|

“No great town can long exist without great suburbs,” wrote Frederick Law Olmsted in 1868. At the time Olmsted and his then partner Calvert Vaux were designing Riverside, a 1600-acre suburb of Chicago. The suburban and town planning work of Olmsted and his sons clearly demonstrates the full range of social, economic, and environmental concerns that their designs addressed. More than 475 proposals for or inquiries about subdivisions and suburban communities had a job number assigned to them by the Olmsted firm. These projects varied greatly in the degree of the firm’s involvement, with many showing no activity beyond initial correspondence. It is estimated that one or more plans were prepared for only 370 of these projects. The undertakings in this category also varied greatly in scale, from the modest estate of a single landowner seeking to subdivide his holdings, to a twenty-five square mile area on the Palos Verdes peninsula near Los Angeles. While much of the subdivisions work took place in the northeast, the firm was active across the country and in Canada, particularly in cities in which it would have been familiar to clients through its work on urban parks and regional or state park systems. The 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century were a time of growing activity in this field for the firm. By the 1920s, when suburban America was growing at twice the rate of its central cities, the design of residential communities represented a significant portion of the firm’s overall business. After World War II, the number of such projects dwindled. Frederick Law Olmsted’s suburban work reflected his romantical nineteenth century view that a suburb, if well planned, would combine the charm of the country with the convenience of the city. It would provide “the most soundly wholesome forms of domestic life,” and demonstrate “the best application of the arts of civilization to which mankind has yet attained.” The planning work of his sons reflected an early twentieth century confidence that technology and the expertise of planners, administrators and design professionals could be harnessed to shape well-ordered, functional communities. Suburbs, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. held, required the kind of professional planning heretofore only seen in urban design and large-scale landscapes like Central Park. It was crucial to apply the emerging science of city planning to these urban additions. As with their park plans and other landscape designs, there is no formulaic “Olmsted style” that can be associated with residential communities: each plan is sensitive to its locale and topography. The articulation of boundaries; differentiation of street width according to type of traffic; provision of common spaces and other amenities that enhance the character of a place and encourage social interaction; and use of deed restrictions to enforce maintenance and preserve architectural and other community standards that are hallmarks of the firm’s suburban work that continue to influence suburban design today. The Olmsteds believed the residential suburb was deserving of the best efforts of planning and design professionals. In this complex cooperative enterprise, it is the comprehensive master plan, as Olmsted Jr. stated, that is key to creating “harmonious, beautiful and convenient residential communities.” Text taken from The Master List, written by Susan L. Klaus Explore other places like gardens, churches, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, city planning, campuses, fairs, and the many, many park designs.

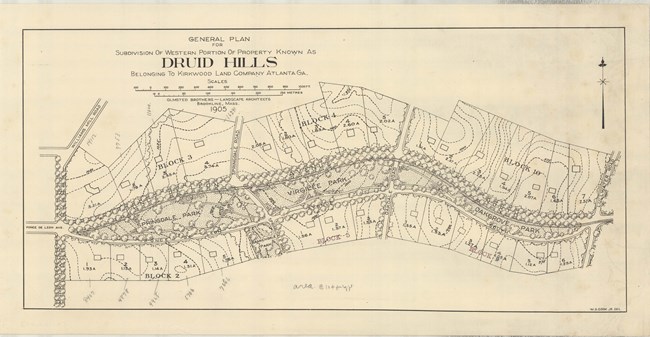

Olmsted Archives Druid Hills (Atlanta, GA)Atlanta entrepreneur Joel Hurt, who had already developed transportation, utilities, and real estate in the city acquired a large plot of land for residential use. To gain public support for his proposal, Hurt reached out to Atlanta’s most prominent families, including Coca-Cola founder Asa Candler. Frederick Law Olmsted first came to Atlanta in the late 1880s, on the invitation of Hurt, where Olmsted listened to his comments on the physical developments of the growing city. In his earliest proposal for Druid Hills, Olmsted stated the land had “roads of moderate grace and curves, avoiding any great disturbance of the natural topography.” Olmsted agreed to take on Druid Hills and began developing a plan to unify the community by unifying the landscape, transportation, and people. After several visits to Atlanta, financial setbacks halted the project for several years. Before work resumed, Frederick Law Olmsted had retired, and the work was passed on to Olmsted Brothers. Though development on the 1,300-acre plot of land began after Olmsted’s retirement, his designs are still a prominent part of the community. Olmsted designed a stretch of land following Druid Hills central roadway, Ponce De Leon Avenue, where 6 narrow public spaces were incorporated to separate vehicular traffic from pleasure traffic. Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons created a magnificent urban neighborhood that became Atlanta’s first suburb. The powerful combination of structure and natural elements created a relaxing effect on the tensions of urban life. Druid Hills was completed in 1905 and represents a major innovation in suburban design, one that influenced suburbs all over Atlanta.

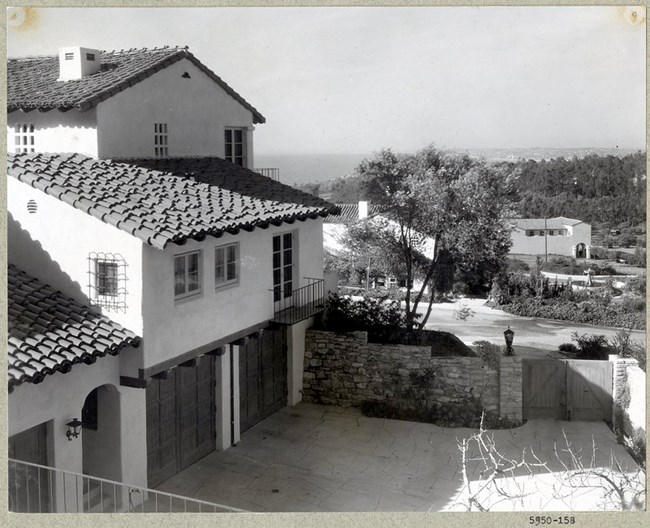

Olmsted Archives Palos Verdes (Palos Verdes, CA)In 1913, a group of California investors purchased 25,000 acres of land on the Palos Verdes Peninsula and hired Olmsted Brothers to develop the expansive coastal landscape. Originally both John Charles and Frederick Jr were working on the project, however World War One caused years of delays, and by the time work resumed in 1920, John Charles had died, and the development of Palos Verdes was left to Frederick Jr. Jr. was assigned the task of replicating a Mediterranean oasis in Palos Verdes, and it would become one of Olmsted Brothers largest and most complex projects. Taking input from scientists, engineers and horticulturists, Jr. transformed Palos Verdes from a rugged, hilly terrain to 16,000 acres of homes, country clubs, resorts, golf courses, and parks. In a 1923 report explaining his decisions on the entrance to Palos Verdes, Jr. would " advise against a large plaza or any other marked demonstration at the property line where it would be liable to be spoiled by developments in contact with it outside the property. I think the most effective treatment at the entrance will be… passing through this sylvan gateway for a considerable distance then widen out into an impressive demonstration where the view of the valley and hills and sea can burst upon one.” Even though the entirety of Olmsted Brothers’ plan was never realized, the concept they brought to Palos Verdes of a controlled, exclusive, Mediterranean-style community lives on, and has influenced the development of surrounding communities. The sweeping views and vistas of the rocky coast and Pacific Ocean Jr. provided for so many residents of Palos Verdes was just too enticing for him, and in 1925, Jr. would move his family to a home in Palos Verdes, where he could continue to work.

