History of Paleontology in the National Park Service—Santucci, V. L. (page 6 of 9)

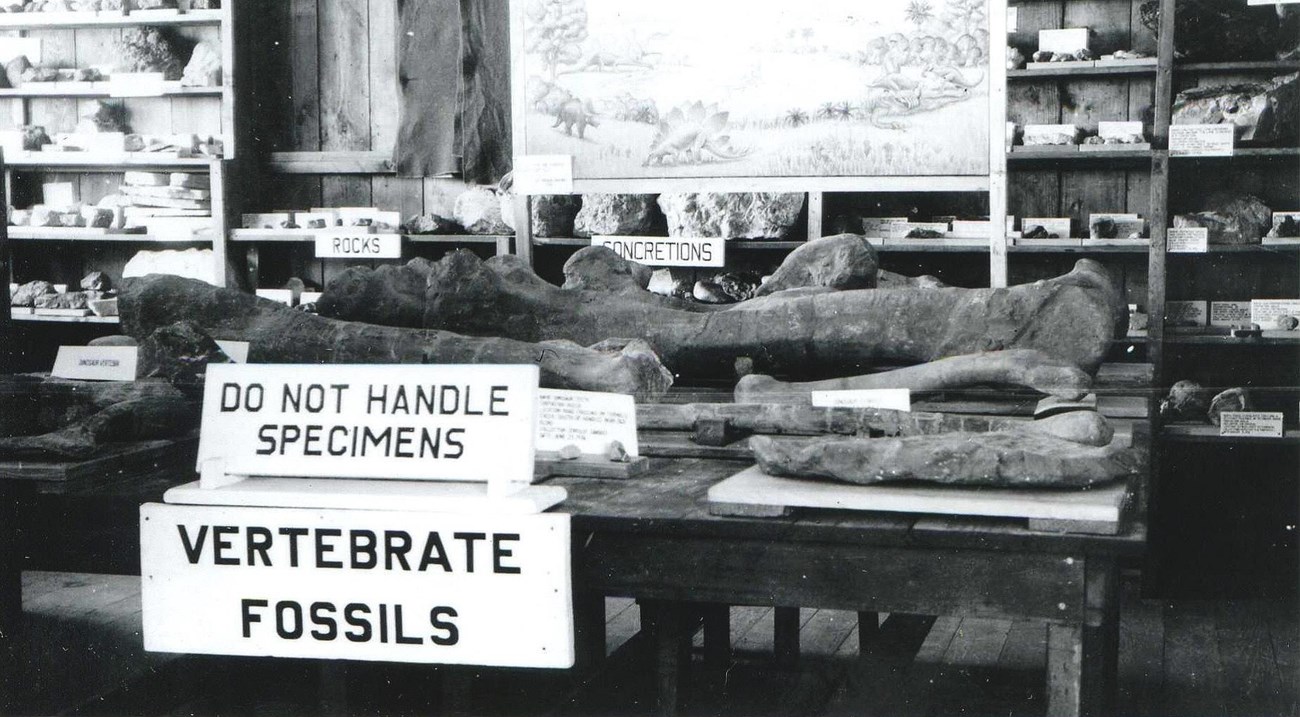

NPS photo.

Introduction

This historic period begins with the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 through the 50th anniversary of the bureau in 1966. The National Park Service Organic Act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on 25 August 1916, creating the National Park Service, as a new federal bureau in the Department of the Interior. The legislation included the following language which serves as the purpose of the National Park Service:

. . . to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations. (National Park Service Organic Act, 54 U.S.C. § 100101 et seq.).

In addition to the creation of the National Park Service and its first 50 years, this historic period included two world wars, the Great Depression and post-war globalization extending to the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service in 1966.

Establishment of Zion National Monument Recognized Fossils

On March 18, 1918, Zion National Monument, Utah, was proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson. According to the proclamation the significance of Zion was described by the following text:

The geologic features include craters of extinct volcanoes, fossiliferous deposits of unusual nature, and brilliantly colored strata of unique composition, among which are some believed to be the best representatives in the world of a rare type of sedimentation . . . the features of geographic interest include a labyrinth of remarkable canyons with highly ornate and beautifully colored walls, in which are plainly recorded the geologic events of past ages . . . (Woodrow Wilson, Proclamation 1435).

