History of Paleontology in the National Park Service—Santucci, V. L. (page 5 of 9)

NPS image.

Introduction

This period spans from the end of the American Civil War in 1865 through the creation in 1916 of the National Park Service as a bureau within the Department of the Interior. The period is marked by a renewed interest in westward expansion and exploration of new resources and opportunities. With increasing visitation and settlement in the west, the natural landscape was becoming more modified by development, exploitation of resources and conflict with Native Americans and earlier settlers. The voices of conservation and preservation of natural and cultural resources recognized the need to protect sensitive archeological sites and natural wilderness. The establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 gave birth to an idea that flourished during the beginning of the 20th century with the passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906 and the creation of the National Park Service in 1916.

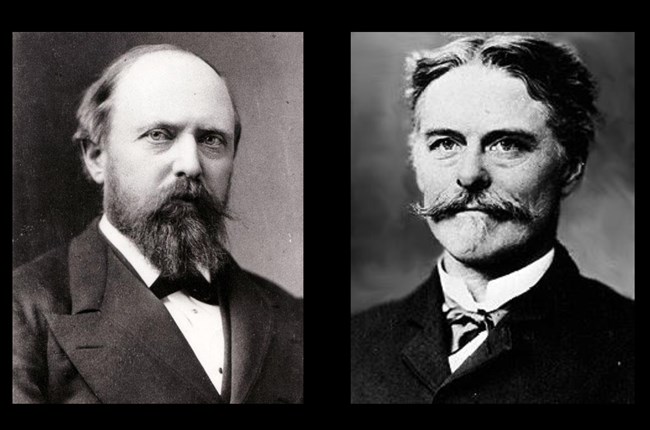

This post-Civil War period is a colorful time for American paleontology with some academic rivalries and competition pertaining to the new fossil discoveries from the western territories. The famous ‘Bone Wars’ waged between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh have become legendary tales based upon the bitter scientific feud. Other individuals worked more independently in more remote locations of the western frontier to uncover the fossilized remains of ancient organisms previously unknown. Thomas Condon is one of the pioneer paleontologists who searched for fossils in the John Day Basin (later established as John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon) beginning in the 1860s.

The history of paleontology associated with the National Park Service during this period often includes stories which predate the concept of the Service and the establishment of specific areas as national parks. However, it is important to remember that on some occasions scientifically significant fossil localities in the American West are part of areas later designated as national parks or monuments. Once a fossil locality is transferred and incorporated into lands administered by the National Park Service, the management, protection and stewardship of the paleontological resources becomes its responsibility.

The Great Surveys of the Western Territories Yield Fossils and Inspire ‘America’s Best Idea’

