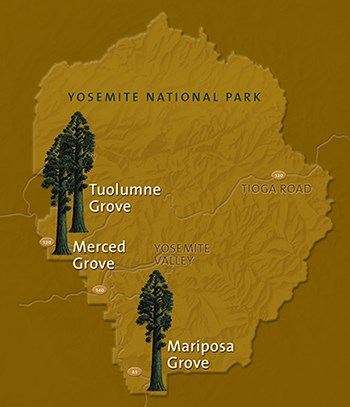

Yosemite National Park's massive giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum) live in three groves in the park. The most easily accessible of these is the Mariposa Grove near the park's South Entrance. Two smaller—and less visited—groves are the Tuolumne and Merced Groves near Crane Flat. With necks craning to see these tall trees, visitors often ask: "How old is that tree?" Just how long can certain Yosemite tree species live? Whitebark pine, Western juniper and Douglas-fir can live more than 1,000 years while giant sequoias can live more than 3,000 years. Giant sequoias are the third longest-lived tree species with the oldest known specimen to have been 3,266 years old in the Converse Basin Grove of Giant Sequoia National Monument. Giant sequoias are only outlived by bristlecone pines (oldest age recorded at 4,844 years in the Great Basin) and by Alerce trees (oldest age recorded at 3,639 years in Chile). Yosemite’s famous Grizzly Giant in the Mariposa Grove is estimated to be about 3,000 years old plus or minus a few centuries, which is nothing to a giant sequoia.

Scientists currently rank the Grizzy Giant's large size, or volume, as No. 25. The largest sequoia by volume is the General Sherman tree in Sequoia National Park. These large giant sequoias often owe their size to rapid growth rather than age, so an old giant sequoia will not necessarily be the largest specimen. The study of visitor use impacts on sequoias, particularly compaction and erosion of soils near the base of the trees due to trampling, has long concerned ecologists. In 1962, a University of Michigan academic assessed human impacts on the Mariposa Grove to inform park management. Twenty-first century scientists applaud this early recognition to study and to measure how human's actions might prove detrimental to the giant sequoia's health and vigor. Mariposa Grove RestorationThe large Sierra snowpack provides much needed moisture to the trees as it slowly melts during the spring. Sequoias have a relatively shallow but extensive root system, reaching to over a hundred feet in all directions from their base. These roots capture the groundwater which allows the trees to survive the long, hot summers of Yosemite; a healthy root structure is essential to ensure their longevity. The Mariposa Grove reopened in June, 2018, after being closed three years for restoration. The two primary goals of this project were to improve giant sequoia habitat and visitor experience. This included addressing the declining conditions of the Grove and nearby South Entrance that were adversely affecting the ecological health of the sequoias (e.g., roads, trails and other buildings encroaching on roots of the ancient trees, hydrology issues). Crews improved habitat for sequoias by removing parking lots and roads, and restoring the natural flow of water to the trees. Parking was relocated two miles away from the grove, and is connected by shuttle buses. The restoration also added accessible trails and improved bathrooms. This was the largest restoration project in the history of the park. Giant Sequoias and FireNaturally occurring fire by lightning would have historically occurred in Yosemite's sequoia groves frequently, burning the areas with lower intensity surface fires. Therefore, large giant sequoias are adapted to survive repeated fires. They have a thick, fibrous bark that insulates them from the heat of a fire. Additionally, sequoias tend to drop their lower branches as they grow taller and older which helps avoid fire from climbing up to the tops of the trees into the canopy. Fire is also essential in helping sequoias with seed dispersal. The heat from a fire in a sequoia grove helps to dry out the older cones high in the tree. Once open, the seeds flutter down to the new perfectly bare soil that fire has just made available. Giant sequoias need abundant sunshine, so after a fire travels through a sequoia grove, clearing out dead and downed wood and smaller trees, it leaves behind sunny gaps for these new seeds to grow. For centuries, American Indians introduced fire to create better hunting, grazing, and living conditions. Many of the beautiful and productive forests that greeted early European-American settlers in the area were actually crafted by American Indians through manipulation by fire. American Indians have understood the beneficial and natural role fire plays in ecosystems for thousands of years. Upon the arrival of European-Americans and early park managers, it was largely believed that fires were destructive and sequoia groves in particular should be protected from fire. Fire suppression was the primary management tool from the 1860s through the 1960s. During that 100 year period, forests throughout the Sierra Nevada grew thick with trees, shrubs, and dead and down material. These dense forests had essentially become a fire hazard and had halted many of the natural processes that help keep an ecosystem thriving. Beginning in the late 1960s, fire ecologists realized this and worked to change how forests in this region of the Sierra Nevada were managed. Beginning in 1970, Yosemite and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks introduced prescribed burning as a management tool to bring about the change in an ecosystem that mimics the effects of lightning ignited wildfire. Prescribed burns are small fires that are purposely set under highly regulated conditions and managed within a planned, geographic area. Today, prescribed burning is still an essental part of how we manage sequoia groves in the park. ArticlesVideos

|

Last updated: July 27, 2023