Go back to a time of horse-drawn wagons, a covered bridge, and rustic cabins. The Yosemite History Center is a collection of historic buildings where outdoor interpretive signs tell the stories of people who moved here from around the world and shaped the park’s development. During the summer, visit exhibits inside the Chinese Laundry and the Acting Superintendent's Office, take a ride on our horse-drawn wagon, or watch blacksmiths forge iron tools on a coal forge! Check the Yosemite Guide for details. Many of the buildings that make up the Yosemite History Center were moved to Wawona in the 1950s and '60s from various locations throughout the park. These buildings were moved to make way for more modern park facilities and to create an area to interpret Yosemite's history. The History Center commemorates the efforts of people, the events they experienced, and the issues they faced during the establishment of Yosemite as a national park.

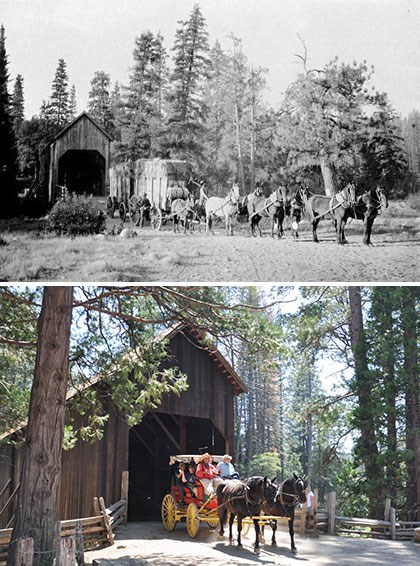

Wawona Covered BridgeIn the mid-1800s, entrepreneur Galen Clark funded construction of a bridge in Wawona (then uncovered) as part of a road that he hoped to complete between Wawona and Yosemite Valley. At that time, the only way to get to Yosemite Valley was by foot or horseback on narrow trails. Building a road would provide comfortable, swift access to Yosemite Valley via stage. Clark’s funds soon dried up, and businessman Henry Washburn took over the project and had the road finished in 1875. The Wawona bridge was covered a few years later, perhaps to remind Henry of the bridges in his home state of Vermont. The road from Wawona to Yosemite Valley was built by 300 Chinese immigrant workers. Much of the current Wawona Road follows the route of this original road. Despite the rough terrain, they completed the twenty-seven miles of road in only four and a half months! This bridge, no longer part of Wawona Road, was used by wagons, stages, and eventually cars as a vital link connecting Wawona and Yosemite Valley. All Yosemite-bound traffic through Wawona crossed the covered bridge. Today, buildings located near the covered bridge still represent some of the area's early activities and businesses. “The very instant the bridge is crossed on the way to the hotel, the whole place seems bristling with business, and business energy… horses are just being taken out, while others are being hitched up… freight wagons coming and going… stables for a hundred animals... blacksmiths’ shops, carriage and paint shops, laundries and other buildings.” James Hutchings, In the Heart of the Sierra, 1886

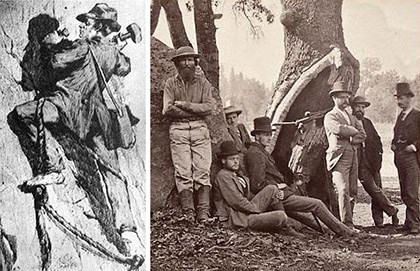

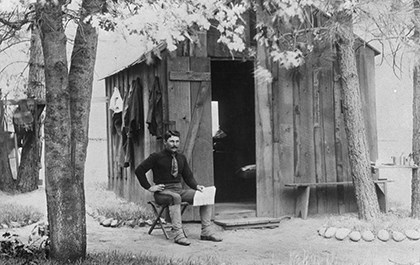

Anderson Cabin“Half Dome was perfectly inaccessible, being probably the only one of all the prominent points about Yosemite which has never been and will never be trodden by human foot.” Josiah Whitney, California State Geologist, 1869 George Anderson, a Scottish immigrant, came to Yosemite around 1868, working a variety of jobs to make ends meet in Yosemite Valley during the warm summer months. During the winter, Anderson lived in a modest cabin (pictured below), which was originally located in Big Meadow (now Foresta). Anderson applied his skills as a blacksmith and trail builder to open new pathways for sharing the beauties of Yosemite. His most daunting challenge was to find a way to the “perfectly inaccessible” summit of Half Dome, and through persistence, innovation, and guts, Anderson became the first known person known to have accomplished that feat. On that final steep slab of Half Dome, Anderson drilled holes and hammered in iron bolts of his own making, precariously standing on each bolt while painstakingly driving in the next. Shortly after his first ascent of Half Dome, Anderson began guiding others to the top. Besides creating this adventurous and popular hiking route up Half Dome, Anderson also built several other famous trails in Yosemite, including sections of the Mist Trail to Vernal and Nevada Fall.

