NPS Fire has been a key factor in shaping the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). Several native plant species evolved adaptations so they survive and, in some cases, flourish after periodic fires. Fire influences ecosystem processes and patterns, such as nutrient cycling and plant community composition and structure. Fire regimes in the western United States changed with the arrival of European and American settlers. Most naturally occurring fires were suppressed to the extent possible. The National Park Service (NPS) aims to restore fire’s role as a natural process in parks when and where this is feasible. In Yellowstone, lightning may ignite dozens of forest fires during a single summer, but most of them go out naturally after burning less than half an acre. Others torch isolated or small groups of trees, become smoldering ground fires, and eventually go out on their own. On rare occasions, wind-driven fires have burned through large areas of forest, as in 1988, when multiple fires crossed more than one million acres in Yellowstone and on surrounding federal lands despite massive efforts to extinguish them. Without frequent small and occasional large fires to create a mosaic of plant communities in different growth stages, biodiversity declines and leaf litter and deadfall accumulate much faster than they can return nutrients to the soil through decay. Evidence of fires that burned before the park was established in 1872 can be found in soil profiles, charcoal found in lake sediments, landslides, and old-growth trees. Research shows large fires have been occurring in Yellowstone since forests became established following the last glacial retreat 14,000 years ago. Yellowstone’s fire season typically lasts from July to the end of September. The number and extent of fires that occur each year depend on climate and what efforts are made to suppress the fires, as well as weather conditions such as the number and timing of lightning storms and the amount and timing of precipitation.

IgnitionAfternoon thunderstorms that release little precipitation occur frequently in the northern Rockies. Yellowstone receives thousands of lightning strikes in a typical summer, but most do not result in fires. A snag may smolder for several days and then burn out because fuels are too moist to sustain combustion or too sparse to allow the fire to spread. Most of the park’s forests have few shrubs; understory fuels are predominantly young trees. The moisture content of both live and dead vegetation tends to drop as summer progresses, temperatures increase, and relative humidity decreases. Fuels have often dried out enough to ignite the first wildfire of the year by July. A forested area that has burned recently enough to contain only young stands of trees usually doesn’t have enough combustible fuel to carry a fire, except under extreme weather and climate conditions. But as the years pass, trees that don’t survive the competition for light and other resources die and eventually fall over. On living trees, older branches die and fall off as they are shaded by new foliage growing above. As a stand grows older and taller, the canopy becomes more broken. This allows enough light to reach the forest floor for a shade-tolerant understory to be established. The accumulation of fuel on the forest floor and the continuity of fuels among the ground, understory, and canopy make older stands more vulnerable to fire. Some forests in Yellowstone may not have burned in at least 300 years and may be particularly prone to lightning ignition.

Fire BehaviorNearly all of Yellowstone’s plant communities have burned at one time or another, but their varied characteristics cause fires to behave differently in them. To quickly assess a fire start and its potential to spread, park staff use different vegetation communities as indicators of fuel load, dominant vegetation, and time since the last fire or other disturbance. The moisture content of dead and downed woody debris, climate, and weather trends are the main factors determining the severity of a given fire season. While fires can occur no matter the fuel moisture, many times conditions are too wet for fires to spread. In fact, 88% of all fires burn fewer than 10 acres in the park. However, in Yellowstone, when 1,000-hour fuel moistures fall below 12%, fires can grow quickly. If extreme drought continues, most forest types and ages are likely to burn. To determine how much water is in the fuel, Yellowstone fire monitoring staff weigh and oven-dry fuel samples to determine the moisture content. In a normal fire season, 1,000-hour fuels within the park may average 14–20% fuel moisture. (Dead fuels are classified according to size, and how long they take to dry out when completely soaked; “1,000-hour fuel moisture” refers to the moisture in large fuels such as downed timber that would generally dry out within 42 days. Kiln-dried lumber is 12%.) Fire behavior is generally not observed until 1,000-hour fuel moisture contents are less than 18%, and only minimal areas are burned until moisture levels drop to 12%. At that point, a fuel moisture threshold is crossed; lightning strikes in forested areas can quickly result in observable smoke and, if fuel and vegetation conditions are right, the fire spreads. Below 12%, fuel moisture, younger and more varied forest types may burn, especially when influenced by high winds. During extreme drought years, 1,000-hour fuel moistures may drop as low as 5%. Depending on the forest type, fuel moisture, weather, and topography, fires can grow in size by isolated or frequent torching and spotting (transport of burning material by wind and convection currents), or by spreading from tree crown to crown. Fires in Yellowstone’s subalpine forests seldom spread significantly through ground fuels only. Like weather, terrain can be either an ally or adversary in suppressing unwanted wildfires. A few natural barriers such as the ridge from Electric Peak south to Mt. Holmes; Yellowstone Lake; and the Absaroka Mountains along the eastern boundary of the park are likely to prevent the spread of a low-to-moderate-intensity fire, but fire may cross these features by spotting, covering two to three miles. Fire managers may be able to predict a fire’s behavior when they know where the fire is burning (vegetation, topography) and the fuel moisture content. However, predicting fire is much more difficult during prolonged drought periods, such as was experienced in 1988, 2003, and 2016. Ongoing research in Yellowstone is also showing that forests experiencing stand-replacing fires can affect fire behavior for up to 200 years. When a fire encounters a previously burned forest, its intensity and rate of spread decrease, except under prolonged drought conditions. In some cases, the fire moves entirely around the burned area. Thus, fire managers have another tool for predicting fire behavior: they can compare maps of previous fires with a current fire’s location to predict its intensity and spread.

