|

Frederick Law Olmsted and the Olmsted Brothers played a significant role in planning and designing some of the nation’s most influential exhibitions and fairs. In 1890, when Chicago won the honor of hosting the World’s Columbian Exposition, Frederick Law Olmsted was asked to help select the site for the fair. While groups throughout the city lobbied for their own neighborhoods, Olmsted envisioned a site that would provide dramatic views of Lake Michigan as the backdrop for the fairgrounds. Two decades earlier, Olmsted and Vaux had laid out the 1055-acre South Park, which included Eastern and Western Divisions and a wide swath to connect them, the Midway Plaisance. The Western Division, renamed Washington Park, was largely implemented by the time the fair was being planned. In contrast, the Eastern Division, which had become Jackson Park, had only a small area of finished landscape. Because of Jackson Park’s lakefront setting and its incomplete state, Olmsted advocated for it as the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Olmsted and Henry Codman articulated a guiding theme similar to that of the original South Park Plan- a series of navigable waters that would be linked to Lake Michigan. In a meeting with consulting architects Daniel H. Burnham and John Welborn Root, the planners sketched the scheme at a large scale on brown paper bag. The plan featured a great architectural court with a formal canal leading to a series of lagoons. In the middle of the lagoon system, Olmsted suggested carving a natural sandy peninsula into a large secluded wooded island meant to remain free of buildings or structures. Although he had pressure to build various exhibits on the island, Olmsted argued to protect its sylvan character, and only the Japanese pavilion and garden that coincided with the Horticultural Building were allowed. The island would stand in stark contrast to the magnificent campus of white neoclassical buildings that would be accessed by boat and train. After the death of John Welborn Root in 1891, Burnham continued as Director of Works for the World’s Columbian Exposition, and Olmsted’s role as consulting landscape architect remained pivotal. When the fair opened on May 1, 1893, visitors were dazzled by the gleaming “White City.” Six months later, after the fair closed, many of its plaster buildings were destroyed by fire, and almost all of the rest were razed. The South Park Commissioners retained Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot to transform the site back to parkland. The firm’s 1895 plan featured the lake, lagoons and playfields in a manner similar to that of Olmsted and Vaux’s original plan. The later plan did, however, retain the Fine Arts Palace as the Field Columbian Museum (now Museum of Science and Industry) as a vestige of the fair. After Frederick Law Olmsted’s death, the Olmsted Brothers continued the legacy by designing a number of other fairs and expositions. The Olmsted Brothers developed numerous plans for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego’s Balboa Park. These plans were not fully realized, however, because local authorities insisted on altering the location of the fair, and the Olmsted Brothers withdrew from the project. The firm had better success in planning other fairs, including the 1905 Lewis & Clark Exposition in Portland, Oregon, and the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle (also listed in Parks, Parkways, Recreation Areas and Scenic Reservations), now the Rainier Vista in the heart of the University of Washington campus. The firm also designed exhibition sites within important American fairs, such the National Cash Register Exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, churches, and the many, many park designs.