Artist StudioLike many artists, Norwegian immigrant Chris Jorgensen fell in love with Yosemite’s grandeur, and challenged himself to capture it on canvas. After visiting Yosemite for the first time in 1898, Jorgensen was granted permission to build a home and a studio on the banks of the Merced River in Yosemite Valley (near today's Sentinel Bridge). From this summer home, Jorgensen produced paintings of his famous surroundings. For twenty years, he lived among the towering cliffs and waterfalls with his wife and fellow artist Angela. Chris Jorgensen often worked with watercolors, allowing for quick, spontaneous paintings to be completed in the field, rather than in the studio. He loved plein air painting, or painting outdoors. Beyond providing shade, the umbrella he holds in the image below helped with color perception in the harsh sunlight.

The bungalow in the Yosemite History Center, part of Jorgensen's Yosemite property, represents an era when artists were some of the best advocates for the preservation of wild places. Yosemite’s landscapes inspired artists to create, and as they shared their art with those unable to experience nature’s beauty first-hand, their creations inspired others to preserve Yosemite as a public park. Even today, Yosemite stirs visitors to connect creatively with the landscape. Photos, paintings, and written accounts of Yosemite are now more popular, and more shareable, than ever.

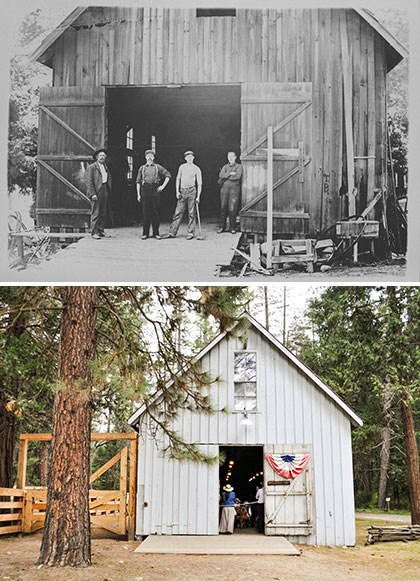

Gray BarnThe Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company was founded in 1877 under Henry Washburn, who also owned the Wawona Hotel. The operation was expansive, with eleven stages daily, delivering visitors to Yosemite Valley, Raymond, Glacier Point, and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. The company employed up to 40 stage drivers and kept 700 horses. Wawona was once the heart of a thriving transportation enterprise and was the largest stage stop in Yosemite. After hours of bouncing and bumping along uneven dirt roads, inbound stages stopped for the night at the Wawona Hotel before making the eight-hour trip to Yosemite Valley. If a stage needed a repair before the sixteen-hour roundtrip journey, Wawona was the place to visit. On site was a maintenance and repair facility to keep the stages in good condition and the horses properly shod. After cars were first allowed into Yosemite in 1913, the gray barn was a service station for autos, carrying on as a place to repair vehicles damaged by the park’s rough, winding roads.

Blacksmith ShopWith a piece of red-hot iron, a hammer and an anvil, a blacksmith could design and create nearly anything made of iron, crafting the tools and parts that kept communities moving. One of the primary duties of a Yosemite blacksmith was making wagon repairs. Blacksmith shops were located all along the Wawona Road to Yosemite Valley, each one ready to fix vehicles damaged by the rough roads. Early Yosemite tourists may never have completed the journey without the help of blacksmiths along the way. One such blacksmith who lived and worked in Yosemite was Fred Bruschi. Bruschi, born to Italian immigrants in the nearby town of Coulterville, began working as a park blacksmith around 1908. Fred worked in the park for 22 years, and even earned the local title “king of the anvil.” But Bruschi’s value to the community went beyond his skills with metalworking. Fred also forged fun social events for his Yosemite neighbors. He loved to dance the tango, played in a local band, and judged costume contests. Blacksmiths, once the lynchpin of Yosemite travel, still occasionally work in Yosemite to show their skills at the Blacksmith Shop in the Yosemite History Center (summer only). Homestead CabinThomas “Tom” Hodgdon acquired land for grazing cattle in Aspen Valley, now within Yosemite National Park. In 1879, Tom hired workers to build an access road, and a two-story cabin, on the land. To build the two-story log cabin, he hired a Chinese American cowboy named Ah Hoy and a neighbor named Franklin Babcock. There, Tom and family ran a ranching business, grazing cattle in nearby meadows. After these meadows became part of Yosemite National Park in 1890, U.S. Army troops enforced park regulations against grazing by dispersing cattle, and the Hodgdons lost grazing privileges. The family didn’t use the cabin for a while, and patrolling soldiers, and even Army horses, sheltered inside occasionally. No longer able to earn a living with livestock in Yosemite, the Hodgdon family adapted to make money from tourism. In 1882, as part of the Great Sierra Wagon Road, the Hodgdons’ access road was improved upon by Chinese workers, and extended to Tioga Pass for silver mining. When the Tioga Road opened to the public, tourist traffic increased through Aspen Valley. The Hodgdon family used their cabin, and created a complex of new buildings, used for tourist lodging. Eliza Hodgdon, Tom’s spouse, added to the entrepreneurial effort by selling hot meals to hungry travelers.

