History of Paleontology in the National Park Service—Santucci, V. L. (page 4 of 9)

NPS image.

Introduction

Prior to the American Civil War (1861–1865), dreams of western expansion and the vast resources west of the Mississippi River motivated the people and leaders of the young nation. The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Louisiana Purchase, Mexican War and first migrations of pioneers across the western plains were collectively part of a "manifest destiny" shaping America during the 19th century. This was a formative period for the science of paleontology with early fossil discoveries capturing the attention of naturalists, geologists, political leaders and the public. Early fossil collections were routed to the handful of notable paleontologists and were directed to early museum and university collections for study and display.

Image courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art.

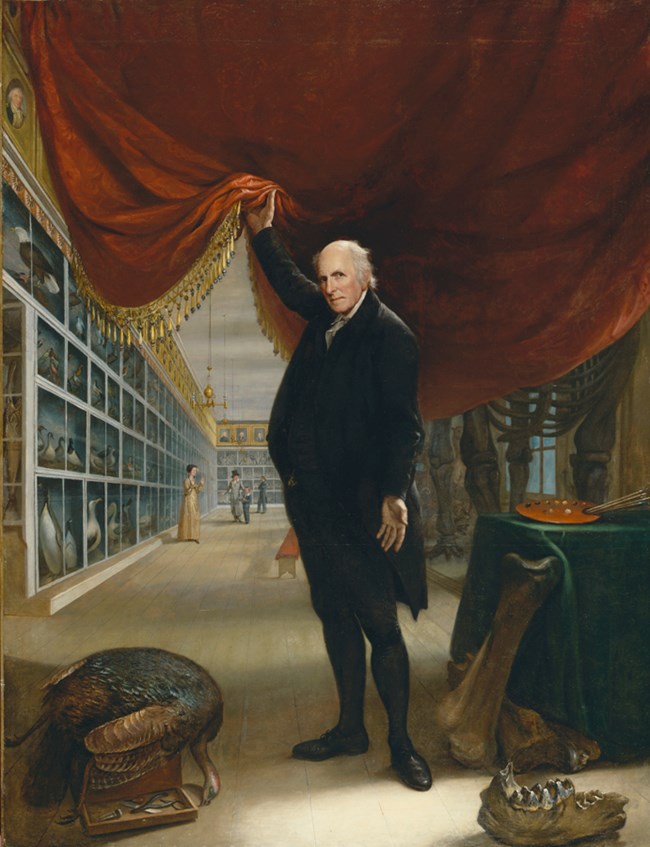

Establishment of Peale’s Museum in Philadelphia

The first recognized natural history museum in the United States was established by artist and naturalist Charles Willson Peale in Philadelphia. Originally known as the Philadelphia Museum, and later named Peale’s American Museum, the museum collection was located on the second floor of Independence Hall (known at the time as the Pennsylvania State House) between 1802 and 1827 (Schofield 1989). Peale’s museum exhibited his paintings of political and military leaders, as well as a large collection of natural history objects including fossils and a mastodon skeleton. This is an interesting footnote in the history of National Park Service paleontology, since Independence Hall is administered by the National Park Service as part of Independence National Historic Park.

