"On a global basis…the two great destroyers of biodiversity are, first habitat destruction and, second, invasion by exotic species." - E.O. Wilson, Harvard ecologist Yosemite National Park, from its minute wildflowers to its towering giant sequoias, is a place of contrasting beauty with nearly intact natural diversity. The park's 11,000-foot elevation range provides a phenomenal variety of growing conditions and habitat for more than 1,450 native plant species to thrive. In spring and summer, Yosemite's wildflowers erupt in profuse and spectacular displays, supplying food, habitat and shelter for a great variety of wildlife.

Invasive plants are the largest threat to biodiversity within Yosemite. Currently, 275 non-native plant species have been documented within the park, 28 of which have been discovered since 2012. Many of Yosemite's four million annual visitors cross through weed-infested lands on their way here; unintentionally bringing invasive plant seeds in on socks, shoe laces, vehicle tires, and pet fur. Invasive plants are also unintentionally brought in by park management through construction projects, and maintenance or stock use. Keeping weeds out of Yosemite is a continuous challenge that requires a comprehensive understanding of invasive plant biology, threats, and treatments balanced with an appreciation for the logistics posed by such a large and rugged park. Not all non-native plants are considered invasive; the large majority of Yosemite's exotic plants pose little threat to native plant communities. To be considered invasive, a species must demonstrate the ability to rapidly displace native plants, alter fire regimes, or significantly alter ecosystem structure or function. Because of the complex ecological relationships among native organisms, impacts to native plant communities can negatively affect associated wildlife throughout Yosemite. Invasive plants are prioritized for control based upon the threat they pose to the ecosystem they inhabit and the park's capabilities for successful control. The invasive plants that Yosemite currently considers a high-priority for treatment are: yellow star-thistle, Himalayan blackberry, common velvet grass, Italian thistle, spotted knapweed, rush skeletonweed, Medusahead, and jointed goatgrass. Additionally, any newly discovered non-native plants are considered a high priority since eradication can be achieved before an infestation can establish and significant ecological damage occurs. How do Invasive Plants Get Here?

ClothingMuch like the fur of an animal, seeds can get stuck in our clothing and then be transported to new locations. ConstructionEquipment and construction materials can harbor propagules of invasive species. Ground disturbance by heavy equipment, whether it is to improve facilities or repair roads, creates optimal soil conditions for plants to become established. Escaped OrnamentalsSome beloved garden plants have escaped cultivation and wreak havoc on natural ecosystems. Many horticultural plants have this potential, be aware about what you introduce to your garden and surrounding environment. StockHorses or mules can easily spread invasives from their fur or feces if they have been in weed infested areas or have been eating feed that has invasive plant seeds in it. Yosemite encourages the use of weed-free forage in order to mitigate this threat. VehiclesNew weeds are often found along roadsides. Mud and dirt caked onto your car or tires can contain invasive plant seeds. A quick car wash could prevent Yosemite's next invasive plant. WildlifeSome invasive plants like Himalayan blackberry have seeds encased in fruit that are a favorite food for bears, birds, and other wildlife. These animals can easily spread invasive plants from their fur or feces. Wind/WaterSome seeds can be transported great distances by natural forces of wind and water. How do Invasive Plants Impact Yosemite?Invasive species not only displace native plants, they also have severe negative impacts on many other cultural and natural features. Impact Native WildlifeNative plants and wildlife depend on each other for their survival and well-being. Many native animals, particularly insects, are highly specialized in their food source and habitat, so a disruption in the distribution or availability of a certain plant or community could be devastating. Some non-native plants can provide unnatural food abundance, affecting the distribution and behavior of animals. For example, non-native blackberry, at the peak of its infestation, covered about 80 acres of Yosemite Valley, often near developed areas. Ripe blackberries attract black bears to those developed areas, which increases the frequency of human-bear interactions, and can compromise the safety of both wildlife and visitors. Change Fire RegimesInvasive species such as cheat grass can alter the frequency, seasonality, and intensity of fires. Changes to the fire regime fundamentally alters habitat, displacing plants and animals. Alter the Visitor ExperienceInvasive plants can transform spectacular displays of showy wildflowers into large, unattractive monocultures. Thorns and spines on invasives can turn inviting and accessible areas into impassable and unattractive thickets of brambles. Cause Impacts Beyond Park BordersInvasive species have no regard for political boundaries. They can rapidly spread between Yosemite and adjacent lands. The Long Battle Against Invasive Plants

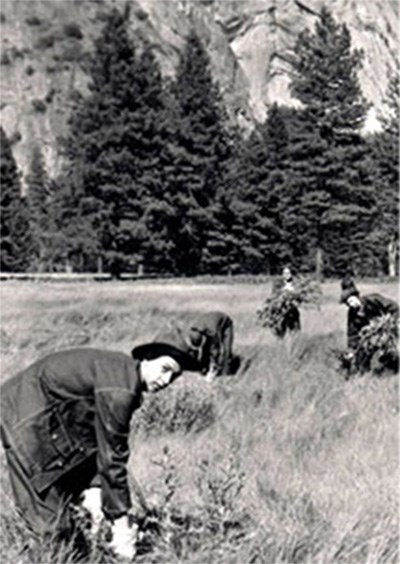

Yosemite's understanding of the science of invasive plants has come a long way since the 1930s, when Civilian Conservation Corps workers began pulling bull thistle, common mullein, and Klamath weed in Yosemite Valley. After 80 years of diverse management tactics, these invasive species are still widespread. A wide range of tools, skills, sophisticated technology, financial resources, and detailed planning systems are needed to ensure a robust and effective invasive plant management program. Today, Yosemite's Invasive Plant Management Program is based upon the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM)—a time-tested, decision-making process that follows the best available science and practical experience that involves inventory, prioritization, prevention, control, treatment, monitoring, research, and outreach. IPM ensures the most effective tools and methods are used to protect the park's resources and have minimal impact upon people and the environment. Invasive plant control actions are an often expensive and time-consuming response to a problem that could have been prevented or detected early and eradicated. Yosemite's invasive plant management program ensures the protection of all the park's diverse natural and cultural resources through a collaborative process. This process begins each winter with consultations between management staff and resource professionals, including park botanists, wildlife biologists, and anthropologists. Each year the park shares its annual work plan, and reaches out to American Indian tribes and the general public for feedback. Annual work plans are posted online, with the public encouraged to comment. An informed and open dialogue is a significant asset to the protection of park resources from the spread of invasive plants. The park's management of invasive plants incorporates the following goals:

Yosemite's Invasive Plant Management Plan and Annual Work Plan

Yosemite's High Priority WeedYellow star-thistle, one of Yosemite's most aggressive invasive plants, tells a challenging management story. Already widespread throughout California, yellow star-thistle has become well established in the Sierra Nevada foothills relatively recently. Along the steep river canyons of the park's western boundary, land managers are trying to stop its eastward spread. In previous years, the invasive plant program has used mechanical mowing as a means of control with moderate success. However, due to the large scale and complex steep terrain of the infestation, herbicide treatment is the only reasonable option for safe and successful large-scale control in the Merced River Canyon. Because of the high rate of efficacy of chemical treatments, the yellow star-thistle infestation has reduced drastically. With successful treatments, both the areas of infestation and the amount of herbicide needed for follow up treatments are drastically reduced. Learn more about Invasive Plants

|

Last updated: November 18, 2024