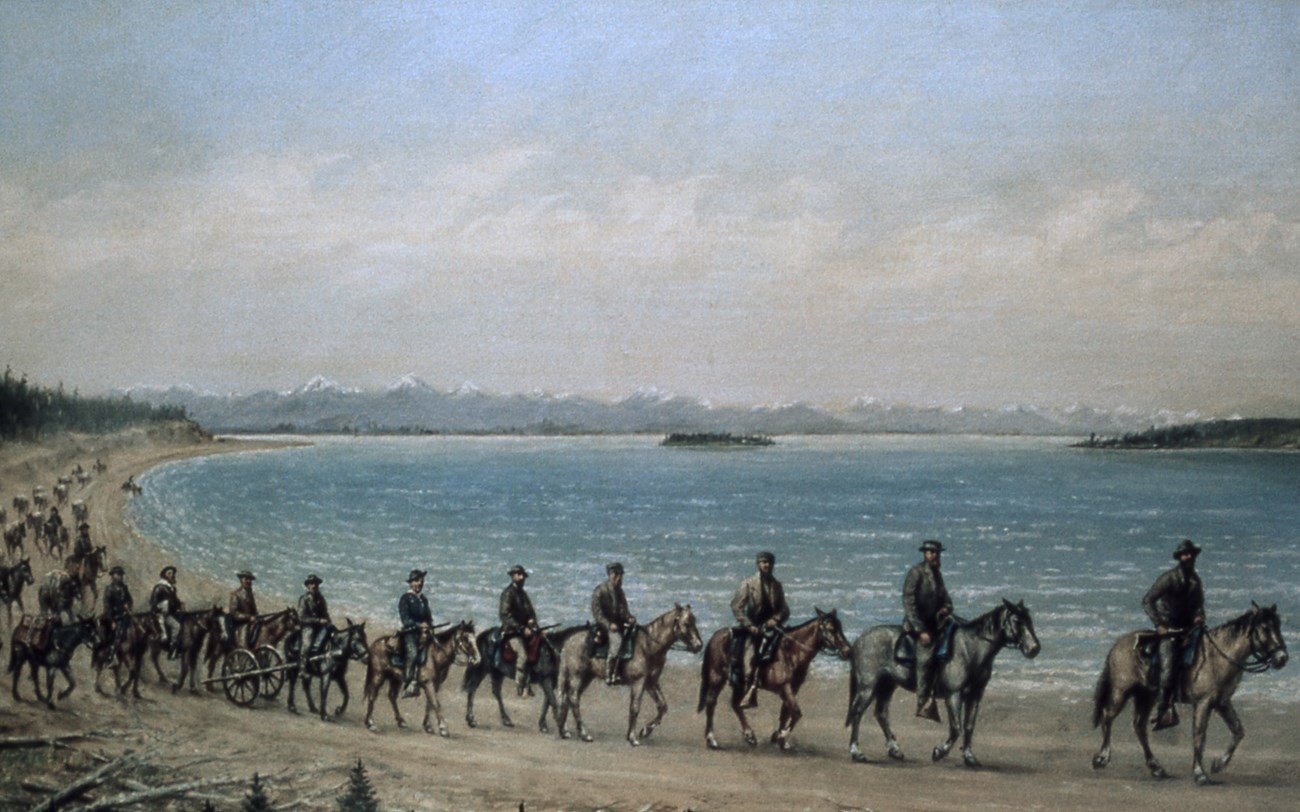

After the American Civil War, there was a renewed focus by the United States government directed towards the resources of the western territories. Congress supported the funding of a series of scientific surveys to map and document the west between 1867 and 1879. The four ‘Great Surveys’ of the American West were primarily focused on the territories west of the 100th meridian and were led by Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden, Clarence King, Major John Wesley Powell, and Lt. George Wheeler (Bartlett 1980).

The U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories was led by geologist and surgeon Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden between 1867 and 1878. The ‘Hayden Survey’ was a scientific expedition which explored northwestern Wyoming including the Yellowstone region and the headwaters of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. Hayden recruited artist Thomas Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson to accompany the survey team into Yellowstone and visually document the resources and landscapes. These images and illustrations complemented the scientific reports and descriptions of the flora, fauna and geology of Yellowstone. In December 1871, bills were introduced in the U.S. Congress to preserve Yellowstone as a national park. On 1 March 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act (17 Stat. 32) creating the world’s first national park and what is considered by some ‘America’s Best Idea’.

The first fossil collections from the area now within Yellowstone National Park, in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, are attributed to the Hayden Survey of 1871. The fossil leaves obtained during the expedition were studied and described by paleobotanist Leo Lesquereux (Lesquereux 1872). William Henry Holmes accompanied the Hayden Survey and was the first to report the occurrence of petrified wood near Junction Butte and in the cliffs of the Lamar River Valley, the first to interpret the existence of successively buried fossils forests in Yellowstone, and the first to report invertebrate fossils from Yellowstone (Holmes 1878, 1879). In 1878 Holmes accompanied cartographer Henry Gannett to the summit of the peak now named Mount Holmes, where they found marine fossils, including trilobites, on a ridge just below the summit that was later named Trilobite Point (Santucci 1998b).

The U.S. Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel was led by civilian scientist Clarence King between 1867 and 1878. This survey was sponsored by the U.S. Army and focused on producing maps and scientific reports on the resources along the 40th parallel from northeastern California, through Nevada, and into the eastern Wyoming Territory. King also evaluated mineral resource potential during mapping and evaluation of resources.

The U.S. Geographical Survey West of the 100th Meridian was led by First Lieutenant George Montague Wheeler between 1869 and 1879. The ‘Wheeler Survey’ was administered under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In 1869, Wheeler’s expedition visited the area now within Great Basin National Park, Nevada, and in 1871 visited areas now part of Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, and Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Arizona and Nevada, but only small collections of fossils were made.

The U.S. Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region was led by Major John Wesley Powell between 1869 and 1879. During the Civil War, Powell was involved at the siege at Vicksburg and documented fossils from some exposed strata in the fortifications trenches. Powell would become the second Director of the U.S. Geological Survey and served between 1881 and 1894.