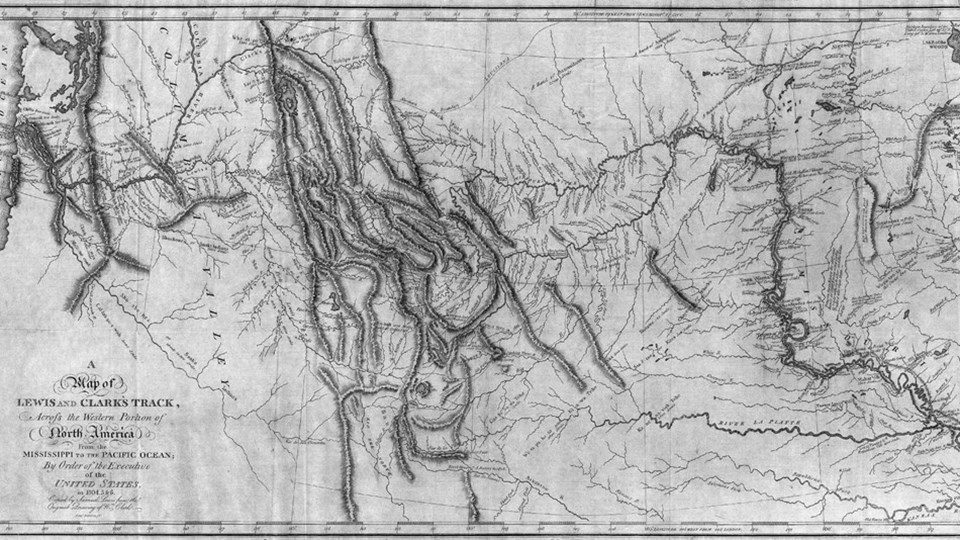

Lewis and Clark Expedition Discovers Fossils

President Thomas Jefferson may well have had the Peale mastodon in mind when he commissioned Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark to lead the first American expedition to explore the western territories. The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, was sanctioned shortly after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Among Jefferson’s instructions was a request to keep alert for mammoths, living or dead. The perilous journey began in May 1804 and lasted through September 1806. The expedition passed through a number of important fossil localities including Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, and the Falls of the Ohio fossil site, Indiana. Although no living mastodon was encountered, one important fossil specimen was collected from lands which would later be part of the National Park Service. This discovery was a fossilized jaw with teeth from a Cretaceous fish collected in August 1804 by a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The fossil fish was discovered near Soldier’s River in western Iowa (Harlan 1824), a tributary of the Missouri River and now a landmark along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

By the 1820s, the scientific understanding and acceptance of fossils had become more widespread and some of the first scientific descriptions of fossils from future National Park Service lands were emerging. The fossil fish jaw discovered in 1804 during the first months of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was described twenty years later and named Saurocephalus lanciformis in 1824 (Harlan 1824). Today this holotype fossil specimen is in the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. This is the only known surviving fossil collected by the Corps of Discovery and is also the oldest fossil that can be reliably attributed to an area administered by the National Park Service.

Early Fossil Discoveries at Vicksburg

French naturalist Charles A. Lesueur is credited for the first scientific documentation of fossils from Vicksburg National Military Park, Mississippi, in 1829, but his observations were not published until after his death (Dockery 1982; Kenworthy et al. 2007). British geologist Charles Lyell also collected fossil shells and corals from the Vicksburg Group from an area now within Vicksburg National Military Park on March 19, 1846 (Lyell 1849).

Mountain Man Jim Bridger’s Claims of “Peetrified Trees” in Yellowstone

It has been proposed that mountain man Jim Bridger’s report of the fossil forests of Yellowstone during the 1830s represents the first encounters of these resources by an American explorer. Bridger’s accounts of Yellowstone’s fossil forest were embellished by him and others as they were passed down over the years, but they provided an interesting example of the cultural history associated with these paleontological resources. According to one version of Bridger’s tale,

". . . peetrified birds a sittin’ on peetrified trees a singin’ peetrified songs in the peetrified air. The flowers and leaves and grass was peetrified, and they shone in a peculiar moonlight . . . that was peetrified too." (Chapman and Chapman 1935, p. 383)

These colorful legends captured the attention of other explorers who journeyed into Yellowstone later in the century.

Early Fossil Discoveries in the White River Badlands

One of the most important and interesting historical stories tied to National Park Service paleontology involves early collecting of fossils in the ‘mauvaises terres’ or ‘badlands’ of the Dakota Territory starting in the 1840s. The area is also referred to as the White River Badlands and has come to be known for the globally significant paleontological resources from the Eocene and Oligocene epochs of North America. The report and publication of fossil vertebrates from these prehistoric hunting grounds are linked to the birth of vertebrate paleontology as a science in North America. Some of the historically and scientifically important fossil localities in the White River Badlands are found today within Badlands National Park, South Dakota.