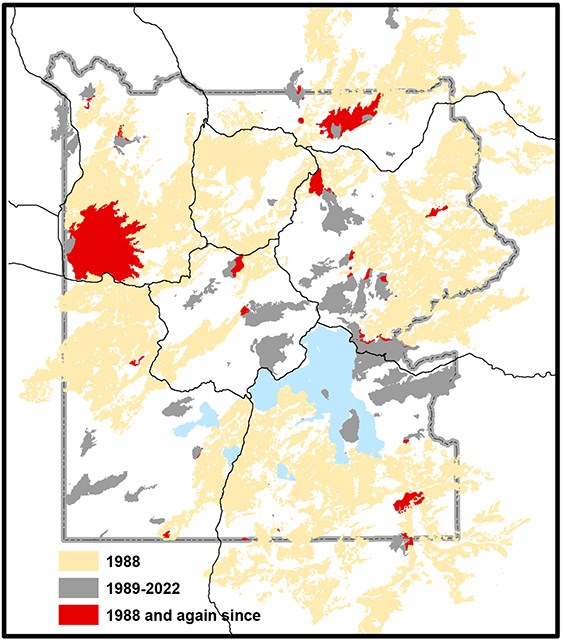

Frequency of FireFire return intervals since European American settlement have ranged from 20–60 years for Douglas-fir and meadows on the northern range to 300 years or more for lodgepole pine forests on the central plateau and subalpine whitebark pine stands. Douglas-fir typically burns frequently but with low intensity (e.g., ground fires). Lodgepole pine burns every few hundred years at high intensity (e.g., crown fire). Until 1900, written records on fires in Yellowstone were sketchy, with generally only large fires reported. From 1900 through 1972, fire records became slightly more reliable, but only records from 1972 until present day are considered reliable and used for fire occurrence statistics. From 1972 through 2022, the park has averaged 24 fires per year, and 5,466 acres burned per year. These data exclude 1988 as it is such an outlier year for number of acres burned within the park. These yearly data range from five fires (2014) to 78 (2003) fires per year, and one acre burned (several years between 1972 and 2020) to 793,880 acres burned (1988) per year. The largest fire in the park’s written history prior to 1988 occurred when approximately 18,000 acres burned near Heart Lake in 1931. In 1989, fire ecologists William Romme and Don Despain suggested that without the fire suppression efforts that began in the 1880s, large fires might have occurred during the dry summers of 1949, 1953, 1960, or 1961. They believe that fire behavior in 1988, in terms of heat release, flame height, and rate of spread, was probably similar to the large fires that burned in Yellowstone in the early- to mid-1700s. In 1988, 50 fires burned a mosaic covering just under 800,000 acres in Yellowstone as a result of extremely warm, dry, and windy weather. Some of the largest fires originated outside the park, and a total of about 1.4 million acres burned in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Some of the areas that burned in 1988 have burned again during the drought conditions of subsequent years, although unique conditions are required for such areas to reburn. Rare, high wind events (greater than 20 mph), more than 80% ground cover of cured elk sedge (Carex spp.), or a continuous fuel bed of 1000-hour logs during very dry conditions, seem required for fires to again carry through areas burned in 1988. Understanding the conditions necessary for recently burned areas (less than 50 years old) to reburn, modeling for the type of fire behavior seen in these areas, and the regrowth of vegetation after a short return interval fire is a current area of interest for fire managers in Yellowstone. Frequently Asks QuestionsFires are a natural part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and vegetation has adapted to fire and in some cases may be dependent on it. Fire promotes habitat diversity by removing the forest overstory, allowing different plant communities to become established, and preventing trees from becoming established in grassland. Fire increases the rate that nutrients become available to plants by rapidly releasing them from wood and forest litter and by hastening the weathering of soil minerals. This is especially important in a cold and dry climate like Yellowstone’s, where decomposition rates are slower than in more hot and humid areas. Additionally, natural fires provide an opportunity for scientists to study the effects of fire on an ecosystem. Burned trees and those that have died for other reasons still contribute to the ecosystem. For example, dead standing trees provide nesting cavities for many types of animals; fallen trees provide food and shelter for animals and nutrients for the soil. However, park managers will remove dead or burned trees that pose safety hazards along roads or in developed areas.

Ecological Consequences of Fire

Fire plays a vital role in a functioning ecosystem, and many plants have adapted to - or become dependent on - fire.

Fire Management

Learn how the park balances the benefits and threats of fire on the landscape.

Current Fire Activity

A list of active fires in the park.

The 1988 Fires

The 1988 fires affected approximately 800,000 acres (or ~36%) of the park.

Nature

Discover the natural wonder of Yellowstone, from the geology beneath the plant communities to the animals migrating through the ecosystem. Source: NPS DataStore Collection 7830. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore. |

Last updated: March 12, 2026