History of Paleontology in the National Park Service—Santucci, V. L. (page 7 of 9)

Mural by Julius Csotonyi and Alexandra Lefort.

Introduction

This period is punctuated by the establishment of several National Park Service areas recognized in part for their significant paleontological resources. Perhaps this trend in the conservation of paleontological resources is a reflection of evolving societal values or human dimensions pertaining to fossils during this period (Santucci et al. 2016). This period includes a program called Mission 66, in which the National Park Service undertook a ten-year effort to dramatically expand visitor services by 1966, in time for the 50th anniversary of the agency. There were National Park Service paleontology-focused exhibits which were developed as part of Mission 66. During the second half of the twentieth century, an escalating commercial market for fossils sparked a corresponding public and political debate involving our paleontological heritage in the United States.

This period also marks the creation of the first service-wide National Park Service paleontologist position, the development of National Park Service policies pertaining to paleontology.

Establishment of Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument

On August 20, 1969, Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado, was established as a unit of the National Park Service. According to the authorizing legislation the monument was established:

in order to preserve and interpret for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations the excellently preserved insect and leaf fossils and related geologic sites and objects at the Florissant lakebeds . . . (Public Law 91-60).

The monument preserves abundant and diverse paleontological resources from the Eocene Florissant Formation. Fossil remains include incredibly well-preserved leaves, fruits, insects, fishes, birds, and small mammals that originally came to scientific attention in the early 1870s. Additionally, Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument contains impressive standing stumps of petrified redwood trees. Leopold and Meyer (2012) present a detailed historical account of the preservation movement which advanced to protect the Florissant Fossil Beds and creation of the national monument. Also see Early fossil discoveries from the Florissant Fossil Beds (1865–1916).

New Paleontological Discoveries at Big Bend National Park

Big Bend National Park was a ‘hot spot’ for paleontological field work and discoveries during the 1970s. Judith A. Schiebout uncovered Paleocene mammals during her dissertation field work that spanned the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary in Big Bend National Park (Schiebout 1973). In 1971, the remains of the largest known flying animal, a pterosaur named Quetzalcoatlus northropi, were uncovered by Doug Lawson (Lawson 1972, 1975). Lawson is also credited with describing ceratopsian and tyrannosaurid fossils from the park, and documenting a variety of paleobotanical specimens from Big Bend National Park (Lawson 1972, 1976). During the late 1970s, James and Margaret Stevens and Tom Lehman began their paleontological work in Big Bend National Park which spanned four decades and included many important fossil discoveries (Stevens 1977; Lehman 1985). Also see Fossils Discovered in the Big Bend Area (1865–1916) and Establishment of Big Bend National Park and Early Fossil Discoveries (1916–1966).

Establishment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park

On September30, 1972, Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas, was established as a unit of the National Park Service. According to the authorizing legislation:

In order to preserve in public ownership an area in the State of Texas possessing outstanding geological values together with scenic and other natural values of great significance. (Public Law 89-667, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 283-283e).

Although fossils are not specifically mentioned, they are certainly part of the park’s “outstanding geological values”. The Permian Reef Complex preserved within and around Guadalupe Mountains National Park represents one of the largest fossil reefs and the most complete Permian marine sequences in the world (Newell et al. 1953). The diverse marine fauna associated with the ancient reef ecosystem includes algae, fusulinids, sponges, corals, bryozoans, brachiopods, trilobites, ostracods, gastropods, cephalopods, scaphopods, pelecypods, crinoids, echinoids, conodonts and a few rare fish. A network of more than two dozen caves at Guadalupe Mountains National Park preserves Pleistocene and Holocene vertebrate fossils (Santucci et al. 2001).

Establishment of Fossil Butte National Monument

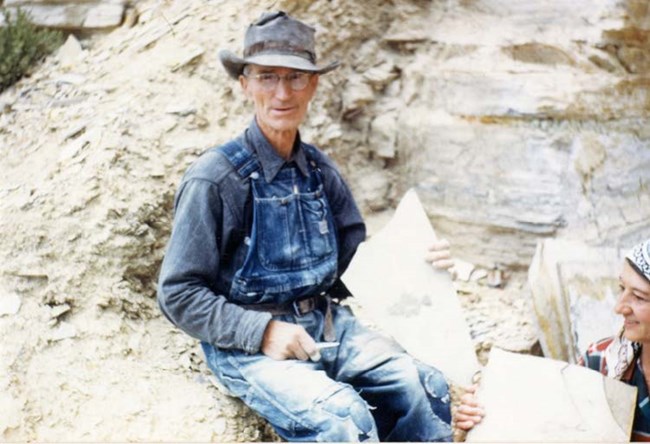

Photo by Walter Youngquist – FOBU 13666.