In 1843, a fossilized lower jaw with molars was collected in the badlands by a fur trader named Alexander Culbertson of the American Fur Company. This fossil specimen was transported back to St. Louis and into the hands of a physician named Dr. Hiram A. Prout. In 1846, Prout published a description and illustration of the jaw in the American Journal of Science, referring to the specimen as ‘Palaeotherium’ based on a European fossil mammal which appeared similar (Prout 1846). The publication of ‘Prout’s specimen’ captured the attention of the small community of paleontologists in the United States at that time, including Joseph Leidy (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia) and Spencer Baird (Dickinson College and Smithsonian Institution), prompting the first wave of a ‘fossil rush’ in the American west.

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

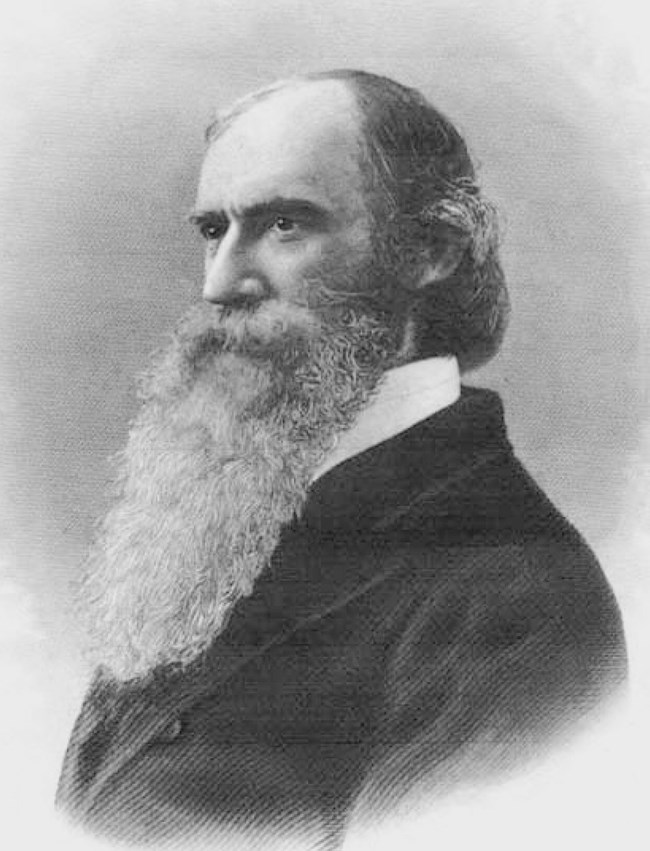

Additional fossils collected by Alexander Culbertson were studied and described by Dr. Joseph Leidy including the skull of the camel Poebrotherium (Leidy 1847). Leidy has been considered the ‘Father of Vertebrate Paleontology in North America’ and studied White River Badlands fossils early in his career. A series of geology and paleontology surveys ventured into the Dakota Badlands beginning with John Evans’s scientific expedition in 1849. Alexander Culbertson’s brother Thaddeus was hired by Spencer Baird to collect White River Badlands fossils for him while he was a professor at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania. With Baird’s move to the Smithsonian, the fossils were also forwarded to Washington, D.C. Field parties led by Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden and Fielding Bradford Meek during the 1850s resulted in additional collections of fossil vertebrates (O’Harra 1920; Benton et al. 2015).

Joseph Leidy described many of the new fossils coming out of the Dakota Territory, (O’Harra 1920; Benton et al. 2015). By 1854, Joseph Leidy had named 84 new species of fossil vertebrates from North America; all but seven were based on fossils collected in the White River Badlands (Leidy 1853, 1869; Benton et al. 2105).

