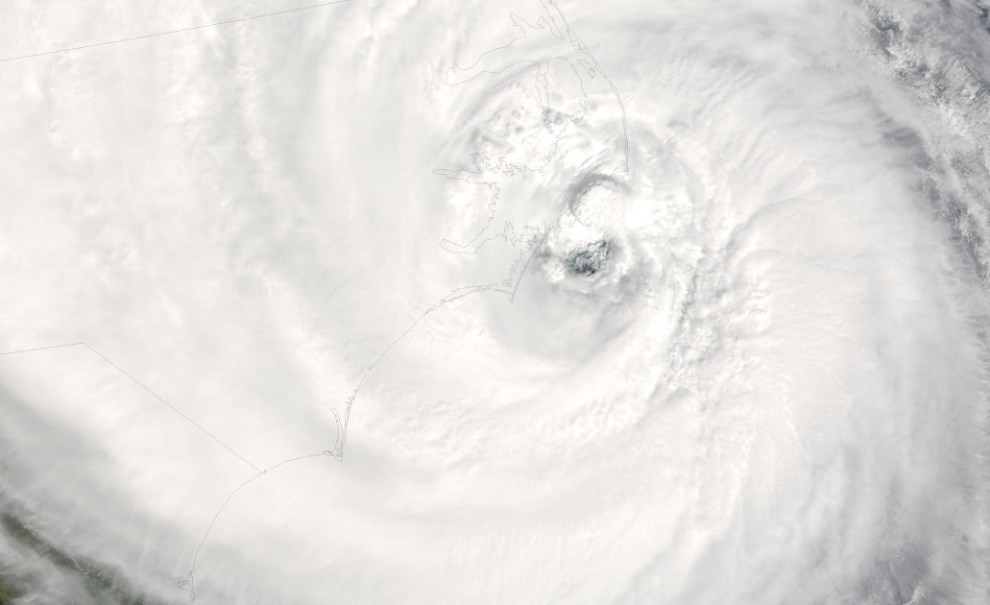

NASA image by Jacques Descloitres, MODIS

To highlight the National Park Service’s management response to storms, let’s consider Hurricane Isabel (2003), a category 2 storm. This example is interesting because the same storm in the same area resulted in two very different responses in two very different national seashores. Although Hurricane Isabel affected a number of National Park System units—Colonial National Historical Park, Richmond National Battlefield Park, Petersburg National Battlefield, George Washington Birthplace National Monument, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields National Military Park, Shenandoah National Park, and George Washington Memorial Parkway in Virginia; Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park in Maryland; National Capital Parks in Washington, D.C.; and Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site in Pennsylvania—this tropical cyclone made landfall along Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout national seashores on 18 September 2003. Most work within the National Park Service focused on these two national seashores, and 172 people responded to the incident (National Park Service 2004). The eye of the storm passed near New Drum Inlet within Cape Lookout. The northeast quadrant of the storm, where the destructive forces are typically at their maximum, passed over the southern section of Cape Hatteras (York 2004). At Cape Hatteras Pier, sustained winds reached 78 miles per hour (126 kph) with peak gusts of 96 miles per hour (154 kph). Storm surge reached 7.7 feet (2.3 m) at this location (National Park Service 2004).

NASA image by Mike Trenchard, JSC

Hurricane Isabel, NASA, Jacques Descloitres, MODIS

Hurricane Isabel was directly responsible for 16 deaths and indirectly responsible for another 34 deaths. The hurricane caused widespread wind and storm-surge damage in coastal eastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia. Storm-surge damage also occurred along Chesapeake Bay and the associated river estuaries, while wind damage occurred over portions of the remaining area from southern Virginia northward to New York. The estimate for insured property damage came to $1.685 billion. Estimates at specific parks include $28 million at Cape Hatteras National Seashore and $17 million at Cape Lookout National Seashore (National Park Service 2004).

