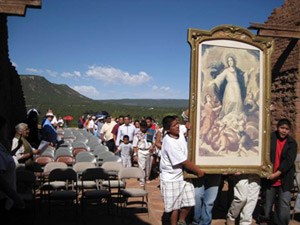

Photo by Larry D. Moore, 2010, CC BY-SA 3.0. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

No one will ever know why individual Indians, who came into Spanish missions, committed themselves to conversion, acculturation, and servitude. In some cases, the missions came to them, as they did to the Pueblos of New Mexico. Once in the mission neophytes, or new converts, would be expected to remain there until they were perfectly converted, that is, made into full members of the congregation. During the Spanish colonial mission period, perfect conversion was rare, as was the conversion of an entire tribe or pueblo to Christianity. Tradition has it that the missionaries never forced anyone into a mission, but once there, they could not leave. Those who ran away were often tracked down and returned to the mission. Those who did not succumb to the missionaries became enemies, who saw the friars as threats to their cultures, beliefs and spiritualism. Between conversion and rebellion, the missionaries' work was not for naught, for a kind of religious and cultural merging evolved that is evident today where missions once stood.

Who were the missionaries? What inspired them to renounce the world to live a life of piety and poverty and to surrender their lives for their God? They led lonely lives, in constant danger and fear for their lives. Along with their Indian charges, they, too, toiled in the missions, farmlands and ranches. They were responsible for those who lived with them and their welfare, often being the first to rise in the morning and, after bed check and prayers, the last to go to bed. To be sure, they were tough frontiersmen, who believed that the discipline they meted out to their neophytes was for their own good. They viewed Indian cultures, ways, and beliefs through the lens of Spanish colonial eyes and held European attitudes toward the natives.

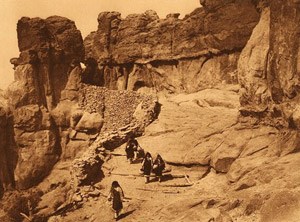

Photo by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952). Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The missionary paid allegiance to two masters: the Church and the State. While missionaries truly believed in doing God's work, they were also agents of the State whose job it was to pacify areas, particularly those that had mineral wealth or other valuable resources. With pacification, the land would be opened to settlers and investors. Settlers, such as farmers and ranchers, provided food supplies to miners engaged in extracting tin, iron, copper, salt, mercury, and other important resources to enrich the State and provide resources for trade, economic stability, and wars in Europe. The missions provided foodstuffs produced by neophytes for such ventures. Thus, religious conversion, acculturation, and vocational training served the needs of both Church and State pacifying a given area for economic, settlement, and military purposes;and Christianized citizens would emerge to serve both the Church and the State.

Regimentation marked the lives of mission Indians in several ways. They were expected to convert to Christianity and learn about their new religion through the catechism, or religious instruction. They were expected to learn Spanish and, through hymns, learn to sing or chant in Latin. They were expected to serve the friars as laborers, cooks, herders, gardeners, acolytes, sacristans, and porters. Friars waved the rule of obedience over the heads of neophytes. The escolta, mission guard, meted out whippings to punish disobedience. The Indians were expected to learn a new cultural norm: customs, traditions, behavior, and obedience to Church and State. A calendar of holy days, obedience to Spanish law and taboos of the new culture regarding bigamy, concubinage, and sorcery exposed the mission Indians to new ways. The Ten Commandments and the Laws of the Indies provided other lessons in strict obedience. Baptism was the first step in the neophytes' commitment to a new way of life. Finally, mission Indians were expected to learn a new vocation or trade that would make them loyal and productive citizens of the State.

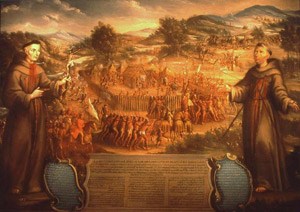

Attributed to Jose de Paez, 1765. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Frequent rebellions rocked the missions of northern New Spain throughout Texas, New Mexico, Pimería Alta (northern Sonora and southern Arizona) and California. Revolts ended with many deaths of missionaries and settlers and often with the capture and execution of rebel leaders. The oldest missions in New Mexico and present-day Chihuahua were the first to feel the pressures of rebellion. From 1599-1604, when tribes of the Sierra Madres spontaneously rebelled against colonial rule and missionary demands, to the planned revolts by the Tepehuans (1618), the Pueblo of New Mexico (1680) and the Tarahumara (1691), a string of rebellions spread throughout northern New Spain.

Park Photo by Heather Young.

The missions were not solely responsible. From 1598 in New Mexico, for example, colonial policies commonly in effect throughout the Spanish empire troubled the economically strapped Pueblo people. Although the friars protested them, the Spaniards imposed two dreaded feudalistic institutions on the Pueblos which would, in the long run, become focal points for rebellion. The first was the encomienda, which called for tribute to be collected from the Pueblos. The second institution was the repartimiento that required the head of household who could not pay the tribute to pay the value of the tribute in labor. In most cases following revolts, the missions were reestablished with a renewed respect for native values and without the encomienda and repartimiento.

by

Joseph P. Sánchez, PhD

Last updated: April 15, 2016