|

The Nuʻu Section of Haleakalā National Park was purchased in 2008. The parcel is comprised of over 4,100 acres and extends from the southern rim of Haleakalā to the coast where Hāwelewele Gulch meets the ocean near Nuʻu Bay. The area remains closed to the public while exclosure fencing is installed to fence out feral animals and support NPS efforts to restore native plants and wildlife in the upland portions of the parcel. Archeologists have surveyed around 250 acres of the parcel, which is rich in history and culture. For now, we invite you to read up on this remarkable area!

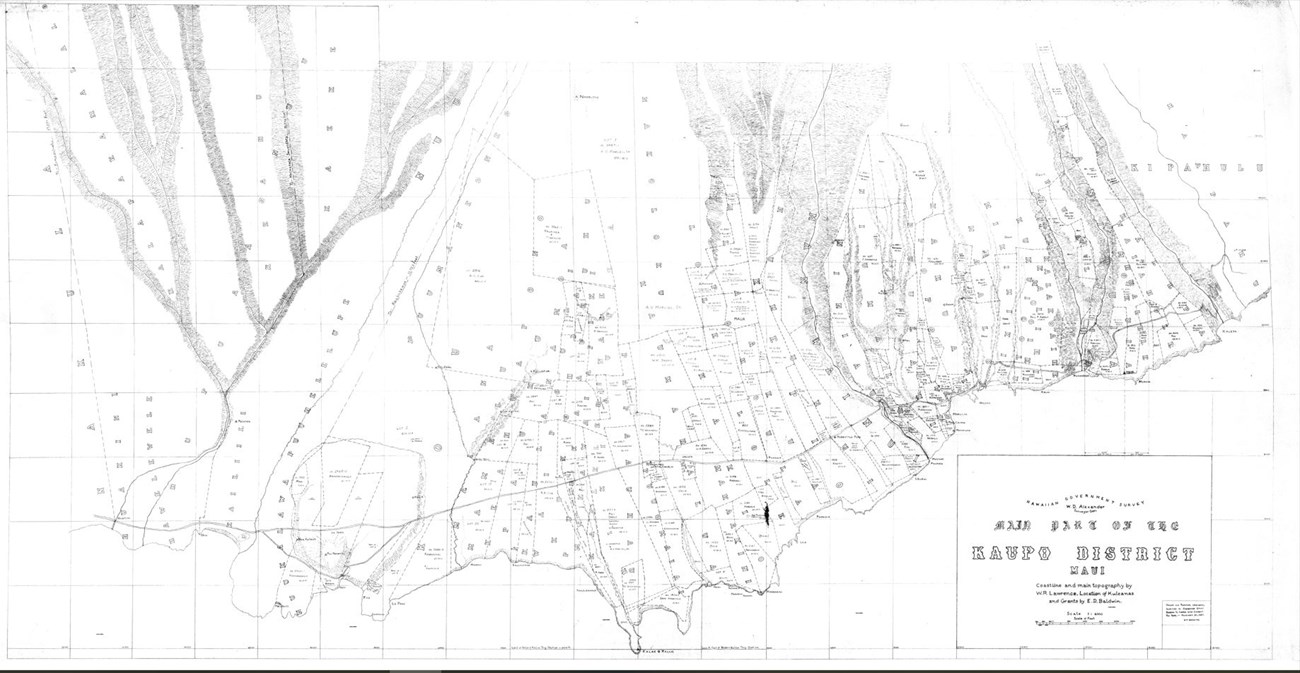

The Alexander Map of 1885 Haleakalā National Park acquired the Nuʻu parcel from the James Campbell Company with the support of The Conservation Fund and appropriations from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Next door is the Hawaiʻi Land Trust (HILT) parcel at Nuʻu Bay. The two areas are only separated by modern land boundaries. HILT acquired its 80 coastal acres from Kaupo Ranch in 2011. After initial archeological survey, one of the recommendations is to consider collaborating with adjacent landowners (private/HILT/NPS) to nominate Nu‘u Village to the National Register of Historic Places as a Historic District. National Register eligibility and listing aligns with the National Park Service mission to “preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.”

IARII Photo Radiocarbon dating suggests that initial use of the area took place no later than the 1400s-1600s. Kaupō Moku was famous for its sweet potatoes thanks to the rich volcanic soil of its ahupuaʻa. The district was a center of activity on Maui during Native Hawaiian Pre-Contact times:

Nuʻu Ahupuaʻa was a relatively massive ahupuaʻa within the moku of Kaupō. Historians believe it may in fact have been an ʻokana (district or subdistrict) made up of many smaller ahupuaʻa (Walmisley 2021). Nuʻu is in the far western, dryer portion of Kaupō moku, yet archeological evidence and written records demonstrate it was a productive and well-populated place.