At Cape Lookout, almost every boat dock and ramp was lost. Portsmouth Village sustained extensive damage from storm surge, and infrastructure throughout the park (except for Harkers Island) was seriously damaged. Two concession operations sustained extensive damage. Other damage included the destruction of water systems, 40 septic systems, the park’s solar energy/generator systems, and 40 private vehicles (National Park Service 2004). At Cape Hatteras, sections of Highway 12—the only transportation corridor for Hatteras and Ocracoke islands—were covered with deep sand in some place and completely washed away in other places. Campground facilities and docks were damaged, the Bodie Island maintenance shop lost a third of its roof, two parking lots washed away, and about two-thirds of the pony pen fencing was either damage or washed away (National Park Service 2004).

NPS photo by Mark Borrelli.

NPS photo by Mark Borrelli.

A primary component of the National Park Service’s mission is to provide for the enjoyment of the American people (but only to the extent that such enjoyment does not impair resources). Therefore, restoring visitor access after storms is a high priority. Restoring visitor access in Cape Hatteras National Seashore after Hurricane Isabel equated to major highway reconstruction, including removal and placement of sand and repair of damaged asphalt. By contrast, restoring visitor access in Cape Lookout National Seashore equated to remarking the unpaved road and beach-access ramps on top of the newly deposited sand, as well as rebuilding docks. Therefore, although both parks experienced wind, wave, overwash, and storm surge, “the difference in form and extent of infrastructure led to different restoration effort for each park” (York 2004).

One example of the contrast in restoration efforts between the two seashores is the response to overwash. In Cape Lookout National Seashore, washover channels and fans created during Hurricane Isabel were allowed to remain in their natural state, thereby preserving part of the barrier-island evolution process. By contrast, washover deposits left Highway 12 impassable in many stretches within Cape Hatteras National Seashore, and the North Carolina Department of Transportation cleared the road of sand and repaired road damage. However, unnatural clearing and placement of sand (on the ocean side of the road) effectively stops the overwash process, ultimately threatening the survival of the barrier island to evolve with sea level rise (York 2004).

Another restoration contrast between the two national seashores pertains to inlet formation. Although an inlet did not form within Cape Lookout National Seashore during Hurricane Isabel, numerous inlets have opened, migrated, and closed in this barrier island chain throughout history. Since the 1970s, resource management at Cape Lookout has allowed inlets along the Core Banks to evolve through natural processes (York 2004). By contrast, at Cape Hatteras National Seashore an inlet north of Hatteras Village opened during Hurricane Isabel, reoccupying a site of a former inlet that closed in the 1930s by natural processes (Wamsley and Hathaway 2004). According to York (2004), “formation of the new inlet severed Highway 12, the principal transportation link of the residents of Hatteras Village to other island villages and the mainland. Without other means of access such as bridge, causeway, or ferry immediately available to the villagers, the situation was considered an emergency. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers filled the inlet under direction of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Wutkowski 2004). The North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) reconstructed the highway once the inlet was filled.”

NPS photo.

NPS photo.

Another restoration contrast between the two national seashores pertains to inlet formation. Although an inlet did not form within Cape Lookout National Seashore during Hurricane Isabel, numerous inlets have opened, migrated, and closed in this barrier island chain throughout history. Since the 1970s, resource management at Cape Lookout has allowed inlets along the Core Banks to evolve through natural processes (York 2004). By contrast, at Cape Hatteras National Seashore an inlet north of Hatteras Village opened during Hurricane Isabel, reoccupying a site of a former inlet that closed in the 1930s by natural processes (Wamsley and Hathaway 2004). According to York (2004), “formation of the new inlet severed Highway 12, the principal transportation link of the residents of Hatteras Village to other island villages and the mainland. Without other means of access such as bridge, causeway, or ferry immediately available to the villagers, the situation was considered an emergency. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers filled the inlet under direction of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Wutkowski 2004). The North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) reconstructed the highway once the inlet was filled.”

Related Links

Last updated: July 16, 2019