By Stephen Canright, former Curator of Maritime HistoryDuring the summer of 2013, San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park (NHP) assisted with the remarkable recovery of an intact Gold Rush-era cargo lighter, discovered during a construction excavation at the corner of Folsom and Main streets. During a brief period in the mid-1800s, these small barges transported people and goods to shore from larger ships before any piers existed in deep water. Likely, two men rowed a lighter, with each standing up and facing forward at midship while holding an oar. Lighters could also be towed or, in shallow water, steered by poles.

Photo courtesy © William Self Associates First ContactStaff at SF Maritime NHP first heard about the lighter in an e-mail sent by former Maritime Ranger Gary Keep to then-Park Superintendent Craig Kenkel on July 22, 2013. Gary attached several photos and suggested that the piece looked like a scow lighter. Kenkel forwarded the message around, asking if anyone knew anything about it. No one did. The next morning, I received a call from Bill Self of William Self and Associates, the consulting archaeologists on site, inviting me to take a look. He noted that his call was at the suggestion of Allison Vanderslice of the City Planning Department, who park staff had met on past projects, including the Candace site dig and work at Pier 70. Bill asked if the park might be interested in adding the boat to our museum collections. I immediately hurried over to check out the discovery. The Charles Hare SiteWhen I arrived, the lighter had been largely uncovered and its interior mostly cleaned of sand. The William Self and Associates crew, comprising 25 members, had been working for nearly a month under their project manager Amiee Arrigoni. The crew anticipated finding marine materials at the site, a continuation of the Charles Hare ship-breaking yard where ships were dismantled between about 1852 and 1857. SF Maritime NHP had accepted other archaeological items, including ship timbers, from previous excavations. The current site, like the prior one that had yielded the timbers, was being excavated for condominium tower development by Tishman-Speyer. When I first saw the boat, the site had been dug to about 15 feet below grade, a level just short of the old Bay bottom. The archeological crew scrambled to record the miscellany of ship timbers and yard structures they found, and I watched as they carefully sorted through mounds of material. Strewn across the site were ships' knees and futtocks, the remains of the grid-work and drain structures that had been built for the yard, and finally, a more-or-less intact boat.

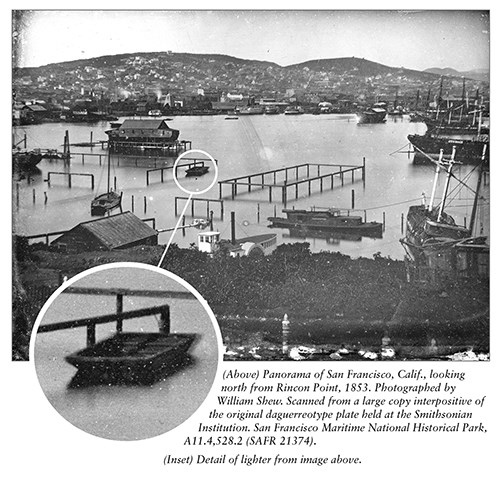

NPS Photo, A11.4, 528.2 (SAFR 21374). The Nature of the BoatSand was still banked firmly around the lighter's hull, helping to hold it together. The hull, spanned by one deck beam well aft of midship, remained intact. Overall, the boat is roughly 23 ft. long by 9 ft. wide by 3 ft. deep. I immediately confirmed that it was a lighter —Gary had been right. We recognized these little barges from panoramic photographs of Yerba Buena Cove in the 1850s, showing its shallow waters filled with ships in various states of abandonment. The lighters were used during a brief period from 1849 to 1854 as the only means to carry people or goods ashore, and the several dozen lighters in operation would have been much in demand. As privately built piers jutted into deeper water to accommodate large ships, the utility of lighters diminished, rendering them obsolete by the mid-1850s. From subsequent laboratory testing, we found that the Hare lighter was built from a species of beech native to Chile and parts of Argentina. In the earliest days of the Gold Rush, Chilean entrepreneurs owned many of the storage ships and early port infrastructure. The boat was almost certainly shipped from Chile to be nailed together on the muddy shoreline of Yerba Buena Cove. The Boat Fills with WaterWhen we first saw the boat, a small sump pump was set up in the northern or port side bilge to control a persistent inflow of water through the port chine seam. We initially assumed salt water was flowing into the excavation site with the rising tide. Two days later, our intrepid Museum Technician Eloise Warren was moved to taste this water, which certainly looked clear and clean enough. She found it to be fresh water, which I also tasted and confirmed. The lack of fresh water was a persistent problem in Gold Rush San Francisco. No streams ran through the sand dunes to the original town site, the closest streams being Mission Creek or one of two streams in the Presidio. When the ship Niantic was run ashore at Yerba Buena Cove in 1849, her pump well pipe was driven, apparently by chance, into an artesian spring source. This became a big deal, and the owners made good money selling fresh water by the gallon. The Charles Hare lighter was sitting on top of another artesian spring that came bubbling up through the chine seam and collected inside the hull. This had to be more than coincidence. The boat was fixed firmly in place by six posts, two of which were spiked into the hull. She was not meant to move, and as she lay alongside the grid-work platform of the wrecking yard, she filled with valuable fresh water. That water would have been useful in watering horses and likely provided water for people as well, including the Chinese fishermen who formed the labor crews at the Hare Yard. This secondary use of the hull may account for the survival of the boat, which became part of the larger structure and was somewhat protected as fill covered the whole yard.