On October 23, 1972, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming, was established as a unit of the National Park Service. According to the authorizing legislation the monument was established:

. . . in order to preserve for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations outstanding paleontological sites and related geological phenomena, and to provide for the display and interpretation of scientific specimens, the Fossil Butte National Monument. (Public Law 92-537).

Fossil Butte National Monument contains lacustrine deposits from Eocene Fossil Lake, one of three ancient lakes representing the extremely fossiliferous Green River Formation. The extraordinary preservation of the fossils, including Eocene vertebrates, invertebrates, plants and trace fossils, at the locality is recognized as a Lagerstätten. The wonderful fossil preservation of the Green River Formation fossils has resulted in intensive commercial collecting of fossils on private and State of Wyoming lands in Fossil Basin for more than a century (Grande 1980).

Establishment of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

On October 8, 1975, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon, was established as a unit of the National Park Service. This monument encompasses three parcels of land in the John Day Basin preserving rich fossil assemblages from the Eocene into the Miocene, showing changing organisms over tens of millions of years. This area has been recognized for its significant fossils since the second half of the 19th century.

Redesignation of Badlands National Monument to National Park

On November 10, 1978, Badlands National Monument was redesignated as a national park (Public Law 95-625, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 441 - 441o). This redesignation included the expansion of the park boundary to include the area referred to as the ‘South Unit’ which incorporates lands on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. According to the Badlands National Park General Management Plan for the South Unit (2012), the purpose of the park is to:

. . . preserve, interpret, and provide scientific research of the paleontological and geological resources of the White River Badlands . . . .

The history related to the expansion of lands to be incorporated into Badlands National Park is complex and extends back to World War II. In 1942, the United States acquired most of the area now encompassed within the South Unit of the park to be used as a U.S. Air Force gunnery range. The lands were acquired through condemnation, and Native American families who lived on the condemned lands were displaced.

Federal legislation signed in August 1968 (Public Law 90-468), and a Memorandum of Agreement between the Oglala Sioux and the National Park Service in 1976, paved the way for the redesignation of Badlands National Park of 1978 to include the addition of the South Unit on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Also see Early fossil discoveries in the White River Badlands (1800–1865) and Establishment of Badlands National Monument (1916–1966).

Enactment of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act

The Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (Public Law 96–95, as amended, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 470aa et seq.) is the primary legal authority pertaining to the management of archeological resources on federal and Indian lands in the United States. Although the focus of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act applies to archeological resources, there is a provision which specifically addresses the occurrence of paleontological resources within an archeological context (Kenworthy and Santucci 2006).

Establishment of Bering Land Bridge and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Monuments Recognizing Fossils

Bering Land Bridge National Monument and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Monument were established as units of the National Park Service in Alaska on December 1, 1978. President Jimmy Carter proclaimed these monuments under the authority of the Antiquities Act (1906) and specifically referenced the paleontological resources of each monument. The Bering Land Bridge National Monument proclamation states:

paleontological sites providing abundant evidence of the migration of plants and animals onto the continent in the ages before the human migrations. The arctic conditions here are favorable to the preservation of this paleontological record from minute pollen grains and insects to the large mammals such as the mammoth. (Jimmy Carter, Proclamation 4614).

The Yukon-Charley Rivers National Monument proclamation references:

outstanding paleontological resources and ecologically diverse natural resources, offering many opportunities for scientific and historic study and research. [The proclamation further states] Geological and paleontological features within the area are exceptional, including a nearly unbroken visible series of rock strata representing a range in geologic time from pre-Cambrian to Recent. The oldest exposures contain fossils estimated to be 700 million years old, including the earliest forms of animal life. A large array of Ice Age fossils occurs in the area. (Jimmy Carter, Proclamation 4626).