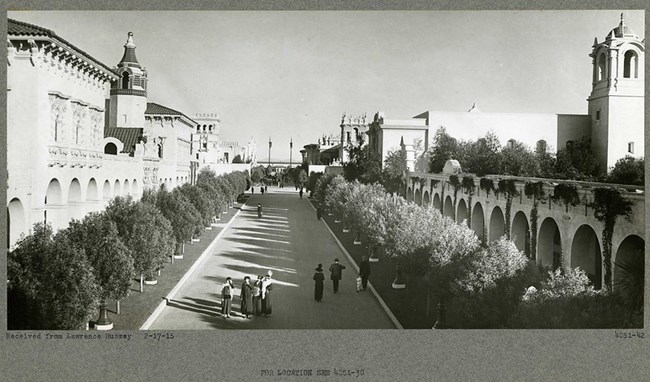

Olmsted Archives Balboa Park (San Diego, CA)Much like their father before them in Chicago, John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. were hired in 1910 by the San Diego Building and Grounds Committee to design the landscaping plan for an exposition that would, hopefully, draw millions to the city: The Panama-California Exposition. Though John Charles would take the lead on this project, both brothers studied Spanish Mission style architecture, prevalent in Southern California. Spanish Mission style has strong Native American and South American influences, with stone exteriors and red tile roofs. For the grounds of the Exposition, the Building and Grounds Committee constantly changed their wants and expectations, forcing Olmsted Brothers to restructure their designs. The final straws that broke the brothers’ back was the recommendation that, not only should the entire location of the site be changed, but that a railroad should cut directly through it. Olmsted Brothers were unwaveringly opposed to both changes, especially the addition of a railroad, because this would eliminate all possibilities of creating a semi-rural respite from a city. The brothers had learned well from their father, as Olmsted Sr. believed that was the main function of a large urban park. On September 2nd, 1911, a telegram arrived in San Diego from Olmsted Brothers in Brookline, stating that “our professional responsibility as park designers will not permit us to assist in ruining Balboa Park.” Ouch. It appears San Diego’s leaders were so focused on the Exposition and the potential real estate development that would follow, that they couldn’t envision a time when people would desperately need open space. Despite Olmsted Brothers’ self-removal from the Exposition and Balboa Park, years after the project’s completion, people still flock to Balboa Park seeking the same things Olmsted Brothers wanted to prioritize: open green space, fresh air, respite in nature, relaxation.

Olmsted Archives World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago, IL)When Chicago was chosen as the city to host the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Frederick Law Olmsted was called on to adapt his initial designs for the South Park Commission site, now called Jackson Park, Washington Park, and the Midway Plaisance, to be more appropriate for a fairground.Olmsted would collaborate with architect Daniel Burnham to create Venetian-inspired please grounds complete with waterways and natural areas for quiet reflection, complementing the grand architecture of the fair. This collaboration between the two men would help launch the “City Beautiful” movement, promoting the inclusion of green space in urban centers to improve the community’s morale and quality of life. Twenty years before the exposition, Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had conceived of lushly planted lagoons for this area of Chicago, which would finally come to fruition. Olmsted would dredge the swamp in the area, leaving an island at the center of the lagoon, dubbed The Wooded Island, which was meant to be the central piece of landscape architecture at the fair. As Olmsted would explain it, his goal in the design at the Chicago World’s Fair was ““to establish a considerable extent of broad and apparently natural scenery, in contemplation of which a degree of quieting influence will be had, counteractive to the effect of artificial grandeur and the crowds, pomp, splendor and bustle of the rest of the Exposition.”

Olmsted Archives Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (Seattle, WA)To celebrate and publicize the development of the Pacific Northwest, it was decided a world’s fair would be held in Seattle. In October 1906, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Company hired John Charles Olmsted to design the grounds, believing he would create a breathtaking design like his father had at the World’s Columbian Exposition.John Charles faced two major constraints in his work for the exposition. The first was that the budget, which would cover the clearing of 200 acres, grading slopes, and planting grounds was only $350,000, which was a tough deal considering his father Olmsted had gotten over triple that amount to design his world’s fair sixteen years earlier. The second constraint was that once the fair was finished, the buildings and grounds would be given to the University of Washington. John Charles developed a plan that would serve both the needs of the fair and of the university. As opposed to other world’s fairs of the time, the design of the A-Y-P relied on the natural scenery, including nearby Mount Rainier, Lake Washington, and Lake Union, as focal points to lay out buildings, roads, and paths around. Incorporating the surrounding landscape, adapting to the topography of a site, using native vegetation and water features are all characteristic of Olmsted designs. John Charles' design of the A-Y-P would be dubbed the “Rainier Vista” and is the central core of the University of Washington campus, still cherished today. |

Last updated: June 18, 2024