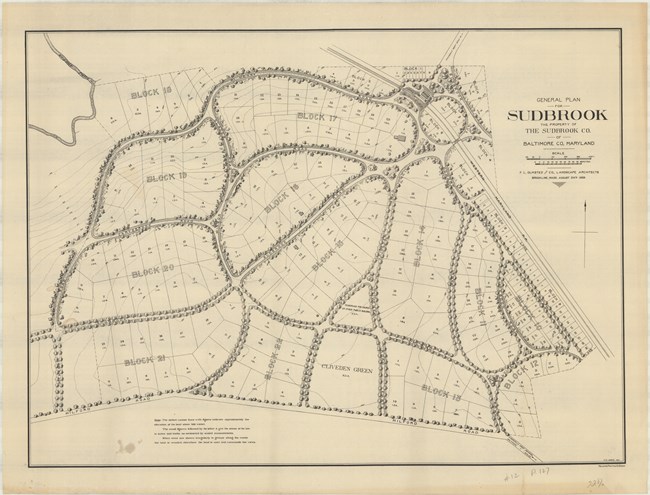

Olmsted Archives Sudbrook (Baltimore, MD)John Howard McHenry would first contact Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. in 1879, asking him to design a suburban community on his 850-acre estate, Sudbrook, located eight miles outside of Baltimore. After McHenry’s death in 1888, a group of Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore investors formed the Sudbrook Company, purchasing 204 acres of McHenry’s estate to fulfill his goal of a suburban community.Olmsted Sr. would work with John Charles on Sudbrook, submitting their plan August 1889. The smallest of the three residential communities designed by Olmsted Sr., Sudbrook artfully manifests Olmsted’s design principles for a suburban community, with his most prominent design feature being the curvilinear road pattern he implemented. Olmsted Sr. believed the curved roads would discourage through traffic and “enhance the domestic atmosphere of the village by creating an enclosed, intimate space”. The Olmsted design also included triangles of open green spaces at intersections, intended for gatherings of residents, which it is still used for. The approach road to Sudbrook took the community through a distinct entranceway: a narrow bridge, after which five roads fanned out into the community. Additionally, hardwood trees and lush vegetation lined the roads of Sudbrook. At Sudbrook Olmsted included sixteen deed restrictions, the most he had ever done, to protect the visual quality of his plan, and preserve the residential character of the neighborhood. The restrictions included single family homes being placed on lots of at least one acre, set back 40 feet or more from the street, and 10 feet or more from the neighboring property, an early form of zoning regulations.

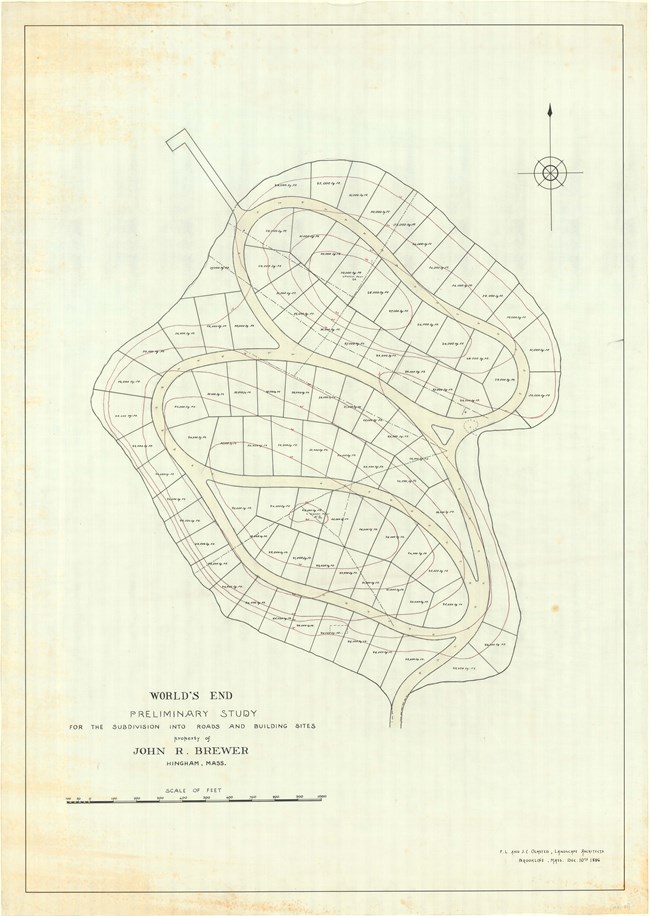

Olmsted Archives World's End (Hingham, MA)In 1856, Boston businessman John Brewer built himself a mansion in Hingham, MA. Over the next thirty years, Brewer acquired most of the peninsula, as well as two neighboring islands. Brewer turned his land into a vast and varied farming estate. He produced crops and raised animals.Years later in 1889, Brewer would reach out to Frederick Law Olmsted, asking him to design a residential subdivision on his peninsula that would be called World’s End. Olmsted’s plan for World’s End included 163 plots for homes, all connected by tree-lined roadways. While cart paths were cut and trees planted, the development never occurred. While the planned community was never built, Olmsted’s plan was partially realized in the creation of tree-lined carriage roads that are currently used as walking paths. Olmsted’s plan was truly realized in the plantings at World’s End, with hedgerows boarding Brewer’s old farming fields.

Olmsted Archives Boca Grande Land Company (Boca Grande, FL)In 1911, the Boca Grande Land Company hired Carl Rust Parker to help develop plans for the new town and a hotel to match, now the historic Gasparilla Inn. Parker had previously worked for Olmsted Brothers, however between 1910 and 1919, he was working independently.Despite leaving the Olmsted Firm, Parker’s work followed the Olmsted philosophy that all designed spaces should have a coherent character. In the years after Parker’s involvement, little was done to maintain the landscape, and the appearance of the whole area had begun to deteriorate. In late 1924, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. visited the Boca Grande Land Company, writing a nine-page report of the scenery. Olmsted Jr. would visit again in 1925, working to preserve the village Parker had designed, and retouch the beachfront areas. Olmsted Brothers worked to reinvigorate the area, dealing with the smallest of details like what color to paint the new school, and where bird baths should be placed. The design included moving a boat house to preserve a line of mangroves. The biggest challenge at Boca Grande was the relocation of the railroad, with Olmsted Jr. writing extensively on where the proposed county road should go. Today’s county road and railroad follow Olmsted Jr.’s plan, lined with the native plants he had envisioned.