Enactment of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act and Recognition of Scientific Significance of Alaska Parks

On December 2, 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter, and it re-designated both Bering Land Bridge National Monument and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Monument as national preserves and again reaffirmed the:

protection of the geological, archeological, paleontological, biological and other phenomena (Public Law 96-487, codified at 16 U.S.C. §§ 3101 et seq.).

ANILCA led to the large expansion of National Park Service lands in Alaska which preserve diverse and scientifically important paleontological resources.

Fossil Theft Investigation at Badlands National Park

During the summer of 1985, a law enforcement investigation at Badlands National Park, South Dakota, uncovered evidence involving long-term and systematic illegal collecting of fossils from within the park. This investigation yielded information indicating that some of the unauthorized fossil collecting in the park was potentially tied to commercial fossil dealers. Nearly a decade after the fossil theft investigation was initiated at Badlands National Park in 1985, the first felony conviction for fossil theft in U.S. history was issued to a commercial fossil business in 1995 for the theft of fossil fish from Badlands National Park (Fiffer 2000).

First National Park Service Fossil Resource Conference Hosted at Dinosaur National Monument

In 1986, the first National Park Service Fossil Resources Conference was hosted at Dinosaur National Monument. The conference was hosted by Dan Chure, paleontologist at Dinosaur National Monument, and Ted Fremd, paleontologist at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, in order to promote communication and collaboration between staff involved with the management, protection, interpretation, curation and research of National Park Service fossils. Chure and Fremd raised issues which contributed to development of service-wide policy and guidelines (NPS-77) pertaining to National Park Service fossils and led to the transfer of National Park Service paleontology from under the administration of the Cultural Resources Program to the Natural Resources Program. The birth of the fossil resource conference idea at Dinosaur National Monument in 1986 led to nine more similar conferences which expanded to involve other federal, state and local land managing agencies.

Establishment of Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

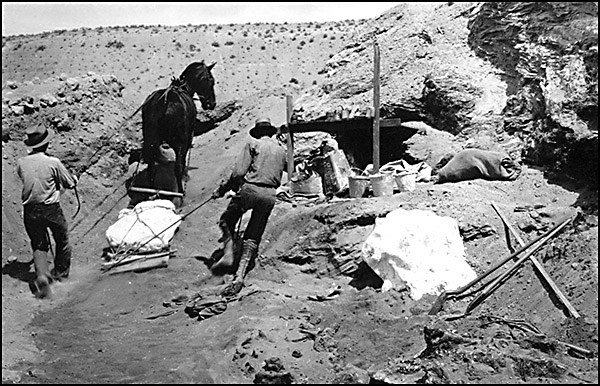

Smithsonian photograph.

On November 18, 1988, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho, was established as a unit of the National Park Service. According to the authorizing legislation the monument was established:

In order to preserve for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations the outstanding paleontological sites known as the Hagerman Valley fossil sites, to provide a center for continuing paleontological research, and to provide for display and interpretation of the scientific specimens uncovered at such sites, there is hereby established the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument. (Public Law 100-696).

Section 306 of the law states:

In order to provide for continuing paleontological research, the Secretary shall incorporate in the general management plan provisions for the orderly and regulated use of and research in the monument by qualified scientists, scientific groups, and students under the jurisdiction of such qualified individuals or groups. (Public Law 100-696).

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument preserves one of the world’s richest fossil deposits from the late Pliocene epoch. Among the scientifically significant fossils from the monument is the largest concentration of ‘Hagerman Horse’ fossils in North America.

First Assessment of National Park Service Paleontological Resource Crimes

In 1988 the Servicewide Natural Resources Assessment and Action Program recognized that the loss of paleontological resources through illegal collecting was a major resource issue facing the National Park System. A Paleontological Resources Protection Questionnaire was distributed to National Park Service areas in Spring 1992. This survey was primarily designed to gather data regarding the extent and magnitude of illegal fossil collection in the parks. The initial survey identified 721 incidents of paleontological resource crimes in the National Park Service, resulting in 412 citations and six arrests. Based on the results of the initial survey, a series of recommendations were implemented to enhance the protection of non-renewable paleontological resources in the National Park Service. One of the recommendations called for the need to develop and present paleontological resource protection training to National Park Service staff and law enforcement rangers. Between 1993 and 1999 more than 200 National Park Service rangers participated in paleontological resource protection training.

