|

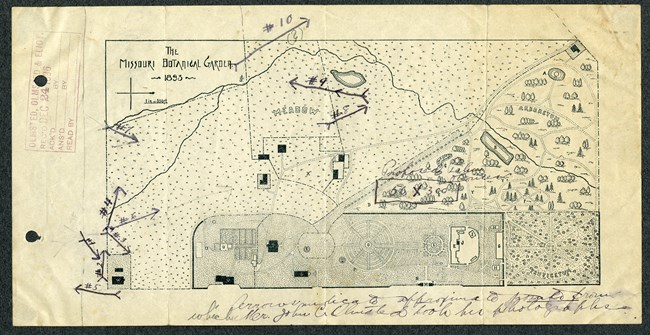

Arboreta and gardens constitute a relatively minor category for the Olmsted firm with about twenty projects, about fifteen of which produced design plans. It represents, however, a project type associated with a handful of major arboreta completed in association with park systems in Boston, Louisville and Seattle, as well as important arboreta/botanic gardens in cities such as Brooklyn, New York. The earliest of these projects and the one most closely associated with Frederick Law Olmsted is the Arnold Arboretum (1879-1897). It is located in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston between Franklin Park and Jamaica Pond along the Arborway and forms a significant piece of the Emerald Necklace park system. Created as one of the first successful American arboreta open to the public, the Arnold Arboretum serves as a prototype, with dual functions as a scientific study collection of hardy trees and as a scenic pleasure ground that provides shelter and respite from the city. While the Arboretum’s first director, Charles Sprague Sargent, sought to create a museum for the display of living specimens, Olmsted brought his park experience, noting his design intent: We want a ground to which people may easily go after their day’s work is done, and where they may stroll for an hour, seeing, hearing, and feeling nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets, where they shall, in effect, find the city put far away from them… What we want most is a simple, broad, open space of clean greensward, with sufficient play of surface and a sufficient number of trees about it to supply a variety of light and shade… We want depth of wood enough about it not only for comfort in hot weather, but to completely shut out the city from our landscapes. After several years of negotiations between Harvard University and the City of Boston and a long series of design studies, Olmsted and Sargent created a plan for the Arnold Arboretum in which trees were grouped by family and genus following their phylogenetic order, with a curvilinear road system that negotiated the site’s undulating topography so that visitors would experience the tree collection in a strictly logical order. This dual function of scientific museum and aesthetic pleasure ground is still intact more than a century after the Arnold Arboretum’s creation. The firm was consulted as early as 1893 on the future of the Missouri Botanical Garden, which was in a period of transition following the death of its founder, Henry Shaw, in 1889. Shaw had been instrumental in founding both the botanic garden and later a School of Botany at Washington University in St. Louis and was involved in negotiations regarding the role the university would play in the care and upkeep of the botanic garden. Unlike the Arnold Arboretum, the Missouri Botanical Garden was established as a not-for-profit institution rather than a direct affiliate or extension of the university. The Board of Trustees asked the Olmsted firm to submit a plan to both evaluate the current condition of Shaw’s garden and make plans for its future. Although the Olmsted master plan was adopted by the Trustees, only a portion was implemented. Listed in the Master List in both the parks and arboreta categories, the Missouri Botanical Garden is, like the Arnold Arboretum, a scientific botanical garden that is open to the public and serves as a pleasure ground. Much of the Olmsted firm’s arboreta/botanic garden work occurred in the mid-1930s, with several projects completed concurrently with work by the WPA. The Olmsted firm created plans for the Seattle Arboretum (1884, 1903-1906, 1934-1939), Morris Arboretum in Philadelphia (1909-1933), listed as Chestnut Hill, Bernheim Arboretum in Louisville, Kentucky (1929-1957) and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden (1907-1919). Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and James Frederick Dawson are largely credited with the implementation of the plans for the Seattle Arboretum at Washington Park, which opened in 1934, and with the Olmsted firm’s plans for the Bernheim Arboretum, implemented the following year. While the Master List indicates sixteen plans prepared for the Hartford Arboretum between 1934 and 1936, it is difficult to ascertain the full extent of the firm’s design work there. In addition to the large public arboreta, between 1933 and 1935 the Olmsted Brothers completed more than fifty design plans for the interior courtyard, fountain and front planting at the Frick Museum (Collection) in New York City. The Master List includes other lesser-known botanic gardens that progressed into design in Birmingham and Kellyton, Alabama, and Sebring, Florida. Text taken from The Master List, written by Lauren Meier Explore other places like country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

