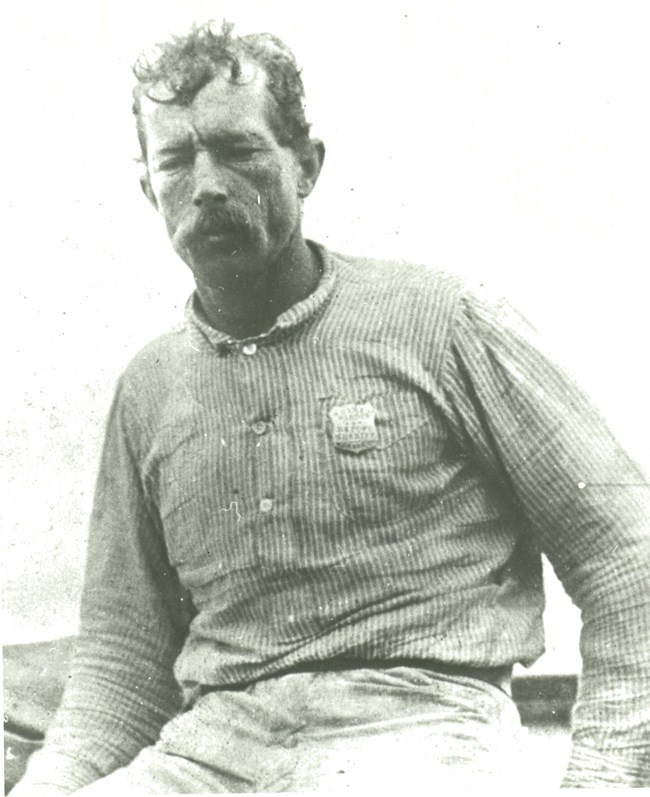

NPS Central Figures to Conservation The harmful side effects of dredging and draining the Everglades were apparent early in 20th century. Before the Everglades was established as a National Park, the conservation movement inspired some protection of the area’s fauna. Florida Governor Jennings, with help from the Florida Audubon society, instituted a ban on plume hunting in 1900. The Audubon Society hired Flamingo native Guy Bradley as a bird warden for the area surrounding the Everglades. Bradley was well known for his love of nature and never responded kindly to poachers and hunters in the area. Taking his job very seriously, Bradley issued citations and arrested violators of the recent plume ban. With the number of game hunters who depended upon the Everglades for survival, Bradley’s enforcement of the law would eventually bring a conflict that ended in his murder. In 1905, Bradley arrested the son of a local hunter who he had caught plume hunting for the third time. The boy’s father, who promised to shoot Bradley if he arrested his son again, shot and killed Bradley. The death of Guy Bradley, an early conservationist, marked the discord between the local community and conservation efforts that would continue.

NPS In 1928 landscape architect Ernest Coe began a concentrated effort to designate a "Tropical Everglades National Park." His persistence paid off when he and others persuaded Congress to designate the Everglades as a national park in 1934. It took park supporters another 13 years to acquire land and secure funding. In 1947, Marjory Stoneman Douglas would publish The Everglades: River of Grass, a work that would come to greatly influence the public perception of the oft-misunderstood region. That same year, Everglades National Park officially opened, marking the first large-scale attempt to protect the area's unique biology. Today, the park comprises a vast wetland wilderness unlike any other in the world. |

Last updated: April 14, 2015