|

Explore more places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivisions, city planning, fairs, churches, and many, many park designs.

Origins of Campus Planning in AmericaScholars trace early campus planning in the United States to Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia. Thomas Jefferson's plan for the University of Virginia has been described as an "academical village," in which environment and landscape were closely tied to the purpose of the institution. These early ideas of campus planning would carry over into into the nineteenth century, when higher learning expanded dramatically in the United States. Over the past two centuries, campuses in the United States have come to represent a uniquely American landscape form which reflects American values and tastes. Times of ChangeFrederick Law Olmsted's first forays into landscape design in the mid-nineteenth century coincided with national trends of expansion and democratization. The 1860s saw the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the passage of the Homestead Act, both of which facilitated migration throughout the West. The passage of the Morrill Act in 1862 marked the beginning of the expansion of higher education in the United States, creating the land grant colleges—public universities established primarily to promote agricultural and scientific research. Around the same time, new women's colleges and schools for African Americans were also established. These new institutions signaled the increasing importance and accessibility of higher education for Americans.

Olmsted Archives Olmsted-Designed Campuses The College of California: Designing for Community Today known as the University of California, Berkeley, the College of California was one of Olmsted's first campus plans. Although the plan Olmsted proposed was not implemented by the college's founders, Olmsted's ideas about campus planning can be traced to his design for the college. After visiting the site in the foothills east of San Francisco Bay, Olmsted proposed a plan in which students lived in cottages, rather than dormitories. These cottages would be arranged in a "picturesque" style, with meandering roads and paths surrounding them. Areas of campus were to be separated by park-like areas. Olmsted departed from more traditional, symmetrical campus plans. He thought that such campuses were not conducive to growth and expansion. This decision showed Olmsted's vision for the future of the campus. As with his public parks, Olmsted designed with the future in mind. Olmsted envisioned a campus that would be integrated with the surrounding community. He felt that students would benefit from a balance between "a suitable degree of seclusion and a suitable degree of association" with the rest of the world. He particularly praised the area which would become Berkeley, California because it was both close to and separate from the growing city of San Francisco. Olmsted wrote, ". . . [students] should be free to use at frequent intervals those opportunities found in large towns and seldom elsewhere. Such is the argument against a completely rural situation for a college. On the other hand, the heated, noisy life of a large town is obviously not favorable to the formation of habits of methodical scholarship."

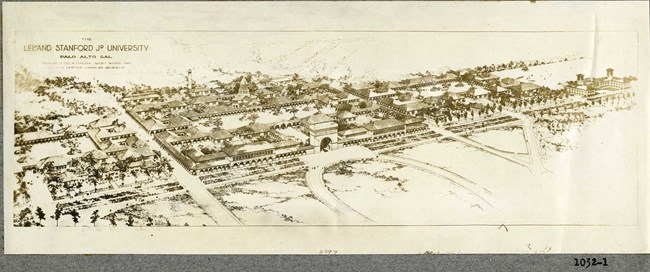

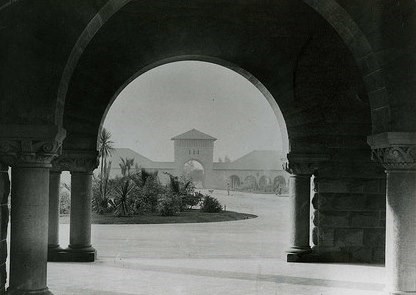

Olmsted Archives Stanford University: Designing for Sustainability For the campus of Stanford University, Olmsted proposed a campus uniquely suited to California's climate. The ambitions of the railroad financier and former California governor Leland Stanford dictated much of Olmsted's design work on the project. Stanford envisioned a campus monumental in scale and formal in design, while Olmsted proposed a campus nestled in the hills of Stanford's property. Stanford insisted the campus be built on flat land, with a grand axial approach to the center of campus.

Olmsted Archives As an opinionated and strong-willed client, Stanford's design ideas were largely implemented. However, Olmsted won a key disagreement over the campus landscape. Olmsted proposed that the main campus quadrangle, the largest of its kind at the time of its construction, be paved and contain circular planters of native plants, trees, and shrubs. Stanford ultimately agreed to this. Although the finished quad is strikingly more formal than most Olmsted designs, the quad design illustrates a key Olmsted principle—sustainability. Olmsted's recommendation of paved space and native plants over lawns showed an understanding of the resources needed to maintain a landscape. The 8,000 acre project ultimately cost the Stanfords $30 million.

Olmsted Archives University of Mississippi: Designing for Growth Like Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the Olmsted Brothers approached design and planning with the future in mind. The Olmsted Brothers foresaw the growth of the University of Mississippi, choosing to orient the campus around an east-west axis. Roads around the edges of the campus served to establish a cohesive, central campus core. Building off of the university's earlier plans, the Olmsteds' plans and studies produced a campus consisting of a series of quads connected by axes and cross-axes. The firm's work at the University of Mississippi spanned nearly 40 years and resulted in over 1800 plans, making it the single largest body of plans in the Olmsted Archives.