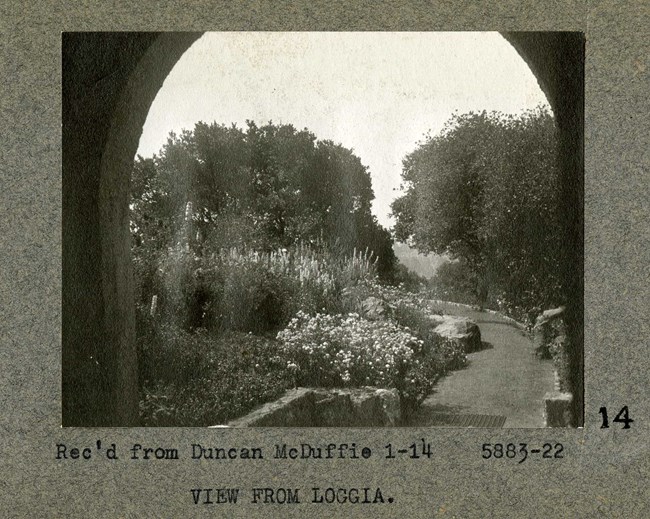

Olmsted Archives St. Francis Woods (San Francisco, CA)In 1912, the Mason-McDuffie Company purchased 175-acres of land with the hopes of creating one of the finest residential parks in the nation. Duncan McDuffie, who was responsible for numerous developments around the Bay Area, hired Olmsted Brothers to design the landscape of the community one year later.The Mason-McDuffie Company had already employed Olmsted Brothers for several earlier developments. They were tasked with designing a curvilinear street plan, striking a perfect balance with the preservation of large open areas of nearby parkland. Led by firm member James Dawson, Olmsted Brothers laid out the streets to conform to the site’s natural topography. In accordance with McDuffie’s request, all electrical and telephone wires were placed underground. St. Francis Wood was designed to be a residential community, with wide streets and sweeping vistas of the nearby Pacific Ocean. As with many Olmsted projects, communication with the site’s architect was crucial. Today, much of the neighborhood remains as it was intended in Olmsted’s original design.

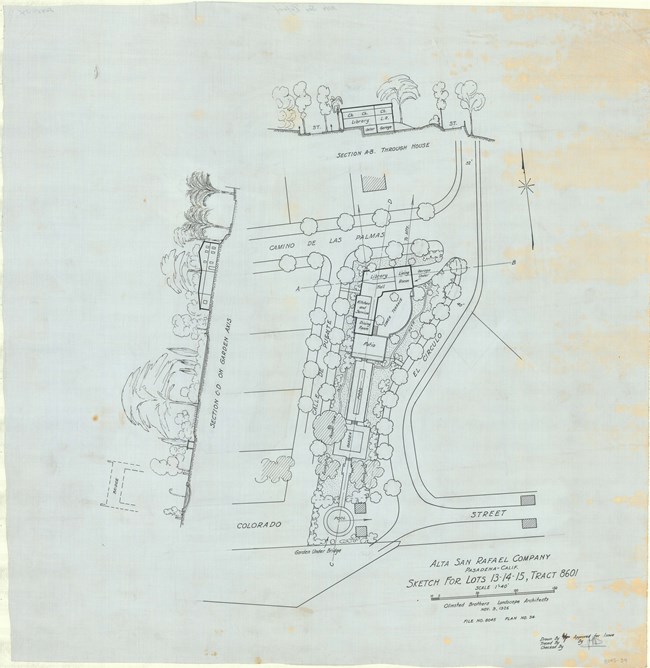

Olmsted Archives Alta San Rafael (Pasadena, CA)Alta San Rafael is a thirty-acre single-family residential subdivision of 35 lots designed from 1925 to 1930 by Olmsted Brothers. The site’s plan is intended to maximize local topography to capture scenic views and create enclosures from steep terraces and sharply curved streets.Alta San Rafael is an early example of a residential development with design restrictions intended to conserve the neighborhood’s overall architectural character as well as its environmental quality. Homes around Alta San Rafael were Mediterranean Revival homes designed by some of the most prominent architects of the day. In their design, Olmsted Brothers included thickly planted street trees and consistently used Arroyo stone to provide site-specific uniformity. While regulated developments like Alta San Rafael were experimental in the 1920s, today they are commonplace throughout the United States.

Olmsted Archives Lake Shore Highlands (Oakland, CA)In 1917, Olmsted Brothers were hired by Wickham Havens to prepare a site plan for an exclusive, restricted, upper-income residential suburb along the lines of San Francisco’s St. Francis Wood. The design was inspired by England’s “garden suburbs”, a residential park with greenery dominating.Olmsted Brothers laid out winding streets that followed natural contours, leaving natural areas and smaller park areas scattered throughout the residential area. To this day, Olmsted Brothers are to thank for the areas tree-lined, curvaceous, hilly blocks that are interspersed with open green spaces and strategic viewpoints.