NPS Photo The rainfed dryland field systems that are found in Nuʻu are extensive likely because the Native Hawaiians used a generalized 4-10 system of farming. Native Hawaiians would cultivate ʻuala (sweet potatoes) in a field for 4 years and allow for a 10-year period of fallow. Oftentimes, kō (sugarcane), which is rich in nutrients and adds nitrogen back into the soil, was planted as a hedge on the borders of these productive fields (Handy and Handy 1941, 186). The area is also known for its heiau (temples). Anthropologist Patrick Kirch and archaeoastronomer Clive Ruggles conducted an analysis of 78 heiau throughout Kahikinui and Kaupō, finding a large variety of temple form and function, and relating the temple orientation to the Hawaiian gods and Hawaiian seasons and rituals. For example, in the moku of Kaupō, the heiau called Loʻaloʻa:

The rich agricultural opportunities and increasingly powerful aliʻi (chiefs) of the 1600s contributed to the population growth and construction of structures in Kaupō Moku. In the 1700s, King Kekaulike, the mōʻī (king) of Maui, had built his royal center at the eastern end of Kaupō, at Mokulau, and as many as 17,500 people lived in the district (Kamakau 1996; Kirch, Holson, and Baer 2010; cited in Walmisley 2021). It was also told that Kekaulike had a residence at Nuʻu, where he was said to farm and fish with his people. His son was later born at Nuʻu (Walmisley 2021).

Record: OHA-Kipuka Database 6239 Post-Contact times Written records from nā nūpepa (Hawaiian language newspapers) and many other sources confirm that Nuʻu was a thriving center of Native Hawaiian population well into the 19th century. Many notable Native Hawaiians lived at Nuʻu during the 19th century, including Elia Helekūnihi, a descendant of “lesser aliʻi (chiefs),” a Lahaināluna graduate, teacher, pastor and leader who was born and lived on what is now the coastal portion of the Nuʻu parcel.

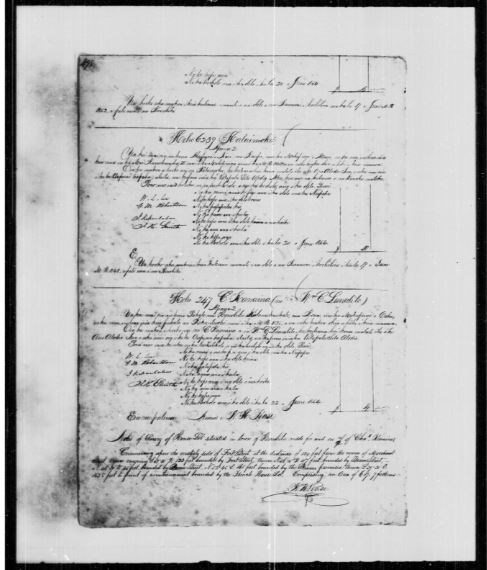

NPS Photo By the close of the 19th century, James Campbell had acquired half of the Nuʻu Ahupuaʻa (The Daily Bulletin 1892). James Campbell was an Irish immigrant who arrived in Hawaiʻi in 1850 at the age of 24 on a whaling ship after surviving a shipwreck in the Tuamotus. As sugar production increased in Hawaiʻi, Campbell became involved in sugar cane processing and became one of the largest landowners in the Hawaiian Islands. Campbell was one of the three founders of Pioneer Mill in Lahaina on Maui. He married Abigail Kuaihelani Maipinepine, who came from a line of Hawaiian aliʻi. Their daughter, Abigail, married Kawānanakoa, the hanai (adopted) son of Queen Kapiʻolani, and became Princess Abigail Kawānanakoa. On February 13th, 1892, Campbell purchased one-half of the Ahupuaʻa of Nuʻu from the estate of Kalākaua at auction for $4,600 (The Daily Bulletin 1892). After Campbell’s death, the land was amalgamated into the Campbell Trust which later became the James Campbell Company.

One of the many remaining post-Contact structures at Nuʻu is that of the old stone church complex. It is very likely that the “hale pule kahiko” (a name for the church given on an 1878 map) may be one of several Catholic chapels that were built along the Maui coast from Kahikinui to Keʻanae. The church was served by Father Modeste Favens, who baptized hundreds of Native Hawaiians on his arrival in Kaupō in 1846 (Walmisley 2021). These converts had come to Catholicism well before the arrival of a foreign priest, through the efforts of other Native Hawaiians.

NPS Photo Preservation Mahalo for stopping by to learn about Nuʻu and Kaupō Moku! Stay up to date about this area on East Maui Press! Remember to please respect the kapu (closure) of the area to help ensure that documentation and preservation can be completed. Whenever you find yourself near archeological sites, always remember to leave things be, and Leave No Trace! We hope to be able to share more about this amazing area with our visitors both virtually and on island in the future!

References: Baer, Alexander. “Ceremonial architecture and the spatial proscription of community: location versus form and function in Kaupō, Maui, Hawaiian Islands.” Journal of the Polynesian Society 125, no. 3 (September 2016): 289-305. http//dx.doi.org/10.15286/jps.125.3.289-305. Handy, E. S. Craighill and Elizabeth G. Handy. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore and Environment. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, Revised Edition 1991. Kirch, Patrick V. and Clive Ruggles. Heiau ‘Āina Lani: The Hawaiian Temple System in Ancient Kahikinui and Kaupō, Maui. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2019. McGregor, Davianna P. Nā Kua‘āina: Living Hawaiian Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2007. Walmisley, Andrew J. The Betrayal of Elia Helekūnihi, The Politics of Tradition and Colonisation by Stealth in Nineteenth Century Hawaiʻi. PhD diss. University of Birmingham, 2021.

|

Last updated: October 15, 2024