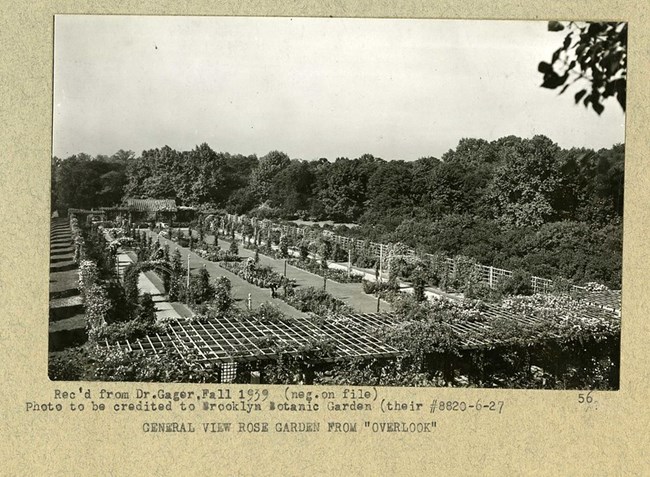

Olmsted Archives Brooklyn Botanic Garden (New York City, NY)After Frederick Law Olmsted’s revolutionary work on Prospect Park, the City of Brooklyn purchased an additional 52-acres of land, for additional park space but with the hope that it could be turned into a garden. The land was left undeveloped until 1910, at which point Olmsted Brothers were called in to create the sites first plan. John Charles and Frederick Jr. worked closely with C. Stuart Gager, Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s first director. Gager, stationed in Missouri before making the trip to Brooklyn, was in constant communication not only with Olmsted Brothers, but also McKim, Mead, and White, who were commissioned to design the gardens laboratory and plant houses. Though Brooklyn Botanic Garden is largely the product of Harold Caparn, the landscape architect chosen to when construction on the Garden was commenced, Olmsted Brothers original design still seeps through in every corner. A walk through Brooklyn Botanic Garden will transport you back in time, with a chance to learn from the some of the country’s leading landscape architects

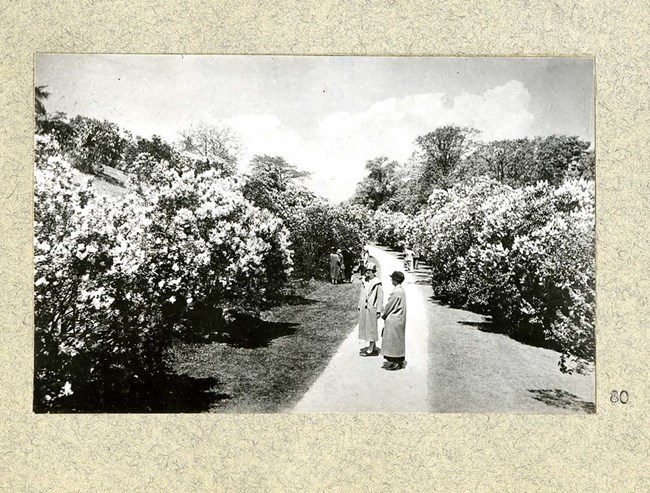

Olmsted Archives Arnold Arboretum (Boston, MA)In 2019, Meadow Road was transformed to the 1860s, becoming a Parisian carriage road that led Amy and Aunt March right into the oncoming path of Laurie. That carriage road was the same one Charles Sprauge Sargent, hired as the founding director of the Arboretum, asked Olmsted to design with him, revealing the planting arrangements they had worked so hard on. Though it would go on to become North America’s first public arboretum, Olmsted did initially have some reservations about the project. “A park and an arboretum seem to me to be so far unlike in purpose that I do not feel sure that I could combine them satisfactorily” – Frederick Law Olmsted July 8th, 1874 in a letter to Sargent In 1868, the same year Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women was published, James Arnold, a whaling merchant from New Bedford, dies and gives Harvard $100,000 to create an arboretum on land owned by farmer Benjamin Bussey. The natural woods of Bussey farm were incorporated into the plan, and to this day, there is still substantial growth in those woods. Like many Olmsted designs, the intention was naturalistic, fitting in with existing topography and vegetation. However, to create a living museum some alteration was in order. While walking along the main road of Arnold Arboretum, you’re presented with plant collections sequentially according to genus. If you’re a fan of Frederick Law Olmsted, you may have discovered that many of his great projects have been significantly altered over time, some completely disregarding Olmsted’s original designs when doing renovations. Arnold Arboretum wasn’t just another of Olmsted’s great public parks; it also served as a tree museum and scientific research station. In the 148 years since Arnold Arboretum was established, the dual purpose of park and museum has prevailed.

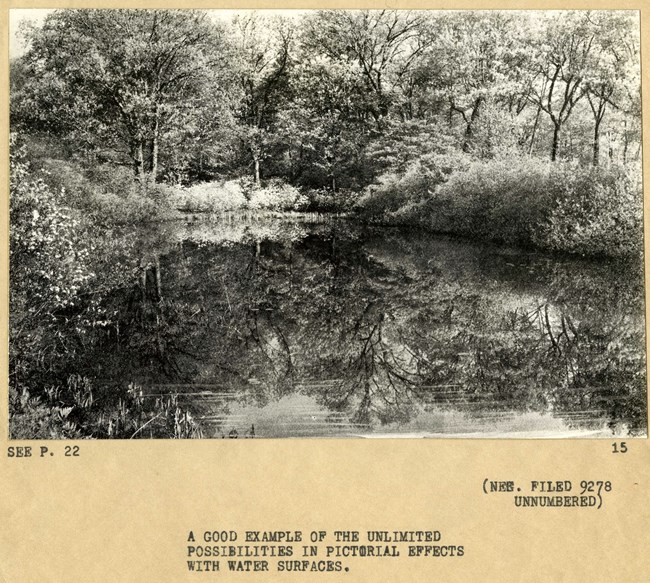

Olmsted Archives I.W. Bernheim Arboretum & Herbarium (Louisville, KY)The story of the I.W. Bernheim Arboretum and Herbarium is a rags to riches story. In 1867, eighteen-year-old Isaac W. Bernheim immigrated to the United States from Germany with only $4 in his pocket. After several years struggling to make a living as a peddler, jumping from New York, to Pennsylvania and New Jersey, finally moving to Kentucky to go into the distilling business.Over the years he achieved great wealth and success through his Bernheim Brothers Distilling Company and their famous bourbon. His love of sculptures and the community in which he made his fortune manifested in several gifts: a statue of Abraham Lincoln for the Louisville Free Public Library and Thomas Jefferson in front of the Jefferson County Courthouse. In 1929, Bernheim bought and endowed the land that would become the I.W. Bernheim Arboretum and Herbarium, which now stretches over 16,000 acres, as a gift to the people of his new homeland. Bernheim’s goal was to provide a place where the bond between people and nature could be renewed and restored. His vision included an arboretum and natural forested areas infused with the arts, providing a unique site to experience nature. Olmsted Brothers would begin work on a site plan for the Arboretum and Herbarium in 1931, and their original landscape design was adopted in 1935. Work continued until 1950, as the land was prepared to Bernheim’s intentions. Following the Olmsted Brothers plan, three small lakes and a road traversing the land were built before any of the collection was planted.

Olmsted Archives Frick Museum (New York City, NY)When industrialist Henry Clay Frick died in 1919, it was decided by the trustees of his estate that the mansion home had built five years earlier would be transformed into a museum. It would take several years for the museum to be fully realized.In 1935, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was commissioned by the trustees of the Frick estate to design an elevated garden on fifth avenue, to be known as the Fifth Avenue Garden. Olmsted Jr.’s design included an open lawn, neoclassical urns, and several magnolias set against the mansions limestone façade. Olmsted Jr. served as the garden designer, converting this Gilded Age residence into a museum and art history library open to the public. Located right next to Central Park, Jr. took inspiration from his father and shaped the garden using fresh plantings that aligned with the work of the museum’s architect.

Olmsted Archives Seattle Arboretum (Seattle, WA)In 1903, Seattle engaged Olmsted Brothers, with John Charles Olmsted taking the lead, to study the city’s open space, and make recommendations on its potential. Prior to Olmsted's involvement, the idea of an arboretum was already in the works, in conjunction with the new University of Washington, where Olmsted would later consult.Seattle legislation had made a trip to the Arnold Arboretum in 1891 and was taking inspiration from the Senior Olmsted’s work. However, it would be another 33 years, in 1936, that the Seattle Garden Club hired Olmsted Brothers to provide the arboretum’s first planting plan. John Charles Olmsted recommended a roadway to border the Arboretum and expanding the property's boundaries to prevent residential encroachment. James Dawson of Olmsted Brothers created the master plan for the plant collections. Dawson had grown up on the grounds of the Arnold Arboretum, with his father being the first plantsman there, and was prepared to give Seattle an original design. Formally called the Seattle Arboretum, this project would become one of Olmsted Brothers last in Seattle. Olmsted Brothers' plan for Washington Park Arboretum made sure certain areas would be preserved for wild growth, while some were cleared for interior views.

Olmsted Archives Missouri Botanic Gardens (St. Louis, MO)In 1896, Olmsted Brothers became the first landscape architects hired to work on the Missouri Botanical Garden, calling for a comprehensive arrangement of plant material and the removal of the Linnaean House, then being used as an orangery. Little of John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s plan was implemented- the Linnaean House is still used as a public greenhouse.Olmsted Brothers' most intact design element of the Missouri Botanical Garden was an 1899 recommendation for a 220-acre addition, known as the North American Tract, executed in 1905. Another Olmsted Brother addition, carried out in 1909, included a complex serving as an herbarium, library, and administrative building. |

Last updated: June 13, 2024