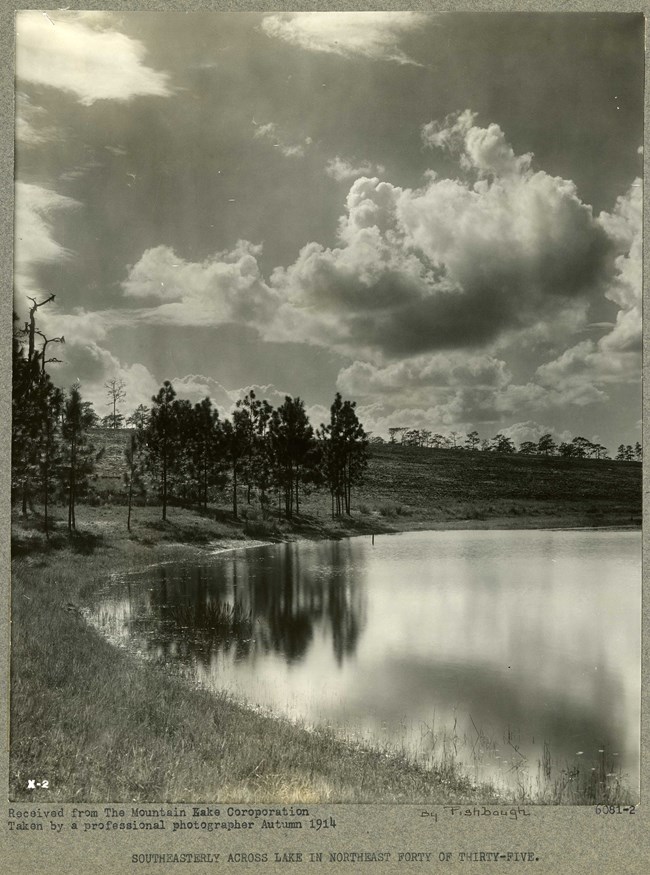

Olmsted Archives Mountain Lake Corporation (Mountain Lake, FL)In 1916, nestled among Florida’s liveliest hills, lakes, forests, and groves, Frederick S. Ruth of Baltimore purchased 3,500 acres of that lush land in the richest and most elevated real estate in the area. Ruth wisely employed Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to artfully lay out the 600 acres of the community that would become Mountain Lake.Olmsted Jr. centered the community around an 18-hole golf course and included Mission Revival and Colonial Revival-style houses, with a Mediterranean Revival-style club, which now serves as an Inn. At Mountain Lake, Olmsted Jr. understood the concept of beauty inside and out, and today, his grand vision remains a site to behold, as the community stands as an Audubon International leader in community sustainability.

Olmsted Archives Riverside (Chicago, IL)In 1868, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were commissioned to plan a unique, 1,600-acre community west of Chicago, dubbed Riverside. The goal at Riverside was to remove residents from the stresses of modern urban life as much as possible, allowing them to live in close harmony with nature while still retaining modern conveniences, such as a twenty-minute train ride to downtown Chicago.Riverside’s gently curving streets can be disorienting if you’re accustomed to the standard rectangular grid, and there are no square corners and no cul-de-sacs in the entire community. Olmsted prescribed well-built, well-drained roads with carefully curved lines and generous plantings in the hopes of creating an attractive and highly functional public grounds for rest and recreation. Respecting family privacy, Olmsted’s design facilitated interaction between neighbors by providing informal parks and playgrounds, as well as areas for strolling, boating, and other recreational activities. Unfortunately, the combination of the Chicago Fire of 1871 and a financial panic in 1873 ended the flow of funds and led to bankruptcy of the Riverside Improvement Company. Olmsted and Vaux both resigned over fee disputes, though they provided the village with a solid plan and infrastructure to build on.

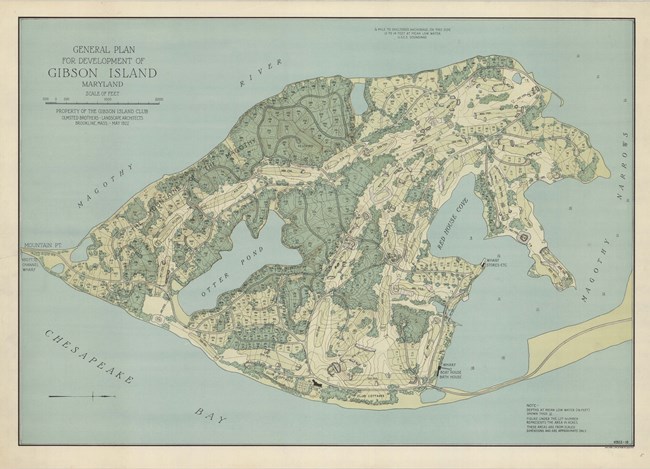

Olmsted Archives Gibson Island Development (Baltimore, MD)Olmsted Brothers was hired in 1922 to create a formal design for a community surrounded by water, jutting into the Chesapeake Bay. With John Charles taking the lead on the design, his plan emphasized the island’s natural topography while incorporating the native vegetation of the area.While Olmsted Brothers was responsible for the landscape, they also had ideas about the architecture of the community and called for a separation of areas depending on the style of the home, so that no styles mixed poorly, causing a dilution of the intended effect. Homes around Gibson Island are built in numerous differing styles: French and Spanish Eclectic, Gothic, Colonial, Tudor Revivals, Mission, and Art Deco. Around Gibson Island, roads take the form of paved, meandering paths, accommodating the 423 residential plots and two eighteen-hole golf courses Olmsted Brothers called for. However, financial constraint left the idea of the second golf course abandoned and trees were cut to increase views of the water, all to Olmsted's objections. While the Great Depression would alter the size of the development, to this day Gibson Island remains true to Olmsted Brothers’ vision for a recreational community, and their design provides a showcase for the Island’s 190 residences.

Olmsted Archives Roland Park (Baltimore, MD)In 1901, Olmsted Brothers were contacted about developing a residential subdivision, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. taking lead. As learned from his father, Olmsted Jr. believed that a community was an extension of the family. The challenge at Roland Park, Maryland was its challenging terrain.The steep slopes around Roland Park, which could have been a liability, turned into an asset for Olmsted Brothers. Olmsted Jr. chose to preserve the surrounding woodlands, citing the houses on slopes while using sensitive grading and construction techniques. Additionally, roads followed the natural curvature of the terrain, minimizing disruptive construction as well as saving some of the cost. Embracing the natural topography of the site, Olmsted Jr. created dramatic building lots and respected woodland resources. Cul-de-sacs terminating at the top of hills provided homeowners with spectacular views. By developing in a naturalistic way, Olmsted Jr. was able to enhance the picturesque effect of their design.