Faculty and students from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City, South Dakota, have a long history of geology and paleontology field work in the White River Badlands dating back to 1899, and its Museum of Geology maintains one of the largest and most diverse collections of fossils from the Badlands acquired over more than a century of fieldwork. Similar fossils of mammals and turtles were observed by pioneers traveling the emigrant trail passing Scott’s Bluff (today within Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska) during the middle 1840s.

Reports of Fossils During Surveys in the Southwestern Territories

The first expeditions in the southwestern part of America began shortly after the end of the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848. The first plant fossil collected for scientific purposes in the Southwest was recovered from Canyon de Chelly by a military expedition led by Lieutenant J. H. Simpson on September 5, 1849 (Simpson 1852), likely within the modern boundaries of Canyon de Chelly National Monument. The expedition led by Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves is credited with the first documentation of the petrified wood from within a few miles of the ‘Arizona Petrified Forest’ on September 9, 1851. A federal government expedition led by Lieutenant Amiel W. Whipple named Lithodendron Creek in December 1853 (located today within Petrified Forest National Park) (Ash 1972).

Reports of Fossils from Alaska

One of the earliest historical accounts of fossil collecting in Alaska dates back to the 1850s, prior to the United States’ purchase of Alaska from Russia on March 30, 1867. Russian explorer and mining engineer Peter Doroschin made significant collections of fossils from a locality in south-central Alaska along the coast near Tuxedni Bay. This important locality was later named Fossil Point and today is within the boundaries of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Doroschin’s fossil collections were shipped to the Russian capital at St. Petersburg where they were ultimately studied, described and illustrated by Russian paleontologist Eduard von Eichwald (Eichwald 1871). The rich and well-preserved Middle Jurassic marine invertebrate fauna from Fossil Point, recognized during the mid-19th century when the area was part of Russian America, has continued to be the focus of scientific evaluation (Stanton and Martin 1905; Martin 1926; Imlay 1964; Detterman and Hartsock 1966; Blodgett and Santucci 2014; Blodgett et al. 2015).

Report of Fossils from the Western Territories

Benjamin Franklin Shumard, like Hiram Prout, was another prominent member of the St. Louis scientific circle. He is noted for his geological publications during the 1850s. Shumard worked in several areas now designated as national parks including: Santa Fe National Historic Trail, Guadalupe Mountains National Park, and Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Shumard was one of the organizers involved with the first government-sponsored geological surveys, at the state, territory, and federal levels. This group also included David Dale Owen, James Hall, Fielding Bradford Meek, and Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden, and were particularly active during the 1850s. These geologists documented the rocks and fossils of many midwestern and southwestern parks. In addition to Badlands National Park, Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Mississippi National River & Recreation Area, and Santa Fe National Historic Trail, they worked in the Missouri National Recreational River, Niobrara National Scenic River, and St. Croix National Scenic River during the pre-Civil War expeditions. Owen and Shumard died during the 1860s, but the others remained active into the 1870s.

Early Dinosaur Discovery at Springfield Armory

The first report of a dinosaur fossil associated with a National Park Service unit dates to the 1850s. In 1855, blasting for the Water Shops at Springfield Armory in Massachusetts (now Springfield Armory National Historic Site) uncovered the remains of a small Lower Jurassic dinosaur (Santucci 1998a). The remains were sent to Edward Hitchcock, the pioneering paleoichnologist and president of Amherst College, and were described by his son Edward Jr. as Megadactylus polyzelus in 1865 (Hitchcock 1865). Taxonomic revision of the specimen from Springfield Armory resulted in the assignment of the genus Anchisaurus (Tweet and Santucci 2011).

Reports of Fossils on the Southern Colorado River

During the 1857–1858 J. C. Ives expedition along the Colorado River, John Strong Newberry discovered the first fossils from the area which is now within Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Nevada. Newberry (1861) reported finding a single mammoth tooth at the base of a hill on the east side of the Colorado River (today the locality is along the Lake Mohave arm below Hoover Dam). The hill is now known as ‘Elephant Hill’ in reference to the mammoth tooth discovery. Newberry also reported reworked Paleozoic fossils in rocks observed along the Colorado River.