The monument was redesignated a national park on November 19, 1919 through a complex series of legislative actions.

Charles Sternberg Visits Chaco Canyon National Monument

During June 1921, the famous commercial fossil collector Charles Sternberg and his assistant John Bender visited Chaco Canyon National Monument (proclaimed in 1907). The monument was redesignated Chaco Culture National Historical Park in 1980. Sternberg discovered and collected some large fossil bivalves known as inoceramids. Sternberg unsuccessfully tried to sell the fossils to Dr. Carl Wiman at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. In a letter written by Sternberg to Dr. Wiman on July 11, 1921, referencing specimens for sale, he stated, “I found a fine locality at Pueblo Bonita [in the monument], where I got some fine Inoceramus shells” (Hunt et al. 1992, letter 2 appendix 1—Sternberg 1932). Wiman declined to purchase the shells as he apparently was only interested in vertebrate fossils.

Establishment and Deauthorization of Fossil Cycad National Monument

NPS photo.

On October 21, 1922, President Warren G. Harding proclaimed Fossil Cycad National Monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota (Proclamation 1641) as the third national monument established based on its fossil resources. The fossil locality preserved hundreds of Cretaceous cycadeoid specimens, possibly the world’s greatest concentrations of these fossil plants. Although established as a unit of the National Park Service, the monument was not actively managed. Years of negligent management at the monument resulted in irreparable impacts on the finite and scientifically significant paleobotanical resources. Fossils exposed on the monument’s surface were collected faster than erosion could expose other specimens from beneath. The loss of the exposed petrified plant remains eventually left the site devoid of fossils and ultimately without a purpose to justify its existence as a unit of the National Park Service. On September 1, 1957, the U.S. Congress voted to deauthorize Fossil Cycad National Monument (Santucci and Hughes 1998; Santucci and Ghist 2014).

Charles Gilmore Documents Fossil Vertebrate Tracks at Grand Canyon National Park

In 1924, the National Park Service invited Smithsonian paleontologist Charles Gilmore to examine Upper Paleozoic vertebrate tracks at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Gilmore documented and collected fossil tracks from the Wescogame Formation of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian), the Hermit Shale (Permian) and Coconino Sandstone (Permian). These fossil tracks were described by Gilmore in a series of publications during the late 1920s (Gilmore 1926, 1927, 1928). Gilmore also assisted with the design and construction of an in situ fossil track exhibit along the Hermit Trail which is no longer maintained.

Establishment of Badlands National Monument

After a decade-long effort, Badlands National Monument, South Dakota, was authorized on March 4, 1929 as a unit of the National Park Service. The authorizing act (Public Law 1021, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 441 - 441o) was signed by President Calvin Coolidge on the last day of his term as President of the United States. The area included in the monument preserved extremely fossiliferous strata from the Eocene and Oligocene epochs commonly referred to as the White River Badlands by early explorers and fossil collectors. The monument was not officially established until January 25, 1939 and was later redesignated as a national park in 1978. Also see Early fossil discoveries in the White River Badlands (1800–1865).

Paleontological Localities Evaluated as Potential National Monuments but Never Authorized

During the first 50 years of the National Park Service’s history, many natural and cultural areas were evaluated as potential national parks or monuments. The list of proposed new areas included a number of paleontological localities, such as: Mastodon National Monument, New Mexico; Red Rock Canyon (including the Petrified Cocoanut Grove) National Monument, California; States Red Mountain Coal Mine (dinosaur tracks) National Monument, Colorado; Glen Rose Dinosaur Tracksite National Monument, Texas; Irvington Fossil Deposit National Monument, California; Rancho La Brea (Tar Pits) National Monument, California; Sharktooth Hill National Monument, California; Gingko Petrified Forest National Monument, Washington; Esmeralda Petrified Forest National Monument, Nevada; and Calistoga Petrified Forest National Monument, California. Although these proposed fossil monuments were never authorized as National Park Service Areas, many would later be established as National Natural Landmarks.