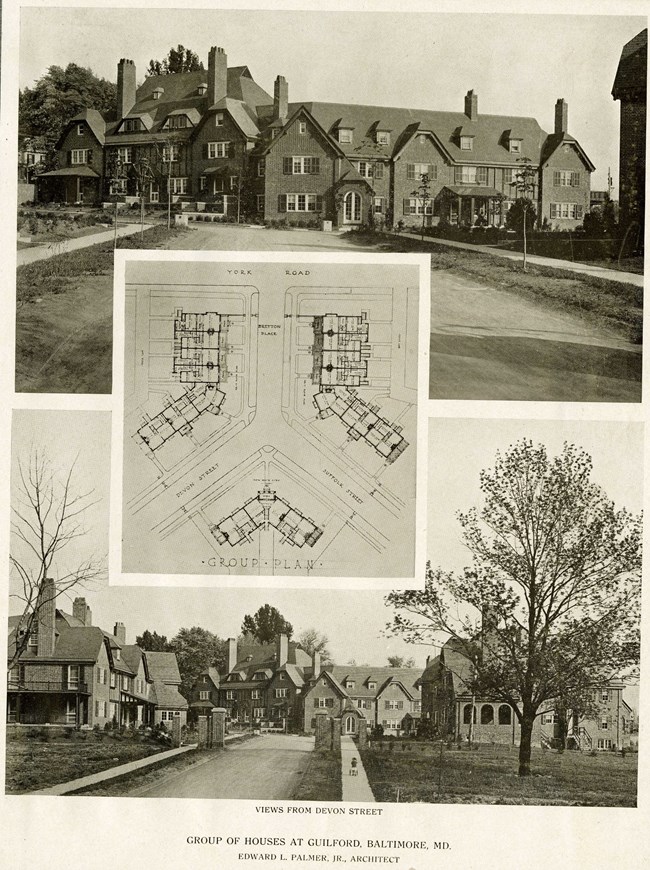

Olmsted Archives Guilford Land Company (Baltimore, MD)In 1911, the Roland Park Company purchased all the land belonging to the Guilford Park Company in the hopes to develop a suburban neighborhood just north of what was then the edge of Baltimore. 210-acres of rolling hills and oak forest were shown to Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., who would direct the planning and design of this new residential community.It was determined, and Olmsted Jr. agreed, that Guilford would be a garden suburb of the highest quality. When designing new communities, Olmsted Jr. placed great importance on “the separateness and internal integrity that would promote tranquility and give rise to the development of a sense of ‘shared community’ among their residents.” With the first lots being sold in 1913, Olmsted Jr. successfully introduced private parks to the area; little parcels of land in the center of Guilford blocks that elicit the idea of natural lands.

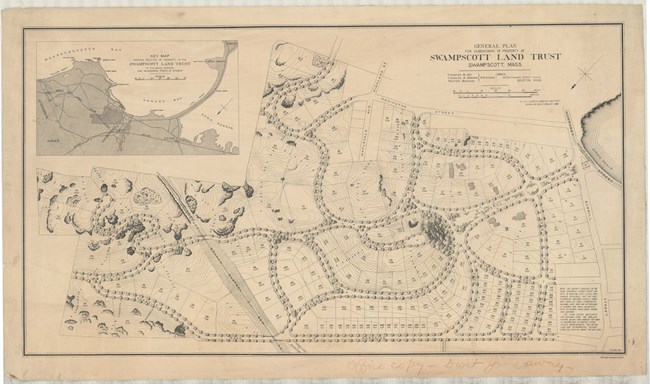

Olmsted Archives Swampscott Land Trust (Swampscott, MA)The 130-acre property, owned by Enoch Reddington Mudge, that would become the Frederick Law Olmsted Historic District in Swampscott, Massachusetts, was purchased in 1843. In 1881, Mudge died, and his properties were administered by trustees, who sold the land in 1887 to the Swampscott Land Trust.One year later, the Trust commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted to prepare a subdivision plan. The area, which already had open views of the ocean, was enhanced by Olmsted’s use of natural, curving roads complimented by beautiful houses. Houses in the area reflected popular architectural styles of New England for the times: Queen Anne, Shingle Style, Colonial Revival, Dutch Colonial, Bungalow, and American Foursquare. Many of the homes have survived, giving the district its character and significance from its key features and details. Monument Avenue is another Olmsted feature that has survived, with its sweeping symmetrical carriage road. Olmsted used three lot sizes to accommodate three sizes of homes and varying incomes and is one of the first to use deed restrictions to ensure continuity of community.

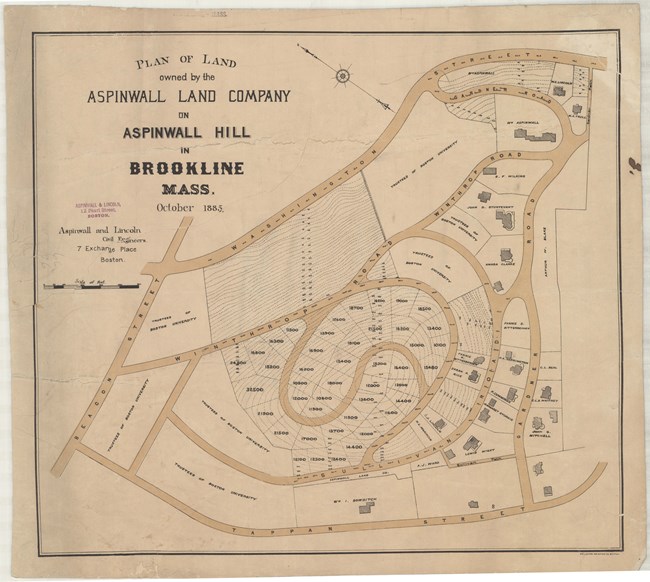

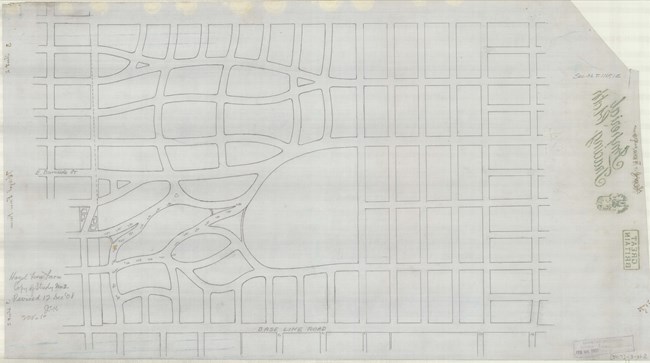

Olmsted Archives Aspinwall Hill (Brookline, MA)Before moving to Brookline, Frederick Law Olmsted would begin work on the town’s suburban community of Aspinwall Hill in the summer of 1880. William Aspinwall entirely owned the top of the hill while Boston University owned the land surrounding the hill. In 1857, a civil engineer created a plan for Aspinwall Hill subdivision, however it was never carried out. It was Aspinwall himself who decided to subdivide most of his land, and commissioned Olmsted to do it.It was Aspinwall himself who decided to subdivide most of his land, and commissioned Olmsted to do it. At the time Aspinwall and Boston University weren’t on the best of terms, with BU unsure if it wanted to partner with Aspinwall. Regardless, Olmsted’s original plan was a joint development, ignoring all property boundaries. Using a topographical survey to base his whole plan off, Olmsted created a spiral road system for the community. However, at Aspinwall Hill, Olmsted never made it past the study stage. There was a disagreement between landowners and Olmsted, leading to his services being suspended. Despite his plan not being implemented, the current design of Aspinwall Hill is a reworking of Olmsted’s original design. The most obvious left-overs from Olmsted’s design are the S-shaped roads, most visible on Addington Road and Colbourne Crescent. Olmsted was always thinking about how his landscapes would be enjoyed in the future, so he imagined the hill and how he would arrange homes on it, and what views would result from their placement. While many during Olmsted’s time complained of his curving roads, it created rhythm between open and intimate views, fostering a country feel.