The ‘Powell Survey’ was a legendary adventure down the Green and Colorado rivers and through the Grand Canyon. In 1870 Powell obtained funding from Congress to support his river trip which started in Green River, Wyoming Territory. Powell is credited with the collection of a fossil coral specimen near Echo Park and Split Mountain Canyon, an area which is now within Dinosaur National Monument. The specimen represents the holotype specimen for the fossil coral Amplexus zaphrentiformis (White 1876), and it was discovered nearly half a century before the first dinosaurs were reported from the area now within Dinosaur National Monument.

Excavation of Ice Age Fossils from Port Kennedy Bone Cave

Port Kennedy Bone Cave is an important Pleistocene fossil locality which was uncovered and excavated in 1870 and again in 1896. The ‘cave’, likely representing a sinkhole that many animals fell into, is located within what is now Valley Forge National Historical Park, Pennsylvania. More than 1,200 fossil specimens were collected during the quarrying of Port Kennedy Bone Cave and they are curated into the collections at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and the American Museum of Natural History in New York (Daeschler et al. 1993). The fossils were originally studied and described by paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope (Cope 1871, 1899; Mercer 1899). Cope named 39 species of Pleistocene vertebrates collected from Port Kennedy Bone Cave, including several well-known taxa such as Smilodon gracilis (saber tooth cat) and several species of Megalonyx (ground sloth).

Early Fossil Discoveries from the Florissant Fossil Beds

The diverse and exceptionally well-preserved plant and insect fossils of Florissant (the area later designated as Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument) in Colorado came to light during the early scientific surveys of the American West. In 1873, Arthur C. Peale, the geologist for the Hayden Survey, wrote:

When the mountains are overthrown and the seas uplifted, the universe at Florissant flings itself against a gnat and preserves it. (Peale 1873).

The early collections of fossils from Florissant for Princeton University in 1877 and the government surveys resulted in many scientific publications describing the fossil plants (Lesquereux 1878, 1883), fossil insects (Scudder 1890, 1900), and fossil vertebrates (Cope 1875). Between 1906 and 1908, Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell made fossil collections that resulted in nearly 130 publications on the paleontology of the Florissant Fossil Beds (Cockerell 1908a, 1908b).

Mammoth Remains Discovered on the Channel Islands

The scientific discovery of mammoth fossils on the Channel Islands is obscured by history. It is known that a mammoth tooth and tusk were located by a man named W. G. Blunt on Santa Rosa Island during surveying work, and that he collected the tooth and gave it to the California Academy of Sciences, from which it appears to have been lost (probably during the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and following fire). There is a note in the Proceedings of the Academy from April 1873 that refers to his donation, with the name of the island accidentally given as “Santa Barbara Island” (California Academy of Sciences 1873). A slightly longer discussion appears in the September 1873 proceedings (Stearns 1873). Recent authors have usually attributed the find to the mid-1850s, but this appears to be based on equating W. G. Blunt with George William Blunt. However, W. G. Blunt assisted other investigators on the islands in 1890, while George William Blunt died in 1878. W. G. Blunt himself told another researcher that he found the tooth in 1871 (Voy unpublished ms. 1890–1893). It is from the 1890 investigations that we get the first clear indication that the Channel Islands were populated by a species of pygmy mammoth, reduced in size by their environment.

Fossils Discovered in the Big Bend Area

The Trans-Pecos area of Texas, which would later become part of Big Bend National Park, has a long and rich history of paleontological exploration, collecting, and research. Reports of fossils from the area date back to the late 1880s with collections of fossil invertebrates and invertebrates made by the ‘Dumble Survey’ of 1888 (Dumble 1895). Geologist John Udden mapped, studied, and described the Cretaceous strata of the Big Bend region in 1907 (Udden 1907). Udden reported the occurrence of petrified logs and the remains of what he referred to as ‘saurian bones’ from the Rattlesnake Beds.

Investigation of the Bone Bed at Agate Ranch

A rich paleontological history is associated with the Agate Springs Ranch, which would later be preserved as Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska. The ranch has sometimes been referred to as the ‘Great Bone Bed at Agate’ where the fossils were discovered in the 1880s by James H. Cook and his wife Kate (Cockrell 1986). The locality was visited by some of the most notable paleontologists during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and helped define the understanding of Miocene fossil vertebrates in North America. James Cook invited many paleontologists to the ranch to dig and study the fossils, including Othniel Charles Marsh (Yale University) and Edward Drinker Cope (from Philadelphia) (Vetter 2008).

