Photos: "History of the United States Naval Special Hospital: Yosemite National Park" Yosemite’s luxurious Ahwahnee was the brainchild of the National Park Service’s first director, Stephen Mather. Almost from the first moment he saw Yosemite Valley, Mather envisioned building a luxury resort hotel to attract the wealthy visitors. Mather hoped that by experiencing the park, these well-to-do visitors would be interested in protecting the park and financing developments that would benefit all visitors. He dedicated his political expertise and personal financial resources to making the scheme a reality.

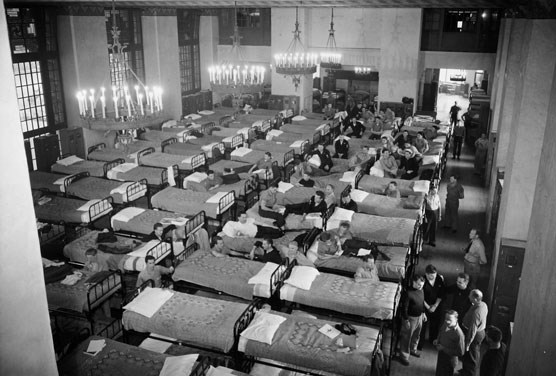

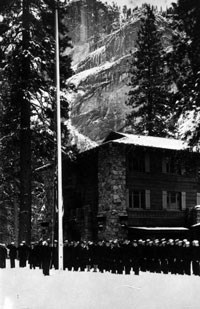

The Ahwahnee did not attract many guests immediately. The Yosemite Park and Curry Company (YPCC) began lobbying the National Park Service for self-contained recreational facilities at the hotel: a dance pavilion, golf course, swimming pool, tennis and croquet courts, a “Kiddie Kamp,” and “the building of bridle paths and foot paths.” By 1930, the golf course and tennis/croquet courts had been added. In spite of these additions, The Ahwahnee continued to struggle. The Great Depression greatly reduced visitation to Yosemite, and its new luxury hotel operation was hit especially hard. Although tourism gradually began to improve after 1939, the outbreak of WWII in 1941 proved to be disastrous for many of YPCC's operations. Fuel rationing sent automobile traffic and visitation spiraling downward once again. The Wawona Hotel was closed, and the Glacier Point Hotel severely curtailed its services. The Ahwahnee, which had been barely profitable even in the best of times, had difficulty keeping its doors open. However, World War II saved The Ahwahnee from its financial struggles. The Department of the Navy offered a long-term arrangement to rent the entire hotel. Well before Pearl Harbor, the Navy had anticipated a drastic need for increased medical treatment facilities if, or when, the country went to war. The Ahwahnee was one of several sites the Navy surveyed in the summer of 1941 as possible candidates for emergency conversion to wartime hospitals. In 1943, the Navy leased The Ahwahnee for that purpose with the first staff arriving at the end of May to begin refitting. The transition was not easy, partly because visitors were still being lodged at the facility when the Navy arrived. The “U.S. Naval Convalescent Hospital Yosemite National Park, California” was commissioned on June 25, 1943. Eleven days later, the first patients arrived.

