Robert J. Sporleder photo album 1896 The Pecos High Bridge may be the most famous of all the historic bridges in Texas. In 1892, it held the distinction of being not only the highest bridge in the United States, but also, at 322 feet 10 3/4 inches in height, the third highest bridge in the world. Strengthened in 1910 and 1929, this bridge was in continuous service as part of the nation's first southern transcontinental railroad until it was replaced by a newer one during World War II. Known to railway historians as the Pecos Viaduct, this bridge was the second across the Pecos and was designed to solve a host of problems that had plagued the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway since the line opened in 1883. The track winding down into and out of the canyon to the first bridge left the flat uplands 5-6 miles distant from either side of the bridge. Following the sinuous canyon rim in a series of curvy and steep grades crossing numerous deep intervening side canyons, the track descended to the bridge. In some sections the grade consisted of no more than a narrow ledge blasted into the towering cliff walls. So prone were these to rock falls that the railway company had to employ "track-walkers" both night and day to prevent derailments caused by obstacles on the road bed.

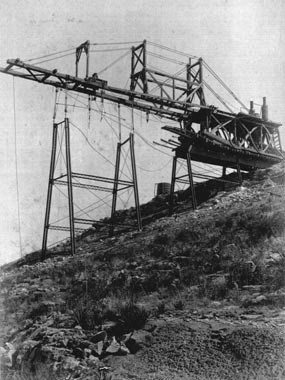

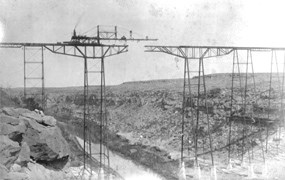

Courtesy Lehigh University By February, 1891, Ricker, Lee, and Company received the contract for pier and footer construction and for building the approaching grading to the new bridge. The piers supporting the bridge were made from concrete and local limestone cut from the canyon bottom and floated into place. Seven of the most important footings had copings cut from Texas pink granite from the Granite Mountain Quarry in Burnet County more than 200 miles from the construction site. All piers and footings were constructed on bedrock. It was often difficult for the engineers to determine exactly its location due to the accumulations of river deposits and boulders in the bottom of the canyon. Pier number nine was the most difficult to construct because of these deposits. Although the pier was 55 feet in overall height, only about five feet of it was visible at the surface. By the end of October 1891, the footers and piers were completed: Ricker, Lee, and Company then turned their attention to constructing the grades and new track leading to the east and west sides of the canyon rim. The Phoenix Bridge Company of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania began work on the bridge's iron and steel towers and spans on November 3, 1891, under the direction of Chief Engineer J. T. Mahl. No heavy locomotive cranes existed at this time, so engineers designed an apparatus called a "traveler" to lower the heavy iron beams into place. This strange looking device (Figure 2) utilized an overhanging arm that was 124.6 feet in length, greater than any traveler ever used before (Wilson 1925:29), to lower bridge sections into place. This arm was counter-balanced by the 57 foot wheelbase of the traveler, clamped to the completed section of bridge during operation. The various sections of bridgeworks were assembled on both sides of the river adjacent to the track and then lowered into place by the traveler. The bridge sections included two cantilever arms, 85 feet in length; four tower spans, each 35 feet in length; two lever arms, 52.6 feet in length; one suspended lattice span, 80 feet in length; eight lattice spans, 65 feet in length; one plate girder span, 45 feet in length; and 34 plate girder spans, each 35 feet in length (ibid).

Courtesy Whitehead Museum The traveler began work from the east canyon rim lowering sections of bridgeworks down into the canyon. When the machine reached the approximate mid-point of the future bridge, it backed up and returned to the east canyon rim, was dismantled, loaded on a railcar, and hauled via the old rail route, across the bridge at the mouth of the Pecos, and on to the west canyon rim where it was reassembled and put to work again building towards the span that had been completed from the east side. Using a daily work crew that averaged 67 people, the bridge was completed in just 103 days at a cost of $250,108.00. The completed construction was 2,180 feet long, consisting of a combined cantilever and a 185-foot section of "suspended" lattice over the actual watercourse. The ironwork alone weighed 1,820 tons. With its completion, all that remained to bring the structure into service was the installation of the electrical signaling equipment on both approaches to it. Trains approaching from either way would be required to stop and inspect the bridge prior to crossing. On March 31, 1892, a special train carrying railroad dignitaries officially opened the Pecos Viaduct to regular rail traffic.

NPS photo The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, had repercussions that were felt as far away at the Pecos River Viaduct. Because of the bridge's strategic importance as part of the southern transcontinental railroad, the U.S. Army stationed troops at the Pecos River to protect security for the bridge and the increase in military rail traffic following the Japanese attack. During World I, the U.S. Army had stationed troops for a similar purpose, and, during the Mexican Revolution of 1917, Texas Rangers patrolled the bridge looking for saboteurs. Railways officials and the Office of Defense Transportation soon realized that the 48 year old bridge might be unable to carry all the weight it could be called on to bear, thus creating a bottleneck when the nation was rapidly mobilizing for war. Topographic studies by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1942 identified a suitable site for a new bridge located less than one-quarter mile south of the existing Pecos River viaduct. The War Production Board placed a high priority on building a new structure, thus enabling the railway company to obtain the needed steel at a time when it was in short supply. By the end of 1942, the Southern Pacific had successfully applied to the Office of Defense Transportation and received construction materials for the new bridge which was to consist of a number of continuous cantilever and plate girder spans perched on top of two huge concrete towers anchored in the river bottom. Work began on the piers in August 1943; and on December 21, 1944, the 1.2 million dollar bridge was completed and in service as the first regular freight train crossed the 1,390 foot long structure. Still in operation today, it is commonly known at the Pecos High Bridge.

Courtesy Lehigh Museum The 1890's Pecos Viaduct was kept as a standby for nearly five years following the completion of the new bridge. In 1949, the Southern Pacific contracted with the Robinson Erection Company (St. Louis, Missouri) to dismantle the historic bridge. Initially, the Southern Pacific had made plans for the purchase of the entire structure by the government of Guatemala for use in that country. Current literature on the subject provides conflicting stories on the fate of the old bridge. The Odessa News (October 15, 1978) states that the bridge was in fact sold to Guatemala, and, is still in operation in that country today. A post card of the 1892 bridge (Old West Collectors Series No. 46) states that "Because it was so well engineered the West Texas bridge was dismantled after 56 years [1948] and rebuilt across the Wabash River in Indiana." T.L. Baker writes that, initially, the Southern Pacific had made plans to sell the bridge to the government of Guatemala; however, the deal fell through resulting in the piecemeal sale of individual spans from the bridge to several different states and local governments for use as shorter bridges across streams within their political jurisdictions. Most of the other pieces and parts were sold to scrap metal dealers. |

Last updated: April 21, 2025