Civilian Conservation Corps Supports Paleontology Projects in National Parks

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal included a public work relief program known as the Civilian Conservation Corps that existed between 1933 and 1942. The Civilian Conservation Corps was designed to create jobs during the Great Depression in the United States which involved the conservation and development of natural resources and it played an important role in the development of many early national parks and monuments (Paige 1985). Civilian Conservation Corps workers assisted with paleontology projects in several National Park Service areas including Badlands National Park, Big Bend National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Fossil Cycad National Monument and several other parks. The projects included the development of interpretive exhibits and support for fossil excavations, collection, and research.

Donald Curry and Fossil Discoveries at Death Valley National Monument

NPS photo.

On February 11, 1933, President Herbert Hoover, the only U.S. president formally trained as a geologist, proclaimed Death Valley as a national monument (Proclamation 2028). A year later in 1934, Donald Curry was hired as the first Ranger Naturalist at Death Valley National Monument. Curry is possibly the first professional geologist to wear the ranger uniform. He conducted geologic research during the day and presented interpretive programs to the public in the evenings. Curry is credited with the discovery of titanothere remains in Titus Canyon, fossil plant material from the Furnace Creek Formation, several new Tertiary fish fossils, and three fossil vertebrate track localities, most notably at the Copper Canyon tracksite. In his honor, two fossil species have been designated with the species name curryi including: Fundulus curryi (fish) and Protitanops curryi (mammal) (Santucci and Nyborg 1999).

Myrl Walker Promotes Paleontology at Petrified Forest National Monument

Between 1934 and 1938, Park Naturalist Myrl Walker was stationed at Petrified Forest National Monument. Although Walker was assigned to provide interpretation of park resources, he coordinated paleontological surveys, collected fossils, wrote reports, and even published a paper (Walker 1938) on some of the park fossils (Parker 2006). Walker was trained in paleontology and hosted Charles Gilmore and George Sternberg during field work in the park. Myrl Walker is considered to be the first paleontologist who worked for the National Park Service at Petrified Forest National Monument. Also see Saving the Petrified Forest of Arizona (1865–1916).

Establishment of Big Bend National Park and Early Fossil Discoveries

Between 1929 and 1936, Yellowstone Superintendent Roger Wolcott Toll would assist National Park Service Director Horace Albright during the winter months by evaluating proposed additions to the National Park System. During 1934, Toll traveled to the Big Bend region of Texas to visit the newly designated Texas State Park. In Toll’s Big Bend Trip Report, he described the “outstanding scenic area”. The recommendations made by Toll were instrumental in the June 20, 1935 authorization of Big Bend National Park by Congress as a unit of the National Park Service (Public Law 74-157, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 156 - 158). Within this legislation is specific language which references that the park will be established upon the conveyance of lands from the State of Texas to the federal government.

In February 1936, Toll and biologist George Melendez Wright visited Big Bend as participants in an International Park Commission to evaluate the area for possible designation of a transboundary park with Mexico. Tragically, on February 25, 1936, both Toll and Wright were killed in an automobile accident after their visit to Big Bend.

A young geologist named Ross Maxwell was hired by the National Park Service to survey the area of the proposed new national park. Maxwell and the Regional Geologist, Charles Gould, quickly recognized the important fossil vertebrates which occurred in the Cretaceous strata in the Big Bend area. Maxwell and Gould recruited help from the Civilian Conservation Corps to collect fossils and to construct a small museum in the Chisos Basin in a barracks at the Civilian Conservation Corps camp (Gould 1936). Unfortunately, a fire on December 24, 1941 destroyed the geology and fossil museum.

NPS photo.