Union Soldiers Collect fossils During the Civil War

By 1861, the country was embroiled in a civil war and the focus of the people was redirected towards the national crisis and military conflict. There are a few interesting historical accounts of fossils during the American Civil War. Fort Washington Park is situated along the bank of the Potomac River south of Washington, D.C. The fort was one of the federal defenses of the capital city where Union soldiers were stationed during the war. One of the soldiers, named Valentine Sticher, wrote about life at the fort between April and July 1861, the first months of the war. There are two entries in Sticher’s diary which refer to fossil collecting at Fort Washington (Thompson 1910):

"June 10, 1861, Lieutenant Nagle, Wallace, and myself went up to ravine to look for petrified shells. . . . July 11, 1861, Cambell, Atkins, and Hartz started for Washington. Weather fine. Went up ravine again; found turtle heads (folk name for Cucullaea gigantae fossils). [H]ard work to dig them out. Dobson, Esterly, and Judge Foster came." (Thompson 1910, p. 105)

One final Civil War period historical note involving National Park Service fossils is linked to the western explorer and U.S. Geological Survey director, John Wesley Powell. During the siege at Vicksburg, Powell collected fossils from earthworks on the battlefield (now within Vicksburg National Military Park) in 1863 while serving for the Union Army (Moring 2002).

1865–1916

Early National Parks & Monuments

Related Links

-

Badlands National Park (BADL), South Dakota—[BADL geodiversity Atlas] [BADL Park Home] [BADL npshistory.com]

-

Canyon de Chelly National Monument (CACH), Arizona—[CACH Geodiversity Atlas] [CACH Park Home] [CACH npshistory.com]

-

Guadalupe Mountains National Park (GUMO), Texas—[GUMO Geodiversity Atlas] [GUMO Park Home] [GUMO npshistory.com]

-

Independence National Historical Park (INDE), Pennsylvania—[Geodiversity Atlas] [INDE Park Home] [INDE npshistory.com]

-

Lake Clark National Park and Preserve (LACL), Alaska—[LACL Geodiversity Atlas] [LACL Park Home] [LACL npshistory.com]

-

Lake Mead National Recreation Area (LAME), Arizona and Nevada—[LAME Geodiversity Atlas] [LAME Park Home] [LAME npshistory.com]

-

Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail (LECL), ID, IL, IA, KS, MO, MT, NE, ND, OR, SD, and WA—[Geodiversity Atlas] [LECL Park Home] [LECL npshistory.com]

-

Mississippi National River and Recreation Area (MISS), Minnesota—[MISS Geodiversity Atlas] [MISS Park Home] [MISS npshistory.com]

-

Missouri National Recreational River (MNRR), Nebraska and South Dakota—[MNRR Geodiversity Atlas] [MNRR Park Home] [MNRR npshistory.com]

-

Niobrara National Scenic River (NIOB), Nebraska—[NIOB Geodiversity Atlas] [NIOB Park Home] [NIOB npshistory.com]

-

Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO), Arizona—[PEFO Geodiversity Atlas] [PEFO Park Home] [PEFO npshistory.com]

-

Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway (SACR), Minnesota and Wisconsin—[SACR Geodiversity Atlas] [SACR Park Home] [SACR npshistory.com]

-

Santa Fe National Historic Trail (SAFE), CO, KS, MO, NM, and OK—[SAFE Geodiversity Atlas] [SAFE Park Home] [SAFE npshistory.com]

-

Springfield Armory National Historic Site (SPAR), Massachusetts—[SPAR Geodiversity Atlas] [SPAR Park Home] [SPAR npshistory.com]

-

Vicksburg National Military Park (VICK), Louisiana and Mississippi—[VICK Geodiversity Atlas] [VICK Park Home] [VICK npshistory.com]

-

Yellowstone National Park (YELL), ID, MT, and WY—[YELLL Geodiversity Atlas] [YELL Park Home] [YELL npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 27, 2023