James and Kate's first son, Harold James Cook, was born in 1887 and exhibited great interest in fossils from an early age. In 1892 Harold assisted paleontologist Erwin Barbour (University of Nebraska) excavate a large fossil burrow referred to as Daemonelix, now known to have been produced by ancient rodents.

Photograph by James St. John - Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37027739. With permission from the Archives and Special Collections of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Between 1904 and 1925, the fossil hills and quarries of Agate Ranch were visited by field crews from the American Museum of Natural History, Amherst College, Carnegie Museum, University of Nebraska and Yale University (Peterson 1906; Loomis 1910; Matthew 1923). Fossil excavations yielded thousands of mostly mammal bones. Eventually, the increasing number of paleontologists working at the ranch led to some rivalry between the institutions. Harold enjoyed working with everyone and in 1905 began to work closely with Olaf Peterson from the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. Harold also continued to work with Erwin Barbour from the University of Nebraska and was accepted as a student in their Geology Department in 1908 (Cockrell 1986).

In 1909, Harold was visited by paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn from the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Osborn offered the young Cook a research assistant position at Columbia University to study under Osborn, as well as vertebrate paleontologists William King Gregory and William Diller Matthew. In addition, Cook also met and corresponded with other distinguished paleontologists including Walter Granger, Frederic Brewster Loomis, Richard Swann Lull and William John Sinclair. The National Park Service maintains an extensive collection of archives associated with the Cook family including correspondence between the family and many of the paleontologists who visited and worked at Agate Springs Ranch.

Congress Authorizes the Antiquities Act

On June 8, 1906, the Antiquities Act (Public Law 59–209) was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt. The law was enacted in response to the widespread looting and vandalism of archeological sites in the American Southwest. One of the provisions of the Antiquities Act provided the president of the United States with the authority to proclaim national monuments (Santucci 2006). This authority to create national monuments does not require support from Congress and has been used over 100 times including when Waco Mammoth National Monument was proclaimed in 2015.

Saving the Petrified Forest of Arizona

NPS photo.

Several attempts to protect the Arizona petrified forest were undertaken by Congress during the 1890s. In 1900, Smithsonian paleobotanist Lester F. Ward published a ‘Report on the Petrified Forests of Arizona’ and recommended that the area needed to be protected (Ward 1900). During 1904 and 1905 conservationist John Muir traveled into the Arizona Territory with his daughter and ventured into the ‘Petrified Forest’ near the town of Adamana. Muir was both inspired by the fossil locality known as ‘Chalcedony Forest’ and unsettled by the wagon loads of petrified wood being hauled out. It is believed that John Muir communicated his observations and concerns about the petrified forest to his friend President Theodore Roosevelt (Lubick 1996).

On December 8, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt established Petrified Forest National Monument (Proclamation 697), one of the first monuments established using the Antiquities Act (Santucci 2006). The proclamation stated:

. . . the mineralized remains of Mesozoic forests, commonly known as the “Petrified Forest,” in the Territory of Arizona . . . are of the greatest scientific interest and value and it appears that the public good would be promoted by reserving these deposits of fossilized wood as a national monument with as much land as may be necessary for the proper protection thereof . . . (Theodore Roosevelt, Presidential Proclamation 697).

Paleontologist Charles Walcott Studies Fossils from Several National Parks

One of the most famous American paleontologists is Charles Doolittle Walcott. Walcott joined the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in 1879 and in 1894 became its third Director, a position he held until 1907. In 1907 Walcott became the fourth Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and served in that position until 1927. During his career, Charles Walcott either conducted fieldwork in, or studied fossils which were collected from areas that would become national parks, including Death Valley National Park, Glacier National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Teton National Park, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Ozark National Scenic Riverways, Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway, and Yellowstone National Park (Walcott 1883, 1890, 1899, 1901, 1902, 1906, 1914a, 1914b). Walcott was a strong advocate and supporter of the National Park Service during the early years of the new bureau, and in 1917 was an invited speaker at the Fourth National Park Conference (Walcott 1917).

World Renowned Dinosaur Discoveries and the Establishment of Dinosaur National Monument

NPS photo.