A crew from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) helped to develop three fossil quarries in Big Bend during 1938 and 1939. The WPA crew worked under the supervision of William Strain from the Texas College of Mines and Mineralogy in El Paso, Texas. More than 500 fossil bones were collected under Strain’s supervision (Wick and Corrick 2015). The success of the WPA quarries drew several notable paleontologists into the field at Big Bend during 1940, including Charles Gilmore (Smithsonian) and Barnum Brown and Roland T. Bird (American Museum of Natural History). Brown and Bird collected a variety of dinosaur bones and partial jaws of the giant crocodilian which was later named Deinosuchus (Baird and Horner 1979).

A deed of conveyance was completed in 1944 and Big Bend National Park was officially established on June12, 1944, nine years after the authorization. Geologist Ross Maxwell was appointed the first superintendent and served from 1944 to 1952 (Maxwell 1985). During Maxwell’s tenure, he fostered a long-term relationship with paleontologists Wann Langston and Jack Wilson, and students from the Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin (later named the Texas Memorial Museum). Also see Fossils Discovered in the Big Bend Area (1865–1916).

Discovery of Fossils During the Construction of Boulder Dam

On October 13, 1936, Boulder Dam National Recreation Area (Public Law 88-639, codified at 16 U.S.C. §§ 460n – 460n-9) was established as a unit of the National Park Service to administer the reservoir lake and adjacent lands formed by the construction of Boulder Dam, known today as Hoover Dam. In 1947 the name was changed to Lake Mead National Recreation Area and was established as the first national recreation area in 1964. Geologist Edward Schenk was hired by the National Park Service to describe the geology and paleontology of the new recreation area. Schenk collected hundreds of fossil specimens from within, and around Lake Mead National Recreation Area. A portion of this collection is maintained in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area park museum collection. Some of Schenk’s fossil collection may have been sent to the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Virginia. A series of unpublished reports, prepared by Schenk regarding his work at Lake Mead during 1936 through 1938, are maintained in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area archives in Boulder City, Nevada (i.e. Schenk 1936, 1938).

Establishment of Channel Islands National Monument Recognizes Fossils

On April 26, 1938, Channel Islands National Monument, California, was proclaimed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (see Davis and Kimball 2017). According to the proclamation, the Channel Islands:

. . . lying off the coast of Southern California contain fossils of Pleistocene elephants and ancient trees, and furnish noteworthy examples of ancient volcanism, deposition, and active sea erosion, and have situated thereon various other objects of geological and scientific interest. (Franklin D. Roosevelt, Proclamation 2281).

The monument was designated a national park on March 5, 1989 (Public Law 96-199, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 410ff-410ff-7) and the islands of San Miguel, Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa were added to the park.

Discovery and Early Fossil Collecting at Rampart Cave

In April 1942, Remington Kellogg from the Smithsonian led a party, including members of the Civilian Conservation Corps, to Rampart Cave to excavate Pleistocene fossils. Rampart Cave is formed in the Cambrian Muav Limestone and was discovered in 1936 by National Park Service employee Willis Evans (Santucci et al. 2001). The cave preserved extensive deposits of Pleistocene ground sloth dung which contain the bones of ice age mammal fossils. Rampart Cave was originally within the boundaries of Lake Mead National Recreation Area, but was later incorporated into Grand Canyon National Park when that park’s boundaries were expanded in January 1975.

Commercial Development of the Petrified Forests of Florissant

By the 1920s, early discussions began about preservation of the Florissant Fossil Beds in Colorado, which had long been known to paleontologists and fossil collectors. Two privately owned petrified forest attractions existed at this time, less than a mile apart, and the owners eventually engaged in a competitive commercial rivalry resulting in a feud. The first was opened in 1890 under the name Coplen Petrified Forest and was later sold in 1926 to P. J. Singer. The name was changed to Colorado Petrified Forest in 1932. The second petrified forest, originally named the New Petrified Forest, was opened in 1920 and operated as a commercial quarry selling fossils. This operation changed its name initially to Henderson Petrified Forest and then to Pike Petrified Forest in 1950. The Pike Petrified Forest included the famous trio of petrified stumps and eventually closed to the public in 1961, but later was to be included within the boundaries of Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument (Leopold and Meyer 2012).

