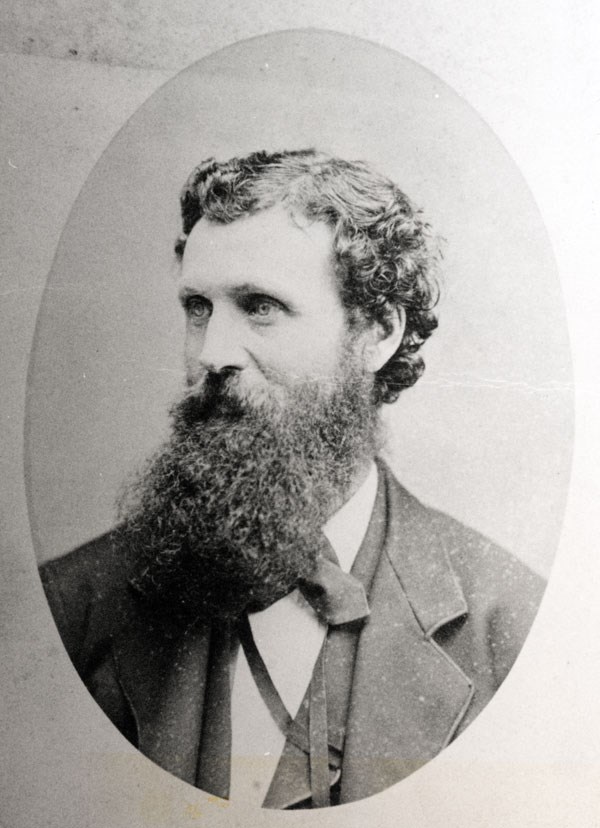

John Muir has inspired Yosemite’s travelers to see under the surface through his poetic imagery: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine into trees.” Muir, who came to California seeking the solitude of nature, decided to stay—dabbling as a glaciologist, a wilderness activist, and a writer who published persuasive ecological articles with a quill made from a golden eagle feather found on Yosemite’s Mount Hoffmann. Born in Scotland in 1838, Muir immigrated to Wisconsin with his family when he was 11 years old. Life on the homestead did not inspire him, and Muir soon found employment in a factory. The change proved to be inspiring but in an entirely unexpected way. After he was nearly blinded by an industrial accident, Muir found himself driven to learn everything he could about a world unaltered by man or machine. He briefly studied natural sciences at the University of Wisconsin but, ultimately, chose to spend his lifetime enrolled in what he called the “University of Wilderness.”

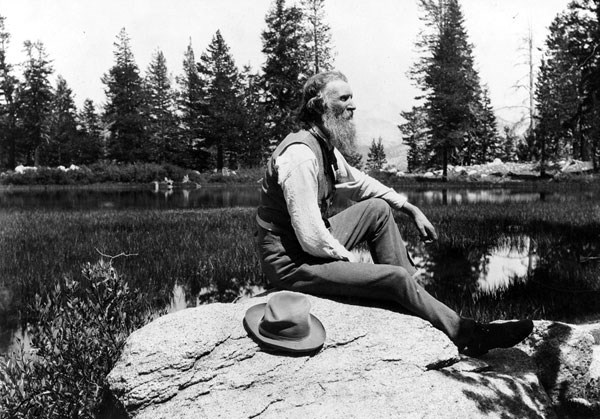

Image credit: NPS Photo Muir first visited Yosemite in 1868. He was so impressed with his week’s visit that he decided to return the following year, finding work as a ranch hand, as he settled in the area. The next year, he landed a shepherd job for $30 per month that suited him fine. While Muir guided a flock of 2,000 sheep to the Tuolumne Meadows in the High Sierra, he studied the flora and fauna and sketched the mountain scenery. (His experiences and illustrations were later published in My First Summer in the Sierra.) After a stint as a shepherd, Muir found regular work at a newly constructed sawmill alongside the present-day Lower Yosemite Fall trail in the Valley. During the two years he worked at the mill owned by James Mason Hutchings, Muir started building his own Yosemite Creek cabin, if only so he could hear the sound of the water as he slept. Muir’s newfound prominence as a Yosemite spokesman bothered Hutchings, who fancied himself the definitive authority on the subject. Tempers flared, and Muir quit in 1871. In September 1871, two months after leaving the sawmill, Muir wrote his first article for publication on glaciers, published in the New York Tribune. His ability to cultivate connections with literary, scientific, and artistic celebrities rapidly enhanced Muir’s reputation as a naturalist. Botanists Asa Gray and Albert Kellogg, artist William Kieth, poetess Ina Coolbrith, editors Charles Warren Stoddard and Henry George, writer Jeanne Carr, educators J.B. McChesney and John Swett, and photographer J.J. Reilly all became early confidants.

