Courtesy of San Antonio Missions NHP.

Ponce de Leon did not find the miraculous fountain, which, indeed, had never existed. Soto never knew the glory of being Florida's conquistador, but left a historical mark as the first European who navigated the lower Mississippi River. Dead from a fever, his body, wrapped and laid into a hollowed log made by his men, was submerged in the river. Neither did Coronado find the Seven Cities of Cibola nor the Kingdom of Quivira. He did not find the riches he had hoped for, but only hardworking Indians who lived by farming and resided in adobe houses of different levels. Since then, they are known as Pueblo Indians owing to the similarity of their homes to those in the villages of Spain. All had been a tale, influenced by the feverish imagination of Fray Marcos de Niza. This friar had echoed the vague notices that Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca brought to Mexico after his shipwreck of 1528 along the coast of Texas. The great wayfarer through North America lived among the natives for nearly seven years. Resolving to return to Mexico with three of his luckless friends, he finally undertook the trek through unknown lands until after many months, he met other Spaniards in the north of the present Mexican state of Sinaloa.

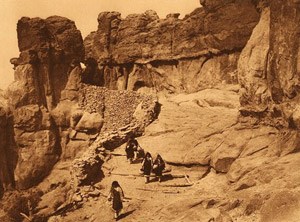

Photo by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952). Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Despite notable differences, the settlement of the Great North of Mexico, or New Spain, foreshadowed the conquest of the American West. For Hispanics, New Mexico, Arizona, and California were the "Spanish Far North." The "mission", as the Spanish crown understood it, was the self-imposed task to Christianize and civilize the native populations. Centuries later, the Anglo-American policy of expansion became the secular mission to extend civilization and democracy to the Pacific in obedience to the nation's mandate of Manifest Destiny.

"Wayfarer, there is no road, the road is made by walking," wrote the Spanish poet, Antonio Machado (1875-1939). Aside from indigenous trails, at the beginning of each region there were no formal roads;they had to be made by walking. It was the boots of the explorers and conquistadors, the sandals of the friars, the feet, perhaps bare, of Indian allies or servants, the hooves of horses and livestock, and the heavy, slow-moving solid wheels of the carretas, which cut into bedrock, crushed stone, and combed through the sand. Lone friars, or in the company of very diverse people, opened roads and established missions which today are monuments and commemorations of the past.

Photo by Larry Lamsa. Courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons.

The three fundamental institutions of Spanish policy in Hispanic North America were: the presidio or fort, as the outpost for defense and advance of the frontier;the mission for the indoctrination and integration of the natives;and the town council of the villages and cities as the seat of power for citizens. The symbiosis between these three institutions marked the Spanish experience. The singularity of North America (scattered native settlements, paucity of mineral wealth, including scarcity of water) gave the missionaries a special prominence. The missions were places of rest and refuge for travelers as well as schools for Christianizing and educating the Indian. Too, they were the targets of frequent native rebellions. The annals of the missions are spattered with the blood of missionaries. Often, Indians sheltered at the missions died along with the soldiers assigned to protect them. Many missions were the seeds of settlements that became villages or towns.

The work of the missionaries was pioneering and varied. The natives learned trades, came to know new technologies, and provided indispensable manual labor to construct the churches, which mark the paths of the missionaries. Grains, vegetables, and fruits from Spain were cultivated for the first time in the missions. Cattle, sheep, and rams were also raised. Irrigation ditches were constructed to carry water to the dry fields;water, more precious than gold or silver. The friars, with the labor of the natives, created new landscapes. Wheat complemented the native corn. Grapevines and wine are today hallmarks of California. Friars were loyal to the Christian principle of "ora et labora," pray and work.

Courtesy of the National Register.

There was so much to do for the natives (body and soul), that Kino, at once, was the builder of missions, rancher, stockman, and farmer. Junípero Serra, as the Father Superior, established the Franciscan mission system of California. Despite suffering from an ulcerated leg until his death, he, again and again, visited the newly established missions. He covered thousands of miles during this lifetime work in California that he can be known as the man who walked and walked....Also, Serra culturally changed the native people by introducing agriculture and irrigation. One of the Founding Fathers of California, Serra is the only Spaniard who has a statue in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.

Photo by Bigroger27509. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What do visitors hear and see from afar in their mission itinerary? They hear a church bell and make out a distant tower: sounds of the past and adobes that resist the passage of time. Towers and bells are historic symbols. The church, the wooden images, the painted murals, the orchard, the garden, and the cemetery of any mission, from Florida to California, are meeting places of two currents of western civilization: the Spanish and the Anglo-American. Preservation policies pertaining to monuments, the actions of the National Park Service, and the interest of the American public regarding its traditions, have made possible the preservation and conservation of old Spanish missions. Churches and missionary pathways are the best acknowledgements of a legacy whose architects were the friars and friendly Indians. Spain, the Hispania of yore, owes a special tribute to the generous official and private endeavors that allow the visitor to communicate with the past through beautiful trails and to reflect in the shade and silence of any mission.

Alfredo Jiménez

Profesor emérito de la Universidad de Sevilla

Translated by Joseph P. Sánchez, PhD

Angelica Sánchez-Clark, PhD

Barbara Mínguez Garcia

Last updated: April 15, 2016