With permission of the The Walt Disney Company, © Disney.

While traveling in Colorado with his wife Lillian, cartoonist and producer Walt Disney visited the Pike Petrified Forest on July 11, 1956. Walt’s recognizable signature inscribed in the Pike Petrified Forest registry book for this day confirms his visit. The accounts of Disney’s visit to this tourist attraction vary slightly, but the important fact that Walt purchased a petrified stump that day is substantiated. The 7.5 foot (2.29 meters) tall Florissant stump can be viewed today on exhibit in Frontierland at Disneyland, California. One account associated with Disney’s purchase of the petrified stump suggests the fossil was purchased as a gift to his wife for their 31st wedding anniversary.

According to an interpretive sign with the petrified tree at the theme park, the specimen was presented to Disneyland by Mrs. Walt Disney in September 1957. However, in a letter dated July 19, 1956, from Walt Disney to Jack Baker, owner of the Pike Petrified Forest, the instructions were to deliver the petrified stump directly to Disneyland. Disney paid $1,650 for the stump and some smaller pieces of petrified wood.

Scientific Study of the Yellowstone Petrified Forests

Paleobotanist Erling Dorf and students from Princeton University conducted paleontological and geological field investigations in Yellowstone between 1955 and 1959 (Dorf 1960, 1964). This work involved mapping and field collection of plant fossils from a sequence of Eocene volcaniclastic deposits exposed along Specimen Ridge in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone. Dorf concluded there were at least 27 distinct petrified forests preserved at Specimen Ridge (Dorf 1964).

National Historic Landmarks and National Natural Landmarks Programs Established

In 1960 the National Park Service began to administer the National Historic Landmarks Program. The National Historic Landmarks Program supports the designation of nationally significant historic places by the Secretary of the Interior. National Historic Landmarks are sites and properties which possess exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. More than 2,500 historic places are designated as National Historic Landmarks, including five which are associated with famous paleontologists or historically important fossil localities.

