|

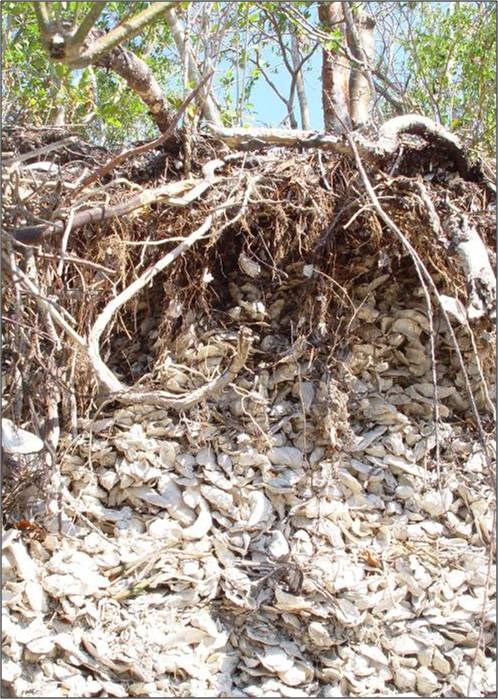

Shell Works The Calusa tribe occupied a large area of the Southwest coast of Florida from the area west of Lake Okeechobee down to Cape Sable. The tribe was organized as a Chiefdom and was composed of many small villages, each containing a chief. Many of these villages were located along the 10,000 islands. This coastal group utilized the resources around them for subsistence. They depended mostly on fishing and some strategic foraging for foodstuffs. Their tools were made from shells, and other resources that could be found and manipulated. Tools such as hammers, picks, and scrapers were made by creating small holes in conch, clam, and oyster shells and placing a stick within to form a handle. These were used for digging, hammering, picking, fishing, and performing other tasks. Fish bone and shark teeth were also utilized to create tools. Additionally, shells were used for making jewelry, ornaments. The discarded tools and leftover shells emptied of foodstuffs were piled to create shell works. Shell works are large-scale, planned formations of piled oyster shells that formed built villages. It is unknown what their primary purpose may have been, but archaeologists suggest that the shell works separated domestic and public from sacred spaces. Shell deposits were formed to create high ridges, mounds, crescents, platforms, canals and courtyards. According to William Morgan, author of Precolumbian Architecture in Eastern North America, these works created networks linking communities and resources, as well as dividing separate zones of space.

NPS Shell works were a collection of shell middens, earthen mounds, and other shell or earthen work accumulations. Shell middens were formed over time from discarded shells that were left to collect over generations. After time, ridges would develop in the middens, creating rows of large mounds in a village. These same efforts were utilized to create platform mounds to build houses and community space. Canals leading from the shoreline were often created to link directly to the villages or even to a chief’s platform. The large scale formations suggest they would have required organization and planning of many workers to construct. Archaeologists believe shell works may have been present in the Everglades from the late archaic to the 16th century Calusa Indian villages (1000 BC – 1500 AD). Shell works and other residue of past material culture can still be found in the Everglades today.

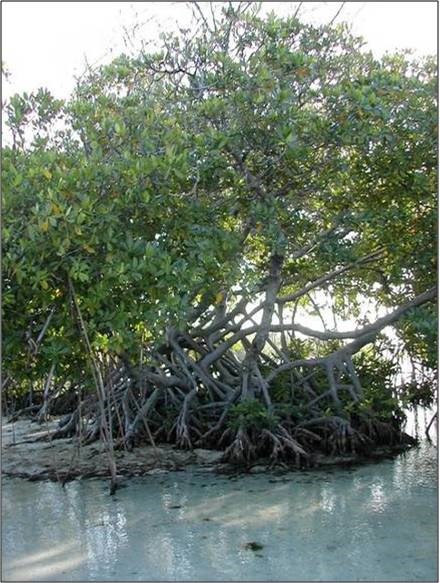

NPS Tree Islands As a subtropical preserve, the Everglades hosts a unique mix of ecosystems and plant communities. Temperate and tropical zones result in a mix of saw grass prairies, mangrove and cypress swamps, pinelands, hardwood hammocks, as well as marine and estuarine elements. The occurrence of these subsystems is dependent upon elevation, water levels, and the presence or absence of fire. The term “Tree Island” refers to a naturally formed small patch of forest settled in a marsh that resembles an island of trees from afar. Tree Islands in the Everglades are composed of hardwood trees, palms, ferns, and a variety of tropical plant species in areas of raised vegetation. They also often occur in hammocks, land that is slightly higher than the surrounding marshes and prairies. Generally, these islands resemble a tear drop shape because of the flow of water that occurred before the Everglades were drained. Tree Islands were significant places for native peoples of the Everglades. Archaeologists have found that tree islands almost always contain archaeological remains, and in some cases, Tree Islands may be present because of archeological remains. Soil intermixed with dense concentrations of animal bones and shards of ceramic, shell, and other debris are archeological materials that are often found. The existence of this material suggests that native people were also maintaining inland central settlements. As the Tree Islands are the only areas that historically stayed dry during the wet season, many were also used by the Seminole and Miccosukee. Many also continue to be maintained as hunting camps by “Gladesmen” and airboat operators in the East Everglades section of the Park.

NPS Mud Lake Canal Beyond shell tools and shell mounds, native people have also left behind clues of their manipulation of the land in the construction of long distance canal systems. The discovery of an intact canoe canal offers an example of the engineering and organization utilized by native peoples. The Mud lake Canal is a well preserved aboriginal canoe canal that is 3.9 miles in length. The canal is unique in both its design and purpose. The canal acted as a major hub for canoe travel between the Everglades, Ten Thousand Islands, and the Florida Keys during prehistoric times. This pivotal location allowed native people to travel from the Ten Thousand Islands to the Bay of Florida without traveling through the rough waters in the Gulf of America. Construction of the canal would have required major labor and organization. The canal extends 20-30 ft across and is 1-2 feet deep, connecting bodies of water that are not of the same elevation. It stretches through marl prairies and mangroves The canal is associated with the Bear Lake Mound group, a site attributed to a Tequesta village. Mud Lake Canal feeds into a group of mounds that once accommodated a small village with 20-50 people. Carbon dating from the canal bed sediments suggests that the canal was built during the Glades II period (AD 750-1200). The Mud Lake Canal was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 2006 as one of only a handful of surviving preshistoric canoe trails in North America. |

Last updated: February 14, 2025