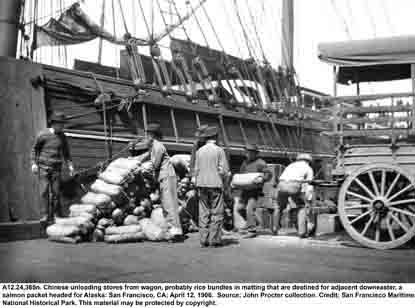

NPS Photo, A12.24365 We at San Francisco Maritime are particularly concerned with these cannery gangs because our ship Balclutha carried Asian workers north from San Francisco to Alaska each year between 1905 and 1930. As many as 100 men were housed in the forward end of the ’tweendeck, an area known as “Chinatown.” A portion of this area has been refurbished and is part of the “Cargo Is King” exhibit located in the ’tweendeck. By the time our ship entered the salmon canning business, the pattern of labor management was well established. Cannery gangs were recruited and managed by independent labor contractors, who were paid for the season on the basis of the number of cases packed. Almost from the beginning, these contractors were themselves Chinese. Chinese workers immediately proved themselves to be well suited to salmon cannery work. They brought physical deftness and discipline that was grudgingly admired, even given the anti-Asian tenor of the times. The development of the canning industry, beginning on the Columbia River, spreading to Puget Sound, and finally to Alaska, was based on the work of Chinese immigrant gangs. The labor contractor was seen as an essential bridge between the Chinese crews and the cannery managers. Most of the Chinese spoke little or no English, and worked under the supervision of a Chinese-speaking foreman. This system had obvious potential for abuse. The labor contractors were responsible for recruitment, provisioning, establishing working conditions, and setting pay scales for their gangs, all without oversight by the cannery owners. The system was open to kickbacks, favoritism, inadequate provisions and living conditions, and to the blacklisting of anyone who complained. Yet overall, the skill and reliability of the Chinese work force was recognized as being essential to the growing industry, and the wages were comparable to other opportunities open to the Chinese immigrants. Following the Exclusion Act of 1882, which outlawed new Chinese immigration, the older generation of skilled workers was very highly valued within the cannery workforce. After 1885, as the effects of the Exclusion Act began to be felt, the Japanese government opened immigration to its citizens, and a wave of Japanese workers arrived to partially fill the void in the cannery workforce. Working initially under the old Chinese contractors, the Japanese newcomers gradually found acceptance, and enterprising individuals rose to become foremen, and finally independent labor contractors. The Japanese never fully displaced the old Chinese hierarchy, but they came to form a significant percentage of the workforce. The last major wave of Asian immigrants to join the cannery gangs were the Filipinos, who arrived in significant numbers beginning in the early 1920s. Changes to the immigration laws in 1921 and 1924 barred most Japanese, but the Filipinos were American subjects, with free access to the nation’s labor market. By the later years of the 1920s, the Filipinos became an important element in the mix, particularly in the gangs sailing out of Seattle, which by that time rivaled San Francisco as a supply point for the Alaskan salmon industry. Again, some of these “Alaskeros” worked their way into the ranks of contractors, continuing the old patterns of labor management. The old system of contract labor began to come apart in the first half of the 1930s. The newly formed Alaska Cannery Workers Union at San Francisco was able to force the investigation and finally the criminal conviction of a notoriously corrupt contracting firm in 1934. A separate organizing effort at Seattle was spearheaded by Filipino workers, and the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union was established at about the same time. The assassination of two union officials in 1936 helped to galvanize support for the Seattle union, which finally included workers of all ethnic backgrounds. Union representation for the cannery workers was finally won in 1938, and the two separate unions ultimately united as the Alaska Cannery Workers Union. As we celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in May, we do well to recall the contributions of these generations of hard-working immigrants to the salmon packing industry. An excellent treatment of this story can be found in Organizing Asian American Labor: The Pacific Coast Canned-Salmon Industry, by Chris Friday, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1994. This book is available at the park library, 415-561-7030. By Stephen Canright, Park Curator, Maritime History |

Last updated: February 7, 2025