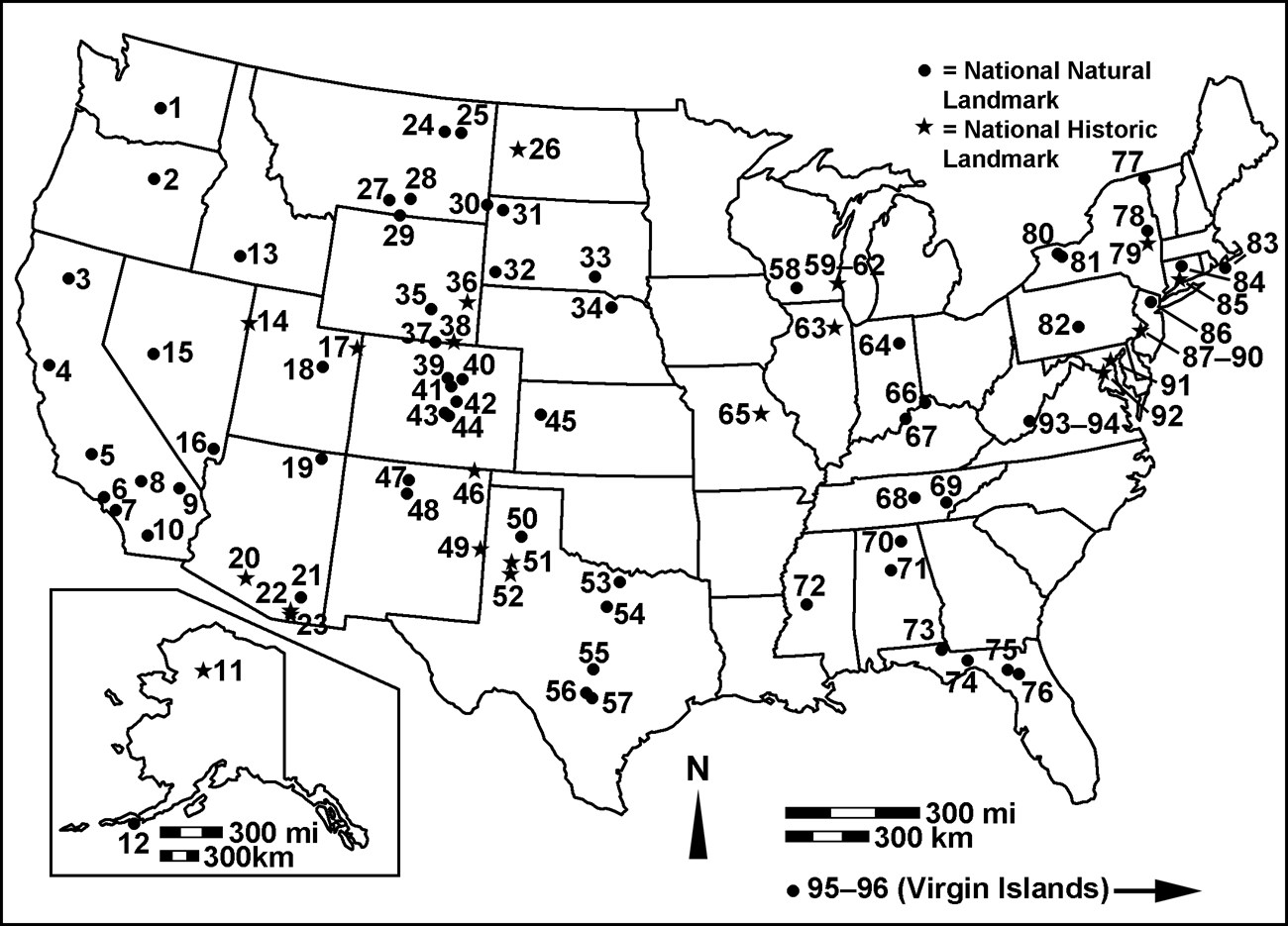

U.S. map showing the location of the 69 National Natural Landmarks (NNL) and 28 National Historic Landmarks (NHL) that are recognized based on the significant paleontological resources or history.