In 1999, the National Park Service Ranger Activities Division and the Geologic Resources Division distributed a Geological, Paleontological & Cave Resources Protection Survey to the parks. This survey was expanded from the 1992 survey to include incidents related to the theft or vandalism of any geologic resources, including fossils and cave resources, in the parks. The results of the second survey led to recommendations to expand the training opportunities for National Park Service staff and for the development of paleontological resource protection training modules. An Albright-Wirth Grant was presented to the author in 1998 to coordinate the development of paleontological resource protection training with the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) and the National Park Service Horace Albright Training Center. Three paleontological resource training modules were produced through this collaboration and have been presented to more than 1,200 National Park Service employees.

Federal Paleontological Resource Crimes Investigation – Tyrannosaurus rex Specimen ‘Sue’

One of the most well-known fossils in the world is a Tyrannosaurus rex named ‘Sue’. This dinosaur skeleton is recognized as one of the largest, most complete and best-preserved specimens of the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex ever discovered and collected.

‘Sue’ was discovered during the summer of 1990 on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The complex story involving ‘Sue’ has become highly publicized, controversial, sometimes clouded by misinformation, and often overshadowed by the dinosaur. The discussion of the ‘Sue’ investigation is presented here based on the fact that there were ties to illegal fossil collecting in Badlands National Park and National Park Service staff participated in the investigation. The investigation led to the seizure of the dinosaur skeleton on May14,1992, followed by both civil and criminal litigation (Fiffer 2000). The civil litigation involving ‘Sue’ determined ownership of the fossil, and the specimen was eventually auctioned in October 1997 and sold for over $8 million dollars. Although the criminal portion of the case had almost nothing to do with the dinosaur ‘Sue’, media coverage has led to confusion about the criminal case by focusing on the dinosaur. In fact, the criminal portion of the case resulted in the first felony conviction for fossil theft through a trial in United States history. This portion of the case specifically involved catfish fossils stolen from Badlands National Park, an important historical fact which has largely been overshadowed by the media focus on the dinosaur.

California Desert Protection Act Recognizes Fossils at Two Parks

On October 31, 1994, the California Desert Protection Act was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. The law expanded the boundaries and redesignated two national monuments in California as national parks resulting in the establishment of Death Valley National Park and Joshua Tree National Park. The law referenced, for both national parks, the:

superlative natural, ecological, geological, archeological, paleontological, cultural, historical and wilderness values . . . (Public Law 103-433, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 410aaa et seq.).

Establishment of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Recognizes Fossils

On 11 January 2000, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, Arizona, was proclaimed by President Bill Clinton. According to the proclamation:

The monument is a geological treasure. Its Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rock layers are relatively undeformed and unobscured by vegetation, offering a clear view to understanding the geologic history of the Colorado Plateau . . . Fossils are abundant in the monument. Among these are large numbers of invertebrate fossils, including bryozoans and brachiopods located in the Calville Limestone of the Grand Wash Cliffs, and brachiopods, pelecypods, fenestrate bryozoa, and crinoid ossicles in the Toroweap and Kaibab formations of Whitmore Canyon. There are also sponges in nodules and pectenoid pelecypods throughout the Kaibab formation of Parashant Canyon. (Bill Clinton, Proclamation 7265).

Grand Canyon – Parashant National Monument includes lands which are administered by both the Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service.

Publication of the Secretary of Interior ‘Report to Congress’ – Fossils on Federal and Indian Lands

In May 2000, the Secretary of the Interior published a report titled Fossils on Federal and Indian Lands: Assessment of Fossil Management on Federal & Indian Lands. During the previous year Congress (Senate Appropriations Committee) requested information on the status and condition of paleontological resources and collections from federal lands in order to assess the need for a unified federal policy for fossils. In addition, during the previous two decades, a series of bills pertaining to paleontological resources were introduced to Congress, which resulted in some conflicting and confusing feedback from constituents. Eight consulting federal agencies participated in the development of the report to Congress including the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and U.S. Geological Survey. A draft report was developed and a notice regarding the report was published in the Federal Register. The draft report was presented at a public hearing and public comments were obtained which were incorporated into the final ‘Report to Congress’ published in May 2000.