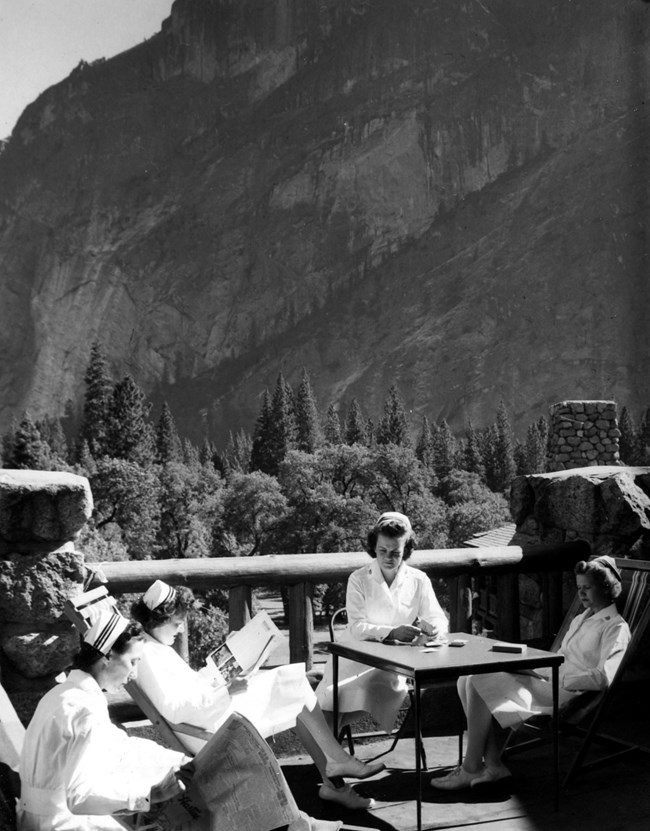

The Navy’s operation at Yosemite was initially intended for neuro-psychiatric rehabilitation. The thinking was that "shell-shocked" patients would respond well to the peaceful setting of an isolated scenic facility. In fact, the site quickly proved to be exactly the opposite of what these patients needed. The towering cliffs caused many to become claustrophobic. Isolation and lack of diversionary social or entertainment often left them preoccupied with the very memories the Navy hoped to erase. Within a few months, hospital administrators decided to phase out psychiatric treatment at the Ahwahnee and convert the facility into a general physical rehab unit. It was a new direction, but the same problems prevailed. As one early staff member recalled, “If the patients weren’t nuts when they got to Yosemite, the boredom there soon sent them over the edge.” Staff morale also suffered badly. In August 1943, A change in Navy leadership marked a dramatic change in the hospital’s rehabilitation strategies. The new commander, Captain Reynolds Hayden, was a seasoned veteran with years of experience managing military medical units (including as commanding officer of the Navy Hospital at Pearl Harbor during the 1941 surprise attack). Besides being an inspirational leader, Hayden was competent, sensible, compassionate, and very resourceful. He immediately began aggressively expanding the hospital’s recreational and rehabilitation resources. Simultaneously, the National Park Service and a number of local and regional civic organizations also began improving the plight of the staff and patients stationed at Yosemite. By successfully scrounging, begging, borrowing, and politicking, Hayden’s administration expanded hospital facilities to include a library, a six-lane bowling alley, an extensive crafts department, a pool hall, daily excursions to Badger Pass during the winter (with free equipment and mandatory lessons from a staff trainer), re-opening of the Camp Curry toboggan run (operated by Navy staff), on-site publication of the hospital’s own newspaper, a Ship’s Service store (including a soda fountain), a Welfare Fund, machine and wood shops, and transportation facilities.An adjustment of Navy regulations allowed patients and staff to take leave outside the park. Additional hospital improvements included tripling the hospital’s physiotherapy facilities and equipment, significantly improving available housing for families of patients and staff, forming a staff/patient dance band at the hospital, organizing regular guest appearances by orchestras and USO entertainers, acquiring a projector and screen to show Hollywood movies on a regular basis, constructing new concrete tennis and basketball courts, and, last but not least, building the servicemen’s own “Oasis” beer joint, the only authorized pub in any Naval hospital around the world. By the time the hospital was decommissioned in December 1945, rehabilitation at Yosemite’s newly renamed “Special” Hospital had dramatically changed from what the first patients experienced a year and a half earlier. Priorities for treatment shifted from simply warehousing and physically fixing up patients to a more holistic approach of healing them body and soul. Administrators realized that treatment needed to include mainstreaming patients back into a non-military social environment, rather than isolating them from it. Because it was impossible to move the hospital to a “normal” community social setting, Captain Reynolds decided to create a community at Yosemite for the patients and staff. All he had to do was provide the housing, recreational facilities, and activities; the social interaction they fostered would do the community-building for him. And, of course, success was due in a large part to the outlying communities bringing themselves to the hospital. It was a remarkable learning experience for the hospital’s staff and administrators. The Yosemite Special Hospital experiment proved to be a watershed event in the development of U.S. military medical rehabilitation techniques.

|

Last updated: July 15, 2019