Throughout the 1870s, the popularity of Muir’s newspaper publications grew steadily. The prolific writer became particularly concerned about natural landscape preservation. Published in the Sacramento Record-Union in 1876, “In God’s First Temples: How Shall We Preserve Our Forests?” chided California legislators for standing by while the state’s woodlands were recklessly depleted. During the 1880s, he focused his attention on the destruction of natural resources in areas surrounding the state-administered Yosemite Grant, set aside in 1864. Muir was alarmed at the extensive damage livestock animals caused to the delicate High Sierra ecosystems, especially the “hoofed locusts” he had so carefully guarded a few years earlier. In 1889, Muir took Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine, to Tuolumne Meadows so he could see how sheep were damaging the land. Muir convinced Johnson that the area could only be saved if it was incorporated into a national park. Johnson’s publication of Muir’s exposés sparked a bill in the U.S. Congress that proposed creating a new federally administered park surrounding the old Yosemite Grant. Yosemite National Park became a reality in 1890. While in the midst of his environmental efforts that turned political, Muir’s match-making friend, Jeanne Carr, insisted that the bachelor find a mate. Muir married Louisa Strentzel in 1880. Nine years his junior, “Louie” was the 32-year-old daughter of a notable Polish horticulturist and fruit ranch owner in Martinez, California. After his marriage, Muir’s visits to Yosemite became less frequent, but Muir returned with his wife to Yosemite in 1884. Louie’s fear of bears and her difficulty climbing at Muir’s pace, however, made her first trip to Yosemite her last. The wedded Muir continued to pursue his scientific study with fervor, and just three months after his marriage, he traveled to Alaska as a correspondent for the San Francisco Bulletin and again the following year with the Bulletin team to look for the lost naval exploration ship USS Jeanette. Continuing adventures out of state, Muir achieved an historic ascent of Mount Rainier in Washington in 1888 and numerous journeys to Alaska.

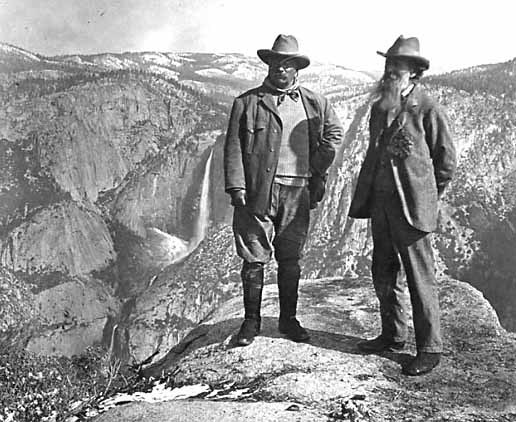

The last 25 years of Muir’s life were consumed with constant travel, writing, and oversight of the Sierra Club—for which he served as president from its creation in 1892. He lobbied successfully for the creation of Yosemite Park in 1890 and then asked for additional protections when he toured President Theodore Roosevelt in the park in 1903. Muir’s persuasive words to Roosevelt and state authorities led to the return of Yosemite Grant to the federal government in 1906. His published writings were also instrumental in the creation of Grand Canyon and Sequoia national parks. At the end of his life, Muir and the Sierra Club fought a bitter and ultimately unsuccessful crusade against construction of the O’Shaughnessy Dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. This was reportedly the first major battle of the environmental movement. On Christmas Eve, 1914—just more than a year after Congress authorized the dam’s construction—Muir died. Even though he died in a Los Angeles hospital, the great wanderer had remained active and on the move until the last few months of his life. Although Muir only truly lived in Yosemite for a few years, from 1868 to 1874, his short time in the Sierra changed him forever more. Muir has inspired us to protect natural areas not for their beauty alone but also for their ecological importance. In The Yosemite, published in 1912, he wrote: “But no temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite. Every rock in its wall seems to glow with life.” More Information

Sources

“Ere dawn had kissed the level valley floor / He climbed to summits through the sleeping wood / By the inerrant guide of forest lore, / And found companionship in solitude / He feared no beast and by no beast was feared / And none was startled when his shape appeared.” -- Excerpted from the poem, “With Muir in Yosemite,” by Robert Underwood Johnson (as printed in the 1938 Yosemite Nature Notes, 17) |

Last updated: September 23, 2025