NPS Photo/Dave Casebolt Deciding to Take in the LighterOn my first visit, I decided to see if it might be possible for SF Maritime NHP to take on the boat. The lighter seemed just small enough and in sound enough condition to make this proposition possible. The value of the find seemed to be self-evident. The boat could only date from 1849 or the early 1850s, making it among the earliest surviving boats in the entire U.S. Older large vessels, or at least fragments of those vessels, existed, but few small boats. I indicated to Bill Self and Amiee Arrigoni that we were very interested in the boat. I recommended that it be kept as wet as possible and covered with a tarp or a sheet of plastic to slow down the drying process. The next day, I returned with Bill Doll, our Preservation Department Manager. We met Carl D. Shannon, Senior Managing Director of Tishman-Speyer, and Sandy Reek, their Project Manager. Reek became our main contact on arrangements for the lighter, and Tishman-Speyer offered to underwrite all costs for building a cradle and moving the boat to our site. We also met Mike McGuire, the site boss for Lend-Lease, the master contractor on the construction site. The removal of the boat would have to wait for additional work on the larger site, notably the installation of I-beam piers around the excavation's perimeter for stabilization. We returned the next day with Eloise Warren and Dave Casebolt, our Conservator. We had already secured the conceptual approval to acquire the piece from Superintendent Kenkel, who had a background in historical architecture and was quick to see the lighter's value. Waiting and PlanningAn agreement signed on August 1, 2013, transferred the boat to National Park Service ownership. Tishman-Speyer agreed to contribute $3,000 for its conservation treatment and to make all arrangements for removal. They contracted with Sheedy Drayage, a respected local rigging firm, to build a cradle, make the lift, and deliver the piece to our new warehouse in San Leandro. Sheedy Drayage proposed a structure based on two 8-inch I-beams running fore-and-aft, spanned by seven 6-inch I-beams running athwartships under the boat. The structure would be welded together to form a rigid platform and the hull braced with struts rising from the cradle and padded with plywood and plastic foam. The work on the cradle was scheduled to start Wednesday, August 14. Until then, Ryan Phillip, the archeological monitor of the William Self crew, would keep an eye on the boat. Setting up to Pull the Boat OutCasebolt and I arrived at the site on the morning of the 14th and spent several hours watching as the last of the water was pumped out from around the hull. A crew from JBL Construction handled the pumps and provided laborers for digging and carpentry work, while a two-man crew from Sheedy came to build the cradle. We spent two frustrating days trying to get the cradle in place. The basic idea was to lay the longitudinal 8x8 I-beams just outside the line of the hull and then dig narrow tunnels under the hull, using a water jet, to allow the 6x6 beams to be passed across on top of the 8x8s. Sheedy finally brought in the water jet, and McGuire of Lend Lease directed one of the big earth movers to dig down along the south side of the hull to provide a bed for the longitudinal 8x8. It was nerve-wracking to watch huge scoop buckets digging close to the fragile hull, but the skilled operators never touched the boat. By the next morning, we had the northern 8x8 in rough position, but still had to lower the forward end of it by a foot or so. Unfortunately, the forward end, to the east, came up against the steep bank of the excavation. The laborers spent the whole afternoon trying to dig out enough space to position the beam, only to have wet sand fill back in as fast as they could dig it out. We had a lot of trouble with the pump. Whenever it slowed or stopped, the water immediately began to rise. We were frequently wading through a foot or more of water, sinking deep into the slimy sand, with our boots trapped and threatening to be sucked off our feet. We positioned the first of the cross beams toward the stern of the lighter and clamped it into place. By the end of the day, we realized we couldn't get the north-side longitudinal girder properly placed without cutting further into the bank of the excavation. A batch of heavy I-beam piers was stored at the top of that bank, and McGuire decided that digging into the bank would be too dangerous until the beams could be moved. He stopped the job and told us we would have to wait until the middle of the following week to start again. A Second Try on the CradleOn August 21, we began again, and with help from Phillip, used the water jet to tunnel for the rest of the cross beams, then slid them through and welded them. We laid plywood strips covered with plastic foam over the beams and rigged up temporary supports for the ends of the boat. We returned the morning after to find that two of the planks in the bow transom had dropped off onto the sand. Somewhat discouraged, we rested the displaced planks inside the boat. Our temporary blocking had not been sufficient, allowing sand to wash back into the boat. Phillip and I spent much of the morning troweling sand out of the hull. Meanwhile, the JBL crew installed plywood and 2x4 side panels against the hull and built a better system of support for the overhanging transoms. The Lend Lease site bosses were running out of patience and told us to have the boat ready to move by 1 p.m. We all hustled, and by early afternoon were finally ready. The Lighter is LiftedIn front of a crowd of people from Tishman-Speyer, the William Self group, and SF Maritime NHP, we lifted the boat on its cradle without difficulty at about 2:30 p.m. and placed it on the upper level of the job site. The Sheedy crew added welded bracing before loading the boat onto a flatbed truck and transporting it to their yard for the night. Early the next day, it crossed the Bay Bridge and arrived at our San Leandro warehouse. In a sense, the tricky part had just begun. During the months since August 2013, the hull has been treated with a mixture of water and polyethylene glycol. The support structure was modified as needed to get access to all parts of the structure, and we have begun to plan how to most effectively support the boat for display purposes. With luck, the Charles Hare lighter will be ready for display sometime in 2015.

Photo courtesy © William Self Associates |

Last updated: February 23, 2025