|

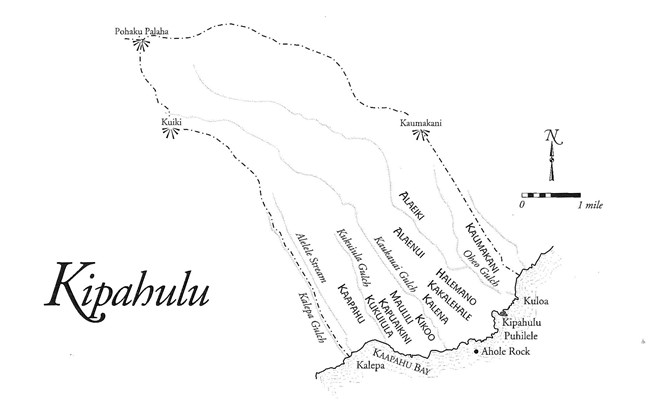

Kīpahulu was once composed of thriving settlements along the coast, and the place of great battles between the chiefs of Maui and the chiefs of Hawaiʻi island, who often controlled East Maui. Kīpahulu has had many layers of occupation since it was first settled by Polynesian voyagers. Throughout all of the changes, Kīpahulu has remained an important moku in East Maui. From mauka to makai Kīpahulu is fertile with good land for growing kalo as well as plentiful other fruits and vegatables, fresh water streams, and plentiful marine resources.

NPS Graphic

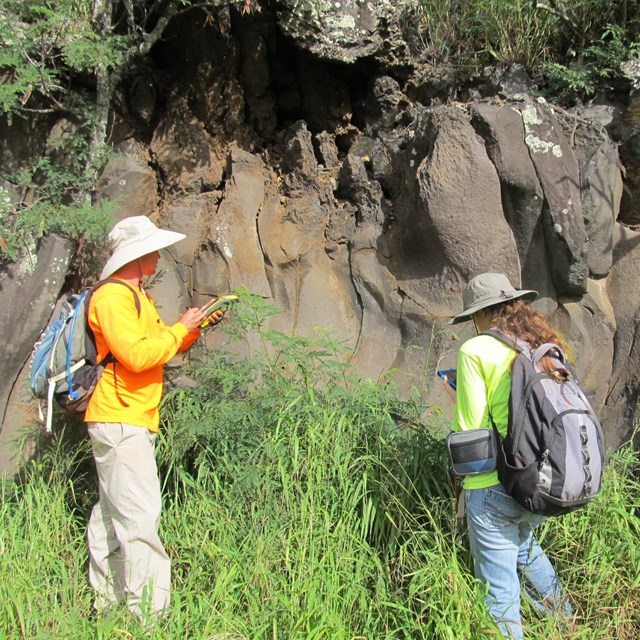

NPS Photo Archeological Sites in Kīpahulu:

The Kīpahulu coastal settlements consisted of unirrigated rain-fed gardens that supported traditional Hawaiian staple vegetables of kalo (taro) and ʻuala (sweet potato), among numerous other crops. The area has an abundance of marine resources, and fishers used various hooks and lines to capture primarily benthic and pelagic fishes. The marine technology associated with this method of fishing included a variety of rotating and jabbing fishhooks, along with trolling lures and points.

Along the Kūloa Point and Pīpīwai Trails you can see evidence of the Kīpahulu coastal village as well as evidence of each layer of human occupation:

"Sites of Maui" by Elspeth P. Sterling, published in Honolulu in 1998 by Bishop Museum Press. Further inland in the forested region and along NPS trails are plentiful loʻi kalo (irrigated taro terraces), animal enclosures or garden walls, and house sites. Combined, these sites help Haleakalā National Park to understand how populous Kīpahulu was before it was impacted by Western contact, development and disease. La Perouse, who did not land in Kīpahulu but sailed past in 1786, stated in the first written description of Kīpahulu, “I coasted along its shore at a distance of a league (2.5 miles)...we beheld water falling in cascades...the inhabitants, which are so numerous that a space of 3-4 leagues may be taken for a single village. The huts are on the coast so that the habitable part of the island is less than half a league.”

NPS Photo The Kīpahulu ʻOhana has done the laborious and important work of restoring ancient loʻi kalo at Kapahu Living Farm, in the Kīpahulu District. As part of their work restoring the moku of Kīpahulu, they cultivate kalo for the wider Kīpahulu and Hāna community and educate the community on traditional subsistence practices from mauka to makai. Former Superintendent Don Reeser was instrumental in forming the cooperative agreement between the park and the Kīpahulu ʻOhana.

|

Last updated: November 30, 2022