Source: NPS

1. Ginkgo Petrified Forest NNL, Washington

2. John Day Fossil Beds NNL (in JODA), Oregon

3. Lake Shasta Caverns NNL, California

4. Mount Diablo NNL, California

5. Sharktooth Hill NNL, California

6. Rancho La Brea NNL, California

7. Irvine Ranch NNL, California

8. Rainbow Basin NNL, California

9. Mitchell Caverns NNL, California

10. Anza-Borrego Desert State Park NNL, California

11. Onion Portage Archeological District NHL (in KOVA), Alaska

12. Unga Island NNL, Alaska

13. Hagerman Fauna Sites NNL (in HAFO), Idaho

14. Danger Cave NHL, Utah

15. Ichthyosaur Site NNL, Nevada

16. Valley of Fire NNL, Nevada

17. Quarry Visitor Center NHL (in DINO), Utah

18. Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry NNL, Utah

19. Comb Ridge NNL, Arizona

20. Ventana Cave NHL, Arizona

21. Willcox Playa NNL, Arizona

22. Murray Springs Clovis Site NHL, Arizona

23. Lehner Mammoth-Kill Site NHL, Arizona

24. Hell Creek Fossil Area NNL, Montana

25. Bug Creek Fossil Area NNL, Montana

26. Lynch Quarry Site NHL, North Dakota

27. Bridger Fossil Area NNL, Montana

28. Cloverly Formation Site NNL, Montana

29. Crooked Creek Natural Area NNL, Wyoming

30. Capitol Rock NNL, Montana

31. The Castles NNL, South Dakota

32. Mammoth Site of Hot Springs NNL, South Dakota

33. Bijou Hills NNL, South Dakota

34. Ashfall Fossil Beds NNL, Nebraska

35. Como Bluff NNL, Wyoming

36. Hell Gap Paleoindian Site NHL, Wyoming

37. Sand Creek NNL, Colorado and Wyoming

38. Lindenmeier Site NHL, Colorado

39. Morrison-Golden Fossil Areas NNL, Colorado

40. West Bijou Site NNL, Colorado

41. Roxborough State Park NNL, Colorado

42. Garden of the Gods NNL, Colorado

43. Garden Park Fossil Area NNL, Colorado

44. Indian Springs Trace Fossil Site NNL, Colorado

45. Monument Rocks NNL, Kansas

46. Folsom Site NHL, New Mexico

47. Ghost Ranch NNL, New Mexico

48. Valles Caldera NNL (in VALL), New Mexico

49. Blackwater Draw NHL, New Mexico

50. Palo Duro Canyon NNL, Texas

51. Plainview Site NHL, Texas

52. Lubbock Lake Site NHL, Texas

53. Greenwood Canyon NNL, Texas

54. Dinosaur Valley NNL, Texas

55. Longhorn Cavern NNL, Texas

56. Cave Without A Name NNL, Texas

57. Natural Bridge Caverns NNL, Texas

58. Cave of the Mounds NNL, Wisconsin

59. Dr. Fisk Holbrook Day House NHL, Wisconsin

60. Thomas A. Greene Memorial Museum NHL, Wisconsin

61. Schoonmaker Reef NHL, Wisconsin

62. Soldiers’ Home Reef NHL, Wisconsin

63. Mazon Creek Fossil Beds NHL, Illinois

64. Hanging Rock and Wabash Reef NNL, Indiana

65. Graham Cave NHL, Missouri

66. Big Bone Lick NNL, Kentucky

67. Ohio Coral Reef (Falls of the Ohio) NNL, Indiana and Kentucky

68. Big Bone Cave NNL, Tennessee

69. Lost Sea (Craighead Caverns) NNL, Tennessee

70. Cathedral Caverns NNL, Alabama

71. Red Mountain Expressway Cut NNL, Alabama

72. Mississippi Petrified Forest NNL, Mississippi

73. Florida Caverns Natural Area NNL, Florida

74. Wakulla Springs NNL, Florida

75. Ichetucknee Springs NNL, Florida

76. Devil’s Millhopper Geological State Park NNL, Florida

77. Chazy Fossil Reef NNL, Vermont

78. Petrified Gardens NNL (also Petrified Sea Gardens NHL), New York

79. James Hall Office NHL, New York

80. Fossil Coral Reef NNL, New York

81. Fall Brook Gorge NNL, New York

82. Bear Meadows Natural Area NNL, Pennsylvania

83. Gay Head Cliffs NNL, Massachusetts

84. Dinosaur Trackway NNL, Connecticut

85. Othniel Charles Marsh House NHL, Connecticut

86. Riker Hill Fossil Site NNL, New Jersey

87. Charles Willson Peale NHL, Pennsylvania

88. Edward Drinker Cope House NHL, Pennsylvania

89. Hadrosaurus Foulki Leidy Site NHL, New Jersey

90. Wagner Free Institute of Science NHL, Pennsylvania

91. Peale’s Baltimore Museum NHL, Maryland

92. David White House NHL, District of Columbia

93. Organ Cave System NNL, West Virginia

94. Lost World Caverns NNL, West Virginia

95. Coki Point Cliffs NNL, Virgin Islands (St. Thomas)

A similar natural resource-focused program is the National Natural Landmarks Program which was established on May 18, 1962 by Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall (see Eggleston and Connors 2017). The program is administered by the National Park Service and promotes conservation and voluntary preservation of outstanding natural resources. A thematic inventory of ecological and geological sites throughout the United States was conducted between 1970 and 1987, including an inventory of significant Mesozoic fossil vertebrate sites for possible inclusion in the National Natural Landmarks Program (Ostrom 1985). As of the date of this publication, 45 National Natural Landmarks were established primarily based on their significant paleontological resources.

A Really ‘Big Dig’ at Tule Spring Fossil Beds

Between October 1962 and February 1963, a team of geologists, paleontologists and archeologists converged in an area north of Las Vegas known as Tule Springs. This scientific undertaking, later referred to as the ‘Big Dig’, was an intensive effort to find evidence suggesting early humans and ice age mammals co-existed along the Las Vegas Wash during the Late Pleistocene. The first remains of extinct mammoths, camels, bison, sloths and horses were discovered at Tule Springs several decades earlier. The documentation of charcoal and the discovery of a few potentially ‘human modified’ objects presented hope that Tule Springs may shed light on the discussion of human antiquity in North America.

The expedition at Tule Springs was led by geologist C. Vance Haynes from the University of Arizona (Wormington and Ellis 1967). The scientific team included Willard Libby from the University of California at Los Angeles who was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his pioneering work on radiocarbon dating. Libby’s analysis of Carbon 14 (14C) samples from Tule Springs represented the first field testing of his new age-dating technique. Although the results of the ‘Big Dig’ were not able to conclusively determine the co-existence of humans and ice age megafauna, the significance of the Late Pleistocene fossil locality resulted in the area being designated as the Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument approximately 50 years after the ‘Big Dig’.

Resdesignation of Petrified Forest National Monument to National Park

On December 9, 1962, Congress established Petrified Forest National Park by redesignating and expanding the 1906 national monument. The original park legislation (Public Law 85-358) was first approved by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1958, but President John F. Kennedy signed the final legislation in 1962. Also see Congress authorizes the Antiquities Act (1865–1916) and Donald Curry and fossil discoveries at Death Valley National Monument (1916–1966).

Authorization of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument

On June 5, 1965, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska, was created as a unit of the National Park Service. According to the enabling legislation, the monument was created

. . . to preserve for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations the outstanding paleontological sites known as the Agate Springs Fossil Quarries, and nearby related geological phenomena, to provide a center for continuing paleontological research and for the display and interpretation of the scientific specimens uncovered at such sites, and to facilitate the protection and exhibition of a valuable collection of Native American artifacts and relics that are representative of an import phase of Native American history. (Public Law 89-33).

Although the monument was authorized in 1965, it was not established until June 14, 1997. Also see Investigation of the Bone Bed at Agate Ranch (1865–1916).

1966–2008

Filling Gaps in the Fossil Record

Related Links

-

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (AGFO), Nebraska—[AGFO Geodiversity Atlas] [AGFO Park Home] [AGFO npshistory.com]

-

Badlands National Park (BADL), South Dakota—[BADL Geodiversity Atlas] [BADL Park Home] [BADL npshistory.com]

-

Big Bend National Park (BIBE), Texas—[BIBE Geodiversity Atlas] [BIBE Park Home] [BIBE npshistory.com]

-

Chaco Culture National Historical Park (CHCU), New Mexico—[CHCU Geodiversity Atlas] [CHCU Park Home] [CHCU npshistory.com]

-

Channel Islands National Park (CHIS), California—[CHIS Geodiversity Atlas] [CHIS Park Home] [CHIS npshistory.com]

-

Death Valley National Park (DEVA), California and Nevada—[DEVA Geodiversity Atlas] [DEVA Park Home] [DEVA npshistory.com]

-

Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument (FLFO), Colorado—[FLFO Geodiversity Atlas] [FLFO Park Home] [FLFO npshistory.com]

-

Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), Arizona—[GRCA Geodiversity Atlas] [GRCA Park Home] [GRCA npshistory.com]

-

Lake Mead National Recreation Area (LAKE), Arizona and Nevada—[LAKE Geodiversity Atlas] [LAKE Park Home] [LAKE npshistory.com]

-

Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO), Arizona—[PEFO Geodiversity Atlas] [PEFO Park Home] [PEFO npshistory.com]

-

Yellowstone National Park (YELL), ID, MT, and WY—[YELL Geodiversity Atlas] [YELL Park Home] [YELL npshistory.com]

-

Zion National Park (ZION), Utah—[ZION Geodiversity Atlas] [ZION Park Home] [ZION npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 27, 2023