During 1908 the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, applied for and was granted an Antiquities Act Permit from the Secretary of the Interior to prospect and collect fossils from federal lands in Uintah County, Utah. This was the first such permit issued for fossils under the authority of the Antiquities Act, two years after the passage of the legislation by Congress. After the permit was issued in 1908, Carnegie Museum director William Holland discovered the femur of a sauropod dinosaur from the Morrison Formation near Jensen, Utah. The following year, Holland sent paleontologist Earl Douglass to continue paleontological field work in the dinosaur producing beds of northeastern Utah (Holland 1915a, 1915b, 1924; McIntosh 1977; Chure and McIntosh 1990). Excavations at the Dinosaur Quarry, sometimes referred to as the ‘Douglass Quarry’, continued until 1922, resulting in the collection of one of the most important assemblages of dinosaur skeletons in the history of paleontology.

On October 4, 1915, Dinosaur National Monument was established by President Woodrow Wilson as the second fossil park (the first was Petrified Forest National Monument) proclaimed by the Antiquities Act. According to the proclamation the monument was established to preserve:

. . . an extraordinary deposit of Dinosaurian and other gigantic reptilian remains of the Jurassic period, which are of great scientific interest and value, and it appears that the public interest would be promoted by reserving these deposits as a National Monument, together with as much land as may be needed for the protection thereof. (Woodrow Wilson, Presidential Proclamation 1313).

Discovery and Excavation of the Cumberland Bone Cave

During 1912, an important fossiliferous cave deposit was discovered during construction of the Western Maryland Railway. Excavation of a cut in a ridge near Cumberland, Maryland, exposed fossil bones which were brought to the attention of local naturalist Raymond Armbruster. Paleontologist James Gidley at the Smithsonian Institution was notified and visited this fossil locality, given the name Cumberland Bone Cave. Gidley supervised excavation of Cumberland Bone Cave between 1912 and 1916. Forty-one genera of mammals were originally identified from within the cave deposits, many representing extinct Pleistocene fauna including saber-tooth cat and cave bear specimens (Gidley 1913; Gidley and Gazin 1938). Today the area which was part of the Cumberland Bone Cave is along the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail near Cumberland, Maryland.

1916–1966

First 50 Years of the NPS

Related Links

-

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (AGFO), Nebraska—[AGFO Geodiversity Atlas] [AGFO Park Home] [AGFO npshistory.com]

-

Big Bend National Park (BIBE), Texas—[BIBE Geodiversity Atlas] [BIBE Park Home] [BIBE npshistory.com]

-

Death Valley National Park (DEVA), California and Nevada—[DEVA Geodiversity Atlas] [DEVA Park Home] [DEVA npshistory.com]

-

Channel Islands National Park (CHIS), California—[CHIS Geodiversity Atlas] [CHIS Park Home] [CHIS npshistory.com]

-

Dinosaur National Monument (DINO), Colorado and Utah—[DINO Geodiversity Atlas] [DINO Park Home] [DINO npshistory.com]

-

Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument (FLFO), Colorado—[FLFO Geodiversity Atlas] [FLFO Park Home] [FLFO npshistory.com]

-

Glacier National Park (GLAC), Montana—[GLAC Geodiversity Atlas] [GLAC Park Home] [GLAC npshistory.com]

-

Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), Arizona—[GRCA Geodiversity Atlas] [GRCA Park Home] [GRCA npshistory.com]

-

Grand Teton National Park (GRTE), Wyoming—[GRTE Geodiversity Atlas] [GRTE Park Home] [GRTE npshistory.com]

-

Great Basin National Park (GRBA), Nevada—[GRBA Geodiversity Atlas] [GRBA Park Home] [GRBA npshistory.com]

-

Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSM), North Carolina and Tennessee—[GRSM Geodiversity Atlas] [GRSM Park Home] [GRSM npshistory.com]

-

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (JODA), Oregon—[JODA Geodiversity Atlas] [JODA Park Home] [JODA npshistory.com]

-

Lake Mead National Recreation Area (LAKE), Arizona and Nevada—[LAKE Geodiversity Atlas] [LAKE Park Home] [LAKE npshistory.com]

-

Ozark National Scenic Riverways (OZAR), Missouri—[OZAR Geodiversity Atlas] [OZAR Park Home] [OZAR npshistory.com]

-

Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO), Arizona—[PEFO Geodiversity Atlas] [PEFO Park Home] [PEFO npshistory.com]

-

Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail (POHE), DC, MD, PA, and VA—[POHE Geodiversity Atlas] [POHE Park Home] [POHE npshistory.com]

-

Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway (SACR), Minnesota and Wisconsin—[SACR Geodiversity Atlas] [SACR Park Home] [SACR npshistory.com]

-

Yellowstone National Park (YELL), ID, MT, and WY—[YELL Geodiversity Atlas] [YELL Park Home] [YELL npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 27, 2023