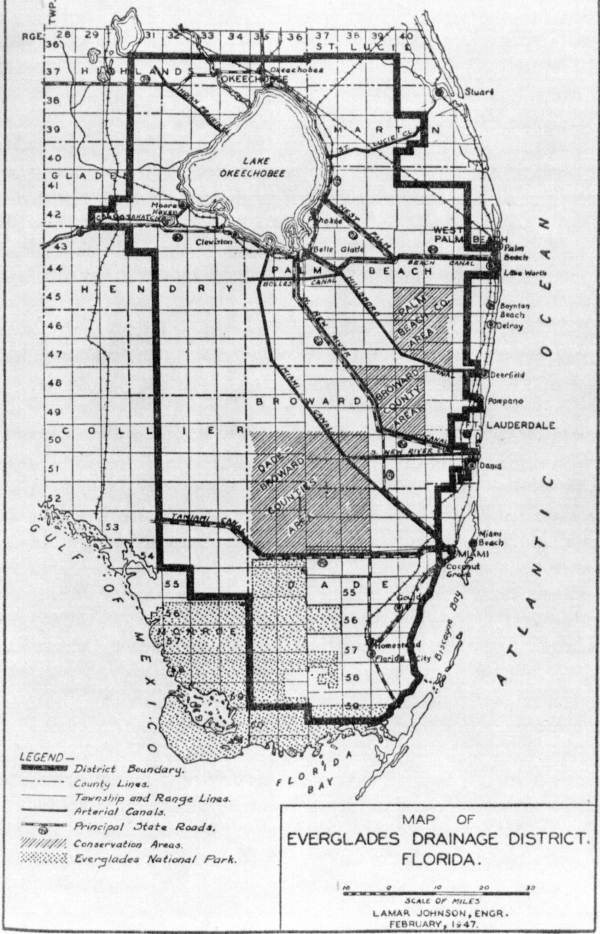

Florida Memory project Draining the Everglades The notion of draining the vast wetland persisted into the 20th century. Expanded dredging efforts between 1905 and 1910 transformed large tracts from wetland to agricultural land. This abundance of "new" land stimulated the first of several south Florida land booms. Railroads constructed by entrepreneurs like Henry B. Plant and Henry M. Flagler made the region more accessible and attractive to tourists. By the 1920s visitors and new residents flocked to blossoming towns like Fort Lauderdale, Miami, and Fort Myers. As they arrived, developers cut more canals and built new roads. To ensure good ocean views, they removed mangroves from the shorelines and replaced them with palm trees. Little by little canals, roads, and buildings displaced native habitats. The year 1948 marked an even greater change when Congress authorized the Central and South Florida Project. This involved the construction of an elaborate system of roads, canals, levees, and water-control structures stretching throughout South Florida. Constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers, and sponsored by the Central and Southern Flood Control District (later redesignated the South Florida Water Management District), the project purposes were to provide water and flood protection for urban and agricultural lands, a water supply for Everglades National Park, the preservation of fish and wildlife habitat, facilitate navigation and recreation, and the prevention of salt water intrusion. While the project still provides many of the intended benefits, the alteration of regional wetland areas, estuaries, and bays — combined with increasing population pressures and changing land uses — has significantly degraded the natural system.

Florida Memory Project Early Communities By 1910, approximately 50 people lived in Flamingo and Cape Sable. Census records from that year reveal that many of the African Americans living in Flamingo were born in the Bahamas and Jamaica. Life in Flamingo could be unpleasant. Leverett White Brownell, a naturalist, visited Flamingo in 1893. He described the village as 38 shacks on stilts, infested with fleas and mosquitos. He claimed to have seen an oil lamp extinguished by a cloud of mosquitoes. He also stated the flea powder was the “staff of life” and that the cabins were thickly sooted from the use of smudge pots. He added that tomatoes, asparagus, and eggplant were the principle crops.

NPS EVER 15022 Chokoloskee, near present-day Everglades City, was first settled in the 1870s, although it had been the home of Calusa Indians for centuries in pre-Columbian times. It became the trade center for homesteaders who occupied the deserted Calusa sites scattered throughout the Ten Thousand Islands region. Over 140 people occupied Chokoloskee in 1910. Like Flamingo and Cape Sable, most were farmers or laborers. In addition to the general unpleasantness that life in Everglades could bring, hurricanes were another challenge that early settlers had to contend with. The Everglades and Chokoloskee community was just recovering from a hurricane in 1909 when it was devastated by another, the worst on record, the following year. Only the highest ground of the old Calusa shell mound remained above water. Low-lying farm fields were salted by flood tides and most cisterns were polluted, a major tragedy in an area where few springs or wells existed. Many inhabitants of the outlying islands were forced to abandon their homesteads. The most infamous incident of the times, the vigilante murder of a local man suspected of several murders, occurred a few days after the hurricane. A fictionalized account of the event is told in the book Killing Mister Watson by Peter Matthiesson.

NPS (EVER 17324) Prosperity of a sort reached Everglades City in the 1920s when Barron Collier made it his headquarters for the building of the Tamiami Trail across south Florida. It served as the county seat of Collier County until 1960, when prosperity waned and county offices were moved to Naples. Neighboring Chokoloskee did not have a road until a causeway was built from the mainland in 1956. Flamingo, still marking the end of the main park road, is now a park community with a campground, ranger station, marina and lodge. Chokoloskee, surrounded by park waters at the end of Highway 29, is still home to fishermen, with a few motels and a resort having been added for park visitors. Although the tiny cane farms and fishing shanties are gone, both areas maintain the tranquil beauty for which they are famous. |

Last updated: June 20, 2020