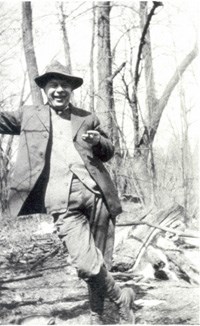

NPS image collection History of Indiana Dunes National ParkThe legislation that authorized Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 1966 resulted from a movement that began in 1899. Three key individuals helped make Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore a reality: Henry C. Cowles, a botanist from the University of Chicago; Paul H. Douglas, Senator for the State of Illinois; and Dorothy R. Buell, an Ogden Dunes resident and English teacher. Henry Cowles published an article entitled "Ecological Relations of the Vegetation on Sand Dunes of Lake Michigan," in the Botanical Gazette in 1899 that established Cowles as the "father of plant ecology" in North America and brought international attention to the intricate ecosystems existing on the dunes. But Cowles' article and the new international awareness were not enough to curtail the struggle between industry and preservation that governed the development of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. In 1916, the region was booming with industry in the form of steel mills and power plants. Hoosier Slide, for example, 200 feet in height, was the largest sand dune on Indiana's lakeshore. During the first twenty years of the battle to save the dunes, the Ball Brothers of Muncie, Indiana, manufacturers of glass fruit jars, and the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company of Kokomo carried Hoosier Slide away in railroad boxcars. It was this kind of activity by local industry that spurred Cowles, along with Thomas W. Allinson and Jens Jensen to form the Prairie Club of Chicago in 1908. The Prairie Club was the first group to propose that a portion of the Indiana Dunes be protected from commercial interests and maintained in its pristine condition for the enjoyment of the people. Out of the Prairie Club of Chicago came the precursor to the current park: The National Dunes Park Association (NDPA). The NDPA promoted the theme: "A National Park for the Middle West, and all the Middle West for a National Park."

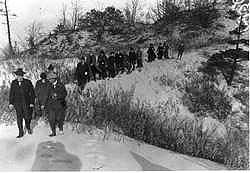

On October 30, 1916, only one month after the National Park Service itself was established (August 25, 1916), Stephen Mather, the Service's first Director, (shown at the far left in the adjacent photo leading a tour of park advocates in the dunes in 1916) held hearings in Chicago to gauge public sentiment on a "Sand Dunes National Park". Four hundred people attended and 42 people, including Henry Cowles, Jens Jensen, Lorado Taft and Harriet Monroe spoke in favor of the park proposal; there were no opponents. The battle for a national park was crippled, however, when the United States entered the First World War. National priorities changed and revenues were targeted for national defense, not the development of a national park. The popular slogan "Save the Dunes!" became "First Save the Country, Then Save the Dunes!" As the nation went from a world war into a depression, hopes to save the dunes began to fade.

NPS image collection In 1926, after a ten-year petition by the State of Indiana to preserve the dunes, the Indiana Dunes State Park opened to the public. The State Park was still relatively small in size and scope and the push for a national park continued. In 1949, Dorothy Buell became involved with the Indiana Dunes Preservation Council (IDPC). The efforts of Buell resulted in a Save the Dunes Council in 1952. However, the struggle did not end there. A union of politicians and businessmen desired to maximize economic development by obtaining federal funds to construct a "Port of Indiana." Hoosier politicians and businessmen were eager to exploit the economic prosperity promised by linking the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes via the St. Lawrence Seaway. In light of this, Save the Dunes Council President Dorothy Buell and council members like Charlotte Read and Sylvia Troy began a nationwide membership and fundraising drive to buy the land they desperately sought to preserve, known as the Central Dunes. Their first success was the purchase of 56 acres in Porter County, the Cowles Tamarack Bog.