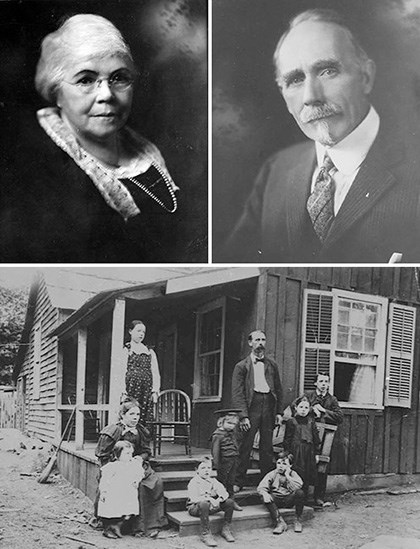

Degnan's BakeryIrish immigrants Bridget and John Degnan, along with their infant son Laurence, moved to Yosemite Valley in the mid-1880s. Mountain living proved tough at first. Thefamily first lived in an abandoned barn and had to carry household water from a nearby stream in a five-gallon oil can. Shortly after, they built their own house, which included plumbing. To support her growing family, Bridget began selling bread and baked goods from her home while raising eight children. With increasing numbers of tourists visiting Yosemite, Bridget helped meet food service demands by baking up to fifty loaves of bread a day in her small household oven. From her porch, she sold bread and home-cooked meals to Yosemite locals and toursits, each loaf selling for 12½ cents. Around 1898, the Degnans built a larger home and Bridget purchased a large brick commercial dutch oven for a more permanent bakery. She could then bake 400 loaves a day, and began serving full meals on her front porch to locals and park visitors. Her bakery (pictured below) was originally connected to their family home near the chapel in Yosemite Valley and is an important reminder of Yosemite's early visitor services. Bridget's legacy continued when her children opened an even bigger bakery in 1958, still open today as Degnan's Kitchen in Yosemite Village. It remained family-owned until 1972.

Powder HouseBefore the Wawona Road was finished in 1875, people could only access Yosemite Valley by foot or on horseback. It took the hard work of roadbuilders, including hundreds of Chinese American workers, to make it possible for stages, and later cars, to travel to Yosemite. Road-building in this region was not easy and explosives were needed to blast through the hard granite terrain to form roadbeds. The powder house, likely built by road worker and Irish immigrant John Degnan around 1880, was made to safely store explosive powder used in creating Yosemite’s roads and trails. The thick granite walls and sand-filled ceiling were built to contain an explosion resulting from accidental ignition of the explosives stored inside. In 1933, access to Yosemite Valley from Wawona was improved with the completion of the Wawona Tunnel. The tunnel’s power lines, its carbon monoxide sensors, and its high-speed fans made it an engineering feat. Workers used 275 tons of blasting powder and spent nearly two years drilling the tunnel at a rate of roughly 20 feet per day. Occasionally, the building was used as a jail, a very poor one. In 1915, two car thieves escaped by digging away the mortar between the rocks with a leg they twisted off the rickety steel-frame cot. The pair claimed the task was so easy that they waited until after breakfast to perform their escape.