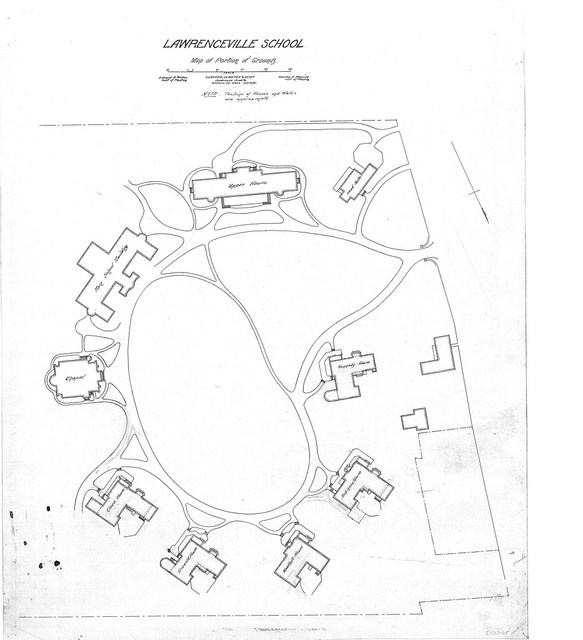

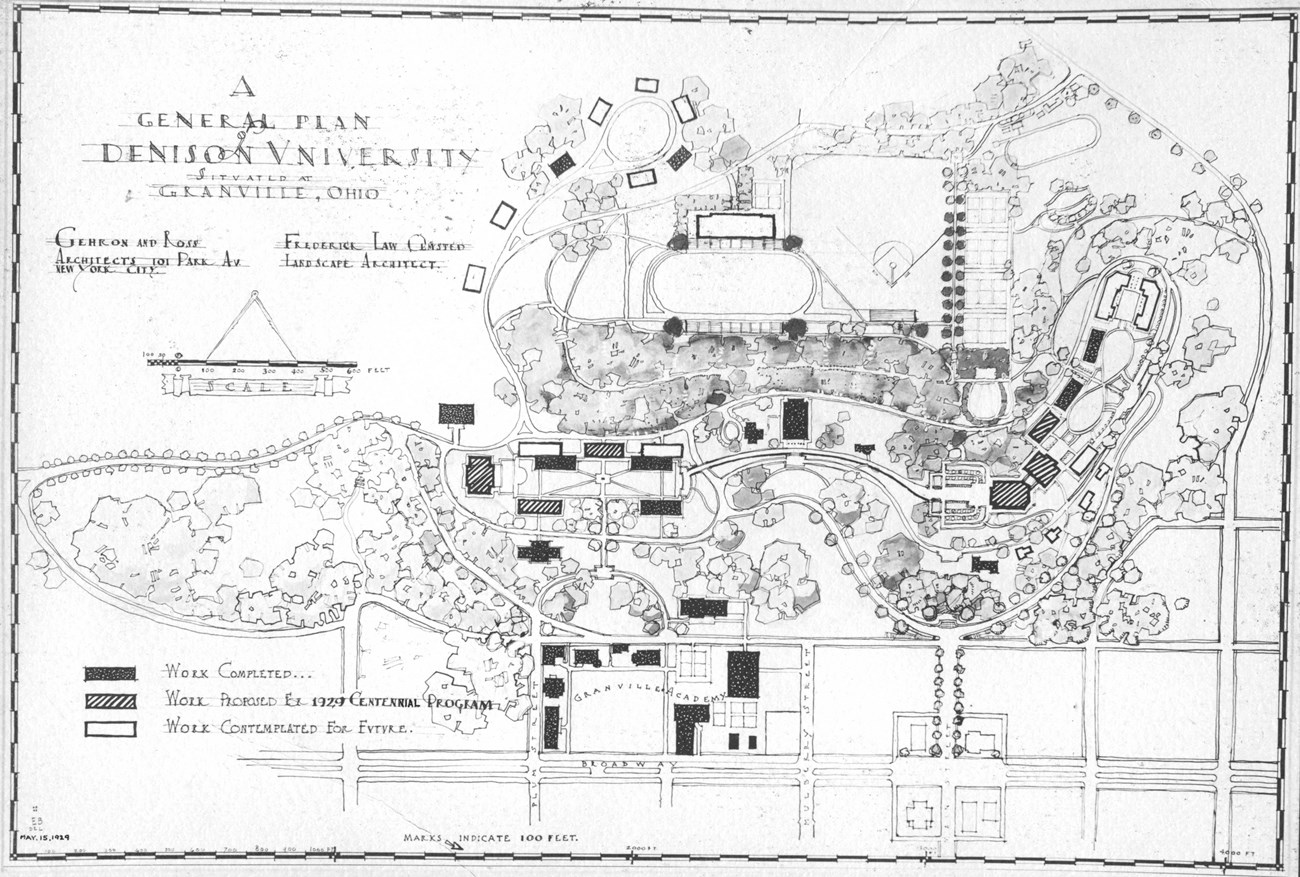

Olmsted Archives Other Olmsted Campus Projects

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives

Olmsted Archives Further Reading Coulson, Jonathan, Paul Roberts, and Isabelle Taylor. University Planning and Architecture: The Search for Perfection. New York: Routledge, 2015. Duke University Office of the University Architect. "The Legacy of Landscape Architecture at Duke."http://architect.duke.edu/landscape/History%20of%20Landscape%20Architecture%20at%20Duke1.html. "Historic Contexts." In Campus Heritage Plan. University of Cincinnati, 2008. Kowsky, Francis R. "College and School Campuses." In The Master List of Design Projects of the Olmsted Firm, edited by Lucy Lawliss, Caroline Loughlin, and Lauren Meier. Washington: National Association of Olmsted Parks, 2008. Olmsted, Frederick Law. "Berkeley: A University Community." In Civilizing American Cities, edited by S.B. Sutton, 264-291. New York: Da Capo Press, 1997. Rybczynski, Witold. "Olmsted Meets the Governor." In A Clearing in the Distance, 367-372. New York: Scribner, 1999. Turner, Paul Venable. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984. |

Last updated: March 4, 2024