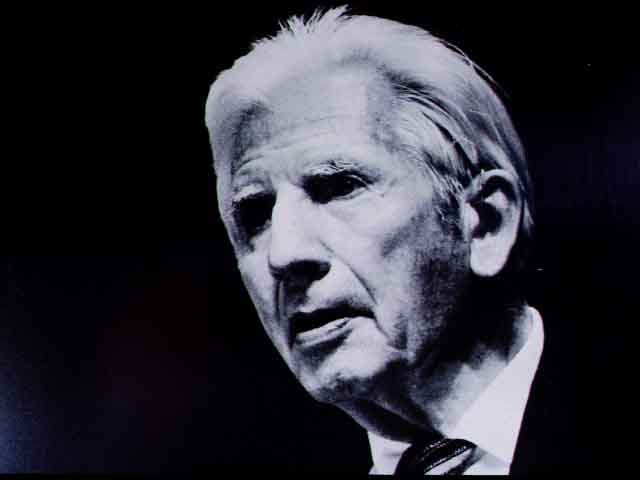

NPS image collection The Save the Dunes Council, sought political support to protect the dunes. In 1958, Dorothy Buell took advice to contact Senator Paul Douglas, who introduced his first bill to establish an Indiana Dunes unit within the National Park Service. This marked the beginning of one of the most prolonged legislative battles in U.S. history to protect a particular landscape. Dorothy Buell praised Douglas for his commitment, saying he had the “vision” and plunged into the fight. Thomas Dustin, director of the Indiana Izaak Walton League, offered a more measured view: “Until this time it had been an impossible campaign.” “But any expectation the council and its allies might have had of a quick victory now that Douglas was their champion soon died. While the park bills sat in committees, the industrial and political interests intent upon the development of the [Central Dunes] site exploited the customary advantage of private industry over conservationists in Congress—they simply proceeded to develop the land” (Sacred Sands). By 1962, most of the dune land had been sold off, and hope among conservationists began to wane. Although Save the Dunes continued to rally support, one undeniable fact hampered their efforts: industrial companies already owned nearly all the land. Despite the efforts of Senator Douglas and Save the Dunes, Bethlehem Steel remained unmoved. While the company had not yet secured the right to build, they had the authority to destroy. They contracted to haul away 2.5 million cubic yards of sand from the Central Dunes to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois—a bitter irony, as Northwestern students had long used the dunes for educational excursions. The news came as a great shock to Douglas and the rest of the Council. The next day Thomas Dustin called it “an infamous Pearl Harbor for conservationists everywhere.” Douglas and his allies insisted that Northwestern could not escape moral responsibility for the deed, but protests proved futile. Dorothy Buell remembered how in early winter 1962, as the bulldozers went to work, “Senator Douglas stood beside me, watching, with tears running down his cheeks” (Sacred Sands). In a final, desperate effort to save the Central Dunes, Senator Douglas introduced S. 650 at the start of the 1963 congressional session. “The bulldozers are poised, Mr. President, but the dunes still remain and can be rescued,” he declared. But it was no use. Within a year, the heart of the Central Dunes was gone. “The wildest and largest area of the Dunes outside the Indiana Dunes State Park, the center of maximum ecological diversity, the landscape of moving dunes where Cowles did his first research on plant succession—was no more” (Sacred Sands). A few years later, the battle over the lakefront culminated in what became known as the Kennedy Compromise, which established both a port and a park. While it was seen as a win for conservation, Senator Paul Douglas and Save the Dunes were deeply disappointed. They had faced a difficult choice: accept the compromise, which would create a federally protected lakeshore—albeit on land that felt was inferior to the dunes they had fought to preserve—or continue the battle indefinitely, risking the loss of everything. By the time the 89th Congress adjourned, the bill (Public Law 89-761) had passed on November 5, 1966 and the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore finally became a reality. While the 1966 authorizing legislation included only 8,330 acres of land and water, the Save the Dunes Council, National Park Service, and others continued to seek expansion of the boundaries of preservation. Four subsequent expansion bills for the park (1976, 1980, 1986, and 1992) have increased the size of the park to more than 15,000 acres. On February 15, 2019, Congress authorized the name change from Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore to Indiana Dunes National Park (Public Law No: 116-6; written into House Joint Resolution 31). Indiana Dunes became the 61st national park. |

Last updated: November 13, 2024