Acting Superintendent's OfficeStarting in 1891, U.S. Army soldiers were among the first guardians of the recently established Yosemite National Park, protecting the park for twenty-three years before the creation of the National Park Service in 1916. The Army was well-suited for the work. Troops patrolled the park’s backcountry to ensure the land was protected from illegal grazing, poaching, and logging. Each summer, over 200 soldiers, usually cavalry, rode from the Presidio of San Francisco to protect both Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks. In 1899, 1903, and 1904, African-American buffalo soldiers also served in the Sierra Nevada. Yosemite encompasses vast areas of rugged, roadless terrain. To access such remote places for patrolling, Army officers trained in engineering at West Point supervised the construction of vital infrastructure such as roads, trails, and buildings. These challenging construction efforts gave birth to Yosemite’s backcountry trail system, used by hikers today. The Acting Superintendent’s Office was the headquarters for the Army officer in charge of Yosemite National Park. This building was originally constructed at Camp A.E. Wood, the present-day site of the Wawona Campground. Named after Captain Abram Epperson Wood, the first Army officer to serve as Acting Superintendent of Yosemite National Park, Camp A.E. Wood was the summer home for U.S. Army troops from 1891 through 1905. In 1906, the State of California returned Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the federal government to be managed as part of Yosemite National Park, and the headquarters moved to Yosemite Valley. Later this building was moved to the Yosemite History Center.

Ranger Patrol CabinAfter twenty-three years protecting the park, the U.S. Army was called away from Yosemite in 1914, and civilians began to assume ranger roles. It was the job of these rangers to protect the natural resources, stop forest fires, and assist visitors. Their duties were made more difficult as automobiles had recently been allowed to enter the park. The ranger patrol cabin (pictured below) was built in 1915 to house rangers at Crane Flat, a busy road junction. Buildings such as this were used as automobile check stations. Here drivers paid a fee to enter the park and were informed of regulations. At Crane Flat and others Yosemite locations, rangers needed to live close to backcountry patrol routes and roadside stations where they assisted visitors arriving by automobile. In 1916 the National Park Service was created and the rangers living here became some of the first National Park Service Rangers. Gabriel Sovulewski, a Polish immigrant, embodied the administrative transition from the military to the National Park Service in Yosemite. He first saw Yosemite in 1895 while on a summer deployment to the park with the U.S. Army. In 1902, he left the Army and returned to Yosemite to work as a packer and guide. In 1906, Gabriel was placed in charge of Yosemite National Park, serving as the top park official for thirty years. During that time he directed the construction of trails and buildings such as the Ranger Patrol Cabin. Gabriel Sovulewski remained in Yosemite for the rest of his life, and is buried next to his wife, Rose in the Yosemite Cemetery.

Yosemite Transportation OfficeThe Yosemite Transportation Office was constructed in Yosemite Valley in 1910 by the Yosemite Valley Railroad Company as a transportation terminal and telecommunications hub. Starting in 1907, Yosemite-bound tourists could ride the railroad from Merced to El Portal, just outside the park, eliminating the bumpy, dusty, two-day stage ride. However, the final fourteen-mile leg of the journey from El Portal to Yosemite Valley was still made by stage, and later by autos. Upon arrival at this terminal in Yosemite Valley, passengers could book a stay in a hotel and make transportation arrangements with travel agents, who lived in the building’s back rooms. Despite its rustic design, the office provided modern conveniences. Visitors could make telephone calls or send telegrams to anywhere in the world. By 1914, automobiles were common in Yosemite, and in that year, horse-drawn stage service was discontinued. However, annual visitation to the park in 1915 doubled to 31,000. Consequently, stage operation was renewed but only for one additional year. The reliance on transportation companies for park access diminished greatly when the All-Year Highway (now California Highway 140) opened in 1927, and personal cars soon became the dominant means of transportation in Yosemite.

Chinese LaundryThe Chinese Laundry building was constructed in Wawona in 1917 to serve as a laundry for the Wawona Hotel, replacing a previous, smaller laundry building. While the building was new, the workers weren't: Chinese immigrants Ah Yee and Ah Wee had worked at the Wawona Hotel for years prior and continued their washing and ironing in the new laundry. From 1918 to 1933, these two men, and other Chinese immigrants, worked in this building to clean linens, towels, and clothing for guests. During busy summer months, four to five hotel employees heated water on wood burning stoves, stirred steaming pots of laundry with paddles, and pressed sheets and garments flat with irons also heated on wood stoves. Chinese people immigrated to California during the Gold Rush, but by 1850 the Foreign Miners Tax forced many Chinese to search for work outside the mines. Resilient and skilled, they soon found work, and a home, in Yosemite. Here, Chinese workers provided essential services in laundries, kitchens, and on road crews. This building is open to visitors from late spring through early fall.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Park Ranger Yenyen Chan shares the history of the Chinese Laundry building located in Wawona, along with information and artifacts uncovered that have taught us more about the role Chinese played in Yosemite's history. |

Last updated: October 25, 2022