San Gabriel del Yunque-Ouinge and San Miguel

Española, New Mexico

Coordinates: 36.05731, -106.08356

#TravelSpanishMissions

Discover Our Shared Heritage

Spanish Colonial Missions of the Southwest Travel Itinerary

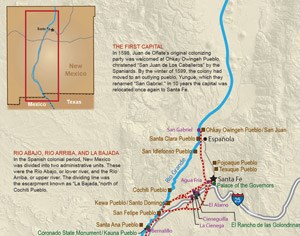

NPS map from El Camino Real de la Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail.

Photographer unknown, Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo

Archives (NMHM/DCA), 042236.

Photo by Peter D. Tillman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Jerry Friedman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Plan Your Visit

San Gabriel de Yunque-Ouinge, a National Historic Landmark, is located just west of San Juan Pueblo and the Rio Grande, on New Mexico State Road 74, 25 miles north of Santa Fe, NM. For more information about the San Gabriel replica, visit the Plaza de Española website.

Hispanic life in northern New Mexico is the subject of an online lesson plan, The Hispano Ranchos of Northern New Mexico: Continuity and Change. The lesson plan has been produced by the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places program, which offers a series of online classroom-ready lesson plans on registered historic places. To learn more, visit the Teaching with Historic Places home page San Gabriel de Yunque-Ouinge is featured in the National Park Service American Latino Heritage Travel Itinerary, and San Juan Pueblo is featured in the National Park Service American Southwest Travel Itinerary.

Last updated: April 15, 2016