some of the silica lines the underground plumbing system, a portion may be deposited as sinter around the outside of a geyser to form a distinctive cone. The splashing of silica-rich thermal water may also form spiny, bulbous masses of "geyserite."

NPS The vents within these massive cones are often very narrow, causing the water to splash and spray as it emerges. Every splash and each eruption adds its own increment of silica, enlarging the cones as the years pass. The cones of many of Yellowstone's geysers are hundreds of years old. Beehive Geyser is an example of a cone geyser. It was so named because its four-foot high cone resembles an old fashioned beehive. Though its cone is modest compared to others in the Upper Geyser Basin, Beehive is one of the most powerful and impressive geysers in the park. Typically, Beehive's activity is not predictable, but when eruption cycles start, intervals between eruptions can range from 10 hours to five days. An average eruption lasts about five minutes. Fountain GeysersFountain geysers, such as Great Fountain Gesyer in the Lower Geyser Basin, shoot water in various directions, typically from a pool. A fountain-type geyser has a large opening at the surface that usually fills with water before or during an eruption. Steam bubbles rising through the pool during the eruption cause separate bursts of water that generally spray out in all directions. Fountain type geysers are the most common type of geyser and can range in size from very small to very large. Old Faithful Frequently Asked QuestionsBasic prediction of Old Faithful is dependent upon the duration of the previous eruption. During visitor center hours, geyser statistics and predictions are maintained by the naturalist staff. People speak of the average time between eruptions. This is misleading. Intervals can range from 60-110 minutes.

Visitors can check for posted prediction times in most buildings in the Old Faithful area or download the official NPS app. Old Faithful can vary in height from 106-184 feet (32–56 m) with an average near 130 feet (40 m). This has been the historical range of its recorded height. Eruptions normally last between 1.5 to 5 minutes.

It depends on what you call faithful. The famous geyser currently erupts around 17 times a day and can be predicted with a 90 percent confidence rate within a 10 minute variation. Because of changes in circulation that resulted from the 1959 Hebgen Lake and 1983 Borah Peak earthquakes, as well as other local and smaller earthquakes, the average interval between eruptions has been lengthening during the last several decades.

In the past, Old Faithful displayed two eruptive modes: short duration eruptions followed by a short interval, and a long duration eruption followed by a long interval. However, after a local earthquake in 1998, Old Faithful’s eruptions are more often of the long duration, long interval type. If an eruption lasts less than 2.5 minutes then there will be a 60 minute interval. If an eruption lasts more than 2.5 minutes, there will be a 90 minute interval. It depends on the duration of the eruption. Scientists estimate that the amount ranges from 3,700 gallons (for a short duration of 1.5 minutes) to 8,400 gallons (for a longer duration of 4.5 minutes).

During an eruption, the water temperature at the vent has been measured at 204°F (95.6C). The steam temperature has been measured above 350°.

Geyser Video - Yellowstone Indepth

Learn about the mechanics of geysers, their role in the park's history and what they teach us about the world in which we live.

Current Geyser Activity

Get the latest geyser eruption predictions.

Webcams

Grab a front row seat for the next eruption of Old Faithful.

Geology

A volcano, geysers and other thermal features, earthquakes, and glaciers shape Yellowstone's landscape.

Hydrothermal Systems

Yellowstone's hydrothermal systems are the visible expression of the immense Yellowstone volcano. |

Last updated: April 17, 2025