Initiation and Completion of Fossil Resource Summaries for National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Networks

In order to better understand the scope, significance, distribution and management issues associated with National Park Service fossils, a strategy was established in 2001 to compile baseline paleontological resource data for parks. The strategy aligned with the recently created organization of the National Park Service into inventory and monitoring networks, a system in which 270 parks were grouped into 32 ecoregions based on similarities in natural resources. The Northern Colorado Plateau Inventory and Monitoring Network was selected as the prototype paleontological resource inventory network for the National Park Service (Koch and Santucci 2002). Between 2002 and 2012, paleontological resource inventories were systematically completed for all 32 National Park Service inventory and monitoring networks, expanding the number of parks identified with fossils from 135 in 1999 to 243 in 2014 (today there are 276 parks identified with fossils). The project also provided an excellent foundation for the ongoing National Park Service Paleontology Synthesis Project which compiles the bureau’s paleontological resource data by geologic time, taxonomy, museum repositories and other important data.

Petrified Forest National Park Expansion Act Adds Important Fossil Beds to Park

On December 3, 2004, President George W. Bush signed The Petrified Forest National Park Expansion Act of 2004 (Public Law 108-430, codified at 16 U.S.C. §§ 119) to authorize an expansion of the park boundaries identified in the park’s General Management Plan initiated during 1991. The park expansion more than doubled the size of the park, from 93,533 acres to 218,533 acres, which included highly fossiliferous Late Triassic deposits. Sections 4.6 and 6.8 of this paper provide additional historical information pertaining to Petrified Forest National Park. Also see Saving the Petrified Forest of Arizona (1865–1916) and Myrl Walker Promotes Paleontology at Petrified Forest National Monument (1916–1966).

First ‘Fossil Preparation and Collections Symposium’ Convened

In 2008, the Petrified Forest Museum Association hosted the first annual Fossil Preparation and Collections Symposium, an international conference that brought together 45 professional and avocational laboratory and collections specialists at Petrified Forest National Park. The success of this event led to increasingly larger meetings each year, eventually spawning the Association for Materials and Methods in Paleontology. Meetings sponsored by the Association for Materials and Methods in Paleontology have routinely featured strong National Park Service support, including hosting, collection tours, field trips, and continued participation from Petrified Forest National Park, Fossil Butte National Monument, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Dinosaur National Monument, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Waco Mammoth National Monument, and the National Park Service Museum Management Program (M. Brown, personal communication, 2017).

2009–Present

A New Beginning for NPS Fossils

Related Links

-

Badlands National Park (BADL), South Dakota—[BADL Geodiversity Atlas] [BADL Park Home] [BADL npshistory.com]

-

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve (BELA), Alaska—[BELA Geodiversity Atlas] [BELA Park Home] [BELA npshistory.com]

-

Big Bend National Park (BIBE), Texas—[BIBE Geodiversity Atlas] [BIBE Park Home] [BIBE npshistory.com]

-

Dinosaur National Monument (DINO), Colorado and Utah—[DINO Geodiversity Atlas] [DINO Park Home] [DINO npshistory.com]

-

Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument (FLFO), Colorado—[FLFO Geodiversity Atlas] [FLFO Park Home] [FLFO npshistory.com]

-

Fossil Butte National Monument (FOBU), Wyoming—[FOBU Geodiversity Atlas] [FOBU Park Home] [FOBU npshistory.com]

-

Guadalupe Mountains National Park (GUMO), Texas—[GUMO Geodiversity Atlas] [GUMO Park Home] [GUMO npshistory.com]

-

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument (HAFO), Idaho—[HAFO Geodiversity Atlas] [HAFO Park Home] [HAFO npshistory.com]

-

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (JODA), Oregon—[JODA Geodiversity Atlas] [JODA Park Home] [JODA npshistory.com]

-

Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO), Arizona—[PEFO Geodiversity Atlas] [PEFO Park Home] [PEFO npshistory.com]

-

Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve (YUCH), Alaska—[YUCH Geodiversity Atlas] [YUCH Park Home] [YUCH npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 27, 2023