|

Although known for its vast natural landscapes, the Everglades have been home and hunting grounds for many people and groups. Since the emergence of the River of Grass, Native Americans and later on Anglo-American settlers known as “Gladesmen” traversed the wild landscape and came to rely on its abundant natural resources, and explore its mysteries. Developers would make their mark on the land in a different way, by seeking to alter the wetland landscape by draining the land and building roads and canals. In response to the rapid alterations which were affecting the Everglades, Conservation groups like the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs pioneered efforts to reclaim and save the “River of Grass” from further development. Learn more about the people that have lived and worked in the Everglades.

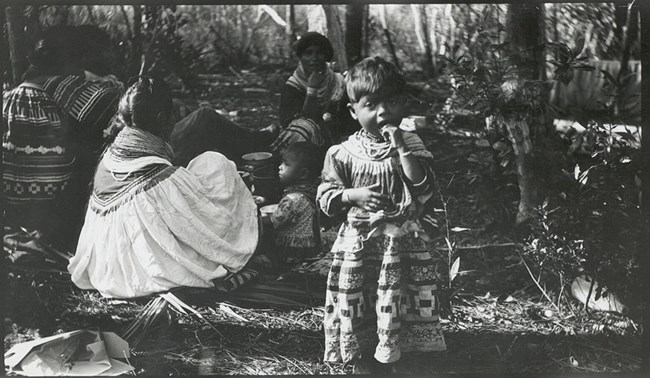

NPS (EVER 17420) Before the Spanish arrived in 1513, the region in south Florida that is now the Everglades National Park was largely inhabited by the Calusa Indians. Emerging around 1000 B.C., the Calusa maintained a highly organized society, and left behind many traces of their civilization, including large scale architectural shell works, shell tools, carved wood, and long distance canoe trails. By the 1700s most of the Calusa population had been decimated by the incoming disease brought by settlers. With the demise of indigenous people in south Florida, and white settlement occurring to the north, increasing migrations of Creek peoples were forced southward for hunting and settling. The Seminole and Miccosukee, tribes affiliated with the Creek federation, were in the area as early as the eighteenth century.

Florida Memory Project Early colonial settlers and land developers viewed the Everglades as a worthless swamp in need of reclamation. The dream of draining the swampland took hold in the first half of the 1800s. By the 1880s developers started digging drainage canals, which took place without an understanding of the dynamics of the ecosystem and were generally inadequate for the task. Their actions caused localized silting problems, but overall the ecosystem was resilient enough to sustain itself.

NPS (EVER 12140) At the end of the nineteenth century the south Florida coast was still largely wilderness, one of the last coastal regions east of the Mississippi to be settled. Only three small communities -- Chokoloskee, Cape Sable and Flamingo -- existed along the coast of what is now Everglades National Park. These isolated locations, far removed from large developed centers, attracted those adjusted to independently living off of the land. The only way to arrive at Flamingo or Chokoloskee was by boat. Supplies were shipped from Key West, Fort Meyers or Tampa and cane syrup, fish, and produce were traded in return. Although the communities were never to become a metropolis, they did have commerce, with some vegetables from Chokoloskee even reaching New York City.

NPS (EVER 22013) Before the Everglades was established as a National Park in 1947, many people made their living off of the land. Often known as “Gladesmen,” these were men thoroughly experienced with the land who hunted, camped, and survived off the everglades. The culture of the Gladesmen has developed around this unique relationship with the land, which they depended upon for their survival. The Gladesmen depended upon the land and its resources to meet their basic needs, as well as providing individual and community fulfillment.

NPS Florida Federation of Women's Clubs The Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs, established in 1895, was an umbrella organization for the many state women’s groups that existed. By 1922, membership of FFWC reached 12,000 women. The women’s clubs organized around issues such as prohibition, education, voting rights, rights for the ill, and conservation. The work of these women led to numerous local and statewide reforms and laws. May Mann Jennings, president of the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs and wife of Florida governor W. S. Jennings, led conservation efforts in south Florida. Her work led to the establishment of Royal Palm National Park, which was managed by the FFWC until 1947 when it was incorporated by Everglades National Park. Well known for her oratory skills and leadership on a range of issues, May Mann Jennings became one of Florida’s most celebrated activists.

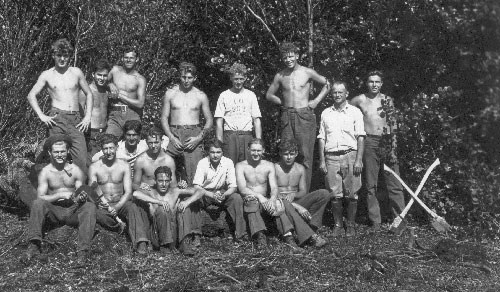

University of Florida library. Civilian Conservation Corps The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began in April 1933 and sprouted from FDR’s New Deal Plan as an effort to employ low income youth to complete conservation work on the nation’s various state and national parks. Civilian Conservation Corps members received $30 a month, $25 of which was sent back home to their families. The Civilian Conservation Corps operated a number of companies until it ended in 1941, in order to devote more funding to war efforts. From October 1933-June 1934 Civilian Conservation Corps Company 262 completed trail work, planted trees, constructed telephone lines, repaired storm damaged structures, and completed other tasks for Royal Palm State Park (Florida SP-1). |

Last updated: January 10, 2021