Olmsted Archives Barton Hills Maintenance Corporation (Ann Arbor, MI)After work at Barton Dam, a hydroelectric project along the Huron River, began in 1913, the president of Detroit Edison Company began acquiring the surrounding land. Discussions arose about what should be developed on the land; with nearby steep ravines, it would be unsuitable for agricultural use.Olmsted Brothers were solicited to study the land and determine what should be developed on it. Firm member George Gibbs Jr. visited the site in 1915, submitting his concept for a suburban development months later. Commanding views of the nearby lake helped guide the plan, with more valuable lots being sited at higher points on the hill. Plantings were carefully curated to frame picturesque views. Olmsted Brothers continued to improve their design over several years, with John Charles and Frederick Jr. weighing in on various aspects. The firm designed Barton Shore Drive, parallel to Barton North Drive, which would "undoubtedly prove the most attractive when built as it will follow comparatively near the water and will command an uninterrupted view over the pool." Much of the development of Barton Hills was realized in the mid-1920s, when the first holes of the local golf course and country club were opened. Despite rapid development, Olmsted Brothers carefully planned the community to preserve and emphasize the land’s natural forms.

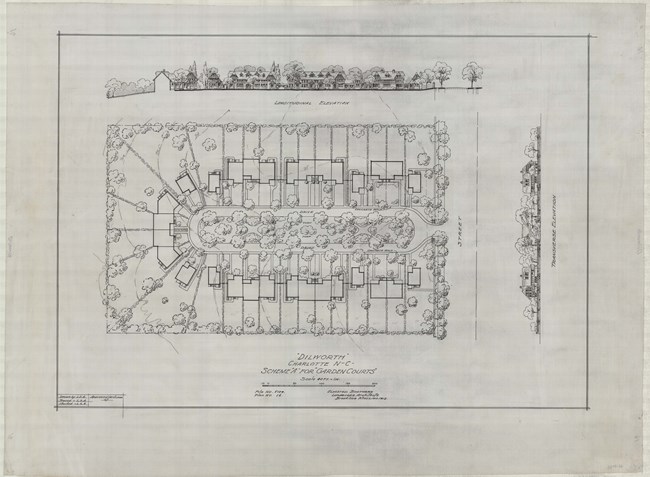

Olmsted Archives Dilworth (Charlotte, NC)While parks are often paid for by a town or city, a subdivision is often financed by a private citizen. Edward Dilworth Latta would be the private citizen who played a pivotal role in transforming Charlotte, North Carolina from a modest commercial center to an industrial and financial metropolis. While the city expanded, Latta wanted a suburban retreat from Charlotte.Latta would help form and become the Supervisor of Development for the Charlotte Consolidation Construction Company. The Four C’s, as it would be known, reached out to Olmsted Brothers in the summer of 1911, to design the street plan and landscape of their new suburban community, known as Dilworth, to honor Latta. It was Latta himself who would travel to Brookline, Massachusetts and strike an agreement with Olmsted Brothers: create a general plan for a 400-acre section at $5.00 an acre. The first thing Olmsted Brothers did after being hired was to direct Latta to hire a local engineering firm to meticulously survey and map the existing topography and conditions of the area. The second was to assign primary responsibility for the design of Dilworth of Olmsted Brothers associate Percival Gallagher. Land was broken into a northern and southern section, connected by a slim strip of creek. Olmsted Brothers had no issues with this, but insisted it was “essential, however, that the entire tract be considered”. The Olmsted Brothers plan tied the sections together with a curving grand drive, with smaller side streets branching off. Today Dilworth Road and the pleasant curving streets off Dilworth Road East and Dilworth Road West bear the mark of this outstanding design firm.

Olmsted Archives Hazel Fern Farm (Portland, OR)In 1909, the Ladd Estate Company sold its 462-acre Hazel Fern Farm to the Laurelhurst Company for approximately two million dollars, roughly sixty-five million dollars today. The Laurelhurst Company had plans to create a residential development on the land, using 444 of the acres to place 1,880 lots on. Olmsted Brothers were hired by the company to design the neighborhood.Unique from the onset, Laurelhurst had already set aside land for a park, school, and women’s home. The neighborhood took shape around the natural topography of the land. While many subdivisions use the easiest road methods, a grid format, Olmsted Brothers utilized a curving, tree-lined plan following the natural contours of the site. Green space was preserved for the common enjoyment of the community, and special care was given to the views a resident would get while walking through Laurelhurst’s streets. The idea that harmonious living could be achieved through landscape design can still be seen in Laurelhurst’s entrance arches, the tree-lined blocks and circular street patterns.

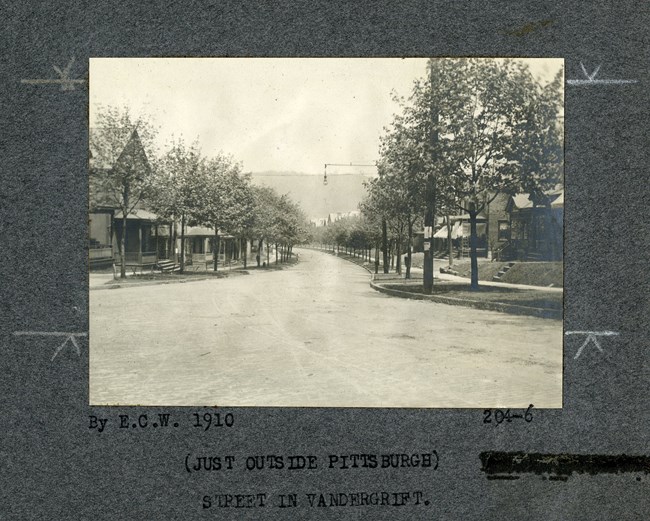

Olmsted Archives Vandergrift (Vandergrift, PA)As chairman of Pennsylvania’s Apollo Iron and Steel Company, George McMurty traveled to Europe to study their planned factory villages. On his return, he partnered with entrepreneur J.J. Vandergrift, as McMurty had plans of expanding his factory to nearby hilly farmland along the Kiskiminetas River. The dream was that factory workers would buy, not rent, their homes to ensure a committed labor force.In 1895, McMurty requested Frederick Law Olmsted to develop the plans for his factory village, but with Olmsted Sr. already retired, John Charles Olmsted took the lead at Vandergrift. John Charles wanted the factory life separate from town, so he located railroad and factory buildings on flatland by the river, while placing residential areas and main businesses on high ground, above the sound and smoke pollution. At Vandergrift, John Charles envisioned wide, paved streets that could drain easily, many single-family lots and small parklets, all curving around the hillside, following the river. John Charles’ plan was implemented so quickly that lot sizes were reduced to maximize house sites, and roads were narrowed.

Olmsted Archives Sage Foundation- Forest Hills (Forest Hills, NY)In 1909, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. partnered with architect and housing reform activist Grosvenor Atterbury to create a 142-acre community in Queens, New York City. In his design, Olmsted Jr. created streets differentiated by function. Olmsted Jr designed main roadways “for direct, ample, and convenient transportation,” while local, narrow streets were carved out of “quiet, self-contained and garden-like neighborhoods.” This helped to establish an arrangement of varied architecture and views.Also in Olmsted Jr.’s plan for Forest Hills were a variety of public green spaces. A central town Green provides a sharp contrast to the Queens landscape across the railroad tracks. Olmsted Jr also designed two smaller community parks for walking, relaxing, and festivals. In partnership with Atterbury, Olmsted Jr. were able to harmoniously mix landscape and architecture.

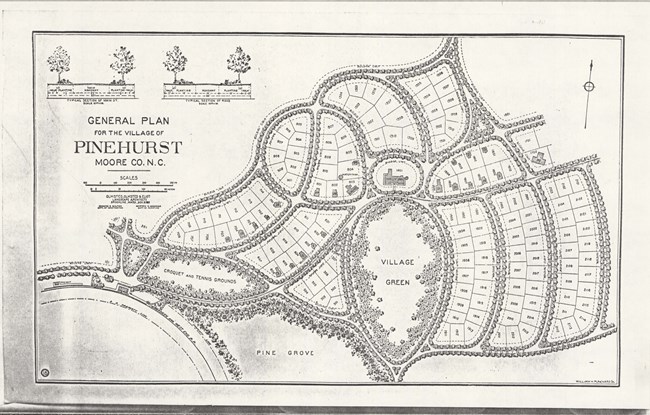

Olmsted Archives J.W. Tufts (Pinehurst, NC)In 1895, James Walker Tufts of Boston, Massachusetts commissioned Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot to design a planned resort community in North Carolina. Later named Pinehurst, it was one of the earliest planned resort communities in the United States. While the plan for Pinehurst was conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted, it was Warren Manning who carried it out.For Pinehurst, Olmsted introduced a system of curvilinear roads in the picturesque style, which he also applied at Riverside, Chicago, and many of his planned communities and subdivisions. Like Riverside planning, curved roads in Pinehurst creates an abundance of green space within the plan, as well as discouraging traffic, providing a quiet, peaceful neighborhood to locals.

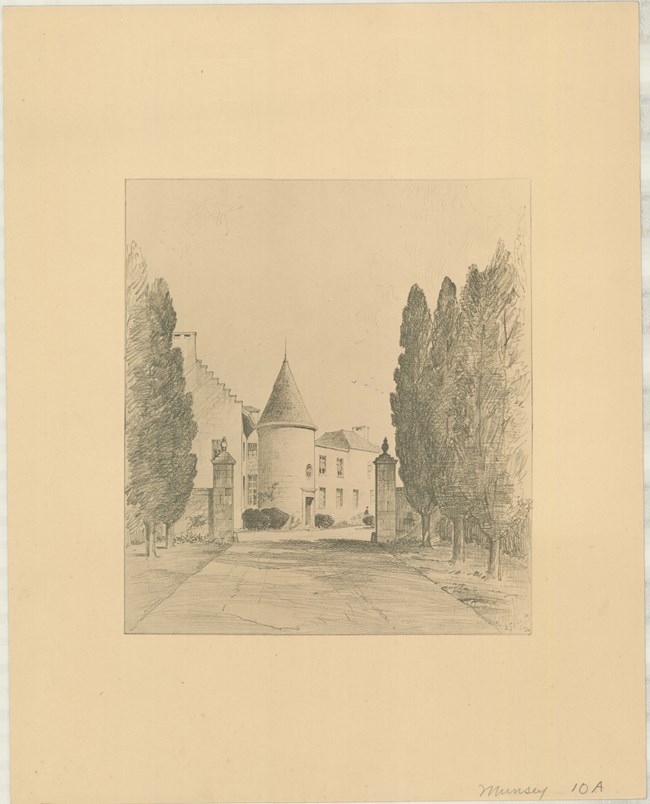

Olmsted Archives Munsey Subdivision (Manhasset, NY)After the death of multi-million-dollar author and publisher Frank Munsey in 1925, his estate and land were gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, on the condition that it would be divided into lots and auctioned off. President of the Museum of Art, Robert de Forest, worried about the planning of the neighborhood, and called on Olmsted Brothers in 1927 to improve the planning.Focusing on the area’s natural conditions and need of a community-centric design, Olmsted Brothers partner Edward Whiting created an efficient, aesthetically pleasing plan. To celebrate the connection to the Museum, tree-lined streets were named for artists, curving around the natural topography, designed with minimal access to the highway to avoid cut-through traffic. Within the Munsey Subdivision, five parks, a school, and three businesses were incorporated. By 1930, 162 homes were completed in the Colonial Revival style and work on a shopping center was underway. An attempt to put an eighteen-hole golf course failed and the land was returned for residential development.

Olmsted Archives Whalehead Club (Corolla, NC)In the 1950s, Olmsted Brothers were hired to develop a plan for the Whalehead Club subdivision in the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Detailed plans for the subdivision anticipated the highway extension from the south, however owner Ray T. Adams died in 1957, pushing the highway's opening till 1984. Corolla Island was the original draw of the property, with private residences for hunting guests built in 1925.

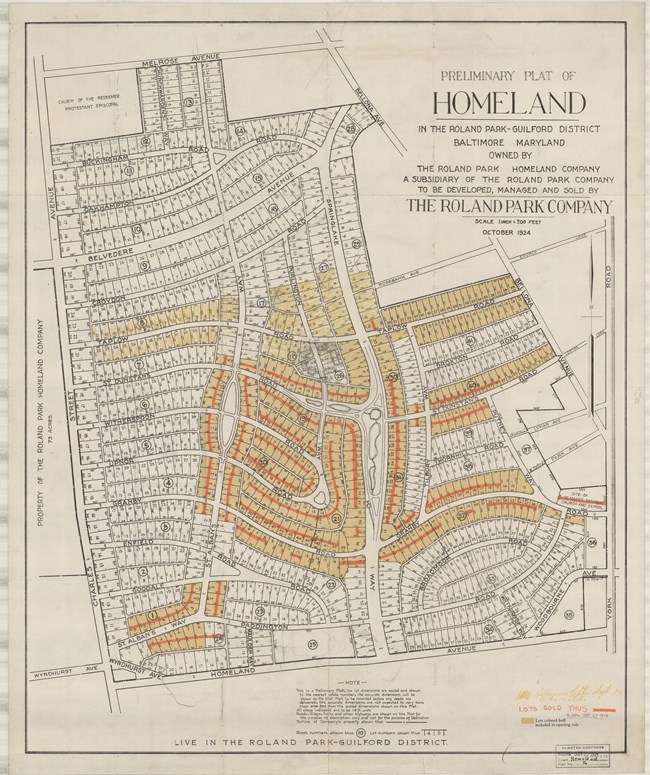

Olmsted Archives Homeland (Baltimore, MD)Following the success of Roland Park and the Guilford suburbs, the Edward Bouton-led Roland Park Company purchased land and began constructing a new residential community, dubbed Homeland. While Bouton was heavily involved, in 1924 he enlisted Olmsted Brothers to plan the suburb. Olmsted Brothers plan ensured sensitivity to the area’s existing landscape.A chain of stream-fed ponds already dug were retained and enhanced, becoming a defining feature of the community, with curving roads along the water. Olmsted Brothers also included a street hierarchy, where broad boulevards ran through the neighborhood, serving as gateways, with smaller streets insulating residents from the city’s noise and traffic. Lining the streets were sidewalks and large canopy trees, with hoses set back to create ample front lawns. Additionally, parcels were set aside for community uses such as parks, schools, and churches. In combination with careful street planning, Homeland also had underground conduits for telephone and electric cables, streetlights, and separated sewers from stormwater and sanitary water.

Olmsted Archives The Chimneys (Manchester, MA)In 1902, Olmsted Brothers were commissioned by Boston financier Gardiner Martin Lane to site a seven-chimney Georgian Revival summer home located on their 28-acres of land on Dana Beach, located in Manchester-By-the-Sea, Massachusetts. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. would take a leadership role in this design, working on the gardens for twelve years.The Lane Estate, referred to as “The Chimneys”, needed necessary grading and maintenance improvements, all of which were put in Olmsted's plan. In 1913, Olmsted Brothers created their General Plan for the Gardens, which included a work yard, tennis court, vegetable, and flower gardens, as well as terraces. In 1947, Edward C. Whiting was invited by the Lane family to visit and suggest improvements for the maintenance of the gardens. In the 1990s, a new owner restored the Olmsted garden to its original plan.

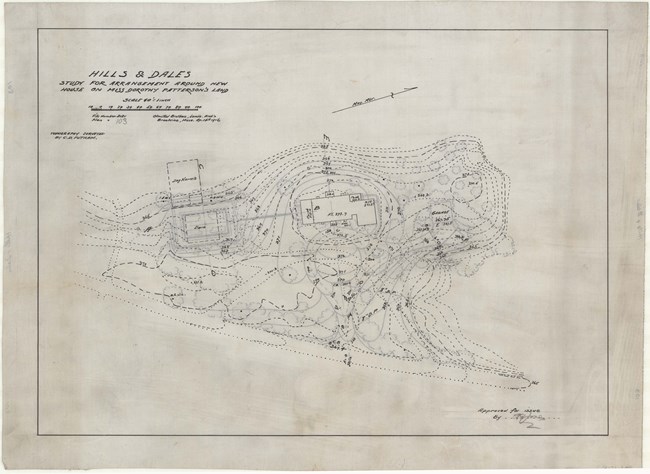

Olmsted Archives Hills & Dales (Dayton, OH)Of the 6,000 landscapes the Olmsted Firm designed over its nearly 100 years in practice, 274 of those designs are in Ohio, with 151 being in the Dayton area. 47 of these designs were constructed, one of them being the Hills & Dales subdivision. Olmsted Brothers began their relationship in Dayton around 1894, after being contacted by John H. Patterson, founder of the National Cash Register Company.Patterson wanted Olmsted Brothers to study his land and see if it was suitable to develop a park and suburb on it. In 1903, John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. began work on Hills & Dales, with firm associate Percy Reginald Jones. They wanted a park that fit seamlessly with the neighborhood it surrounded, providing passive and active recreational features with open meadows, bridle paths, fishponds, and campgrounds. In the end, Patterson gave 289 acres of parkland to Dayton, leaving the rest to develop a subdivision.

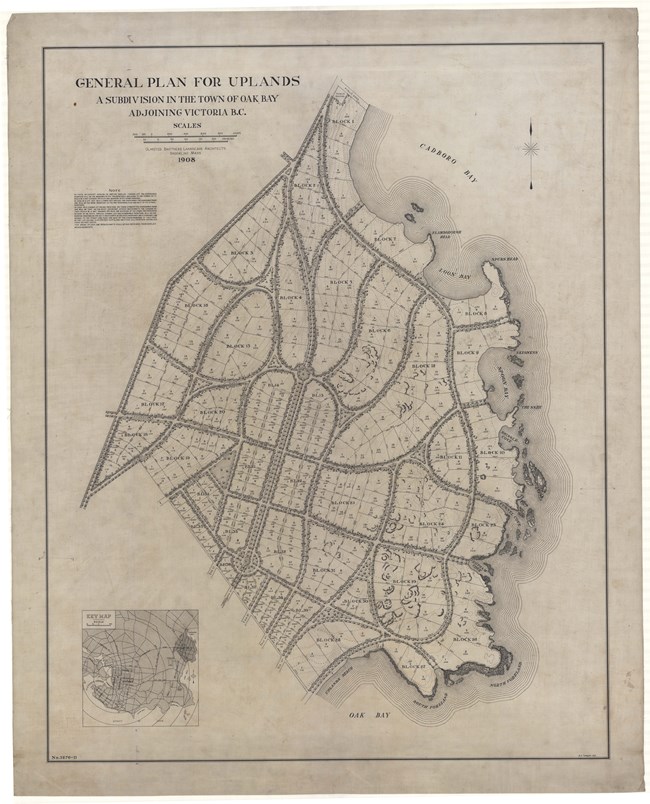

Olmsted Archives The Uplands (Victoria, British Columbia, CAN)With only two complete Olmsted-designed subdivisions in Canada, The Uplands is widely considered to be the first. Designed for real estate developer William Gardner, John Charles Olmsted of Olmsted Brothers worked on the design for The Uplands from 1907 to 1908. John Charles broke away from the traditional grid that guided many of Canada’s larger neighborhoods, utilizing a curvilinear street plan instead.John Charles worked to ensure roads fit with the area’s natural topography, and that significant features such as existing trees and views were preserved and protected. Despite a change in ownership in 1911, John Charles continued his work, focusing on deed restrictions to retain the area’s character, while Olmsted Brothers associate James Dawson was working on grading revisions and decorative light fixtures to line the streets. John Charles saw The Uplands as “unquestionably the best adapted to obtain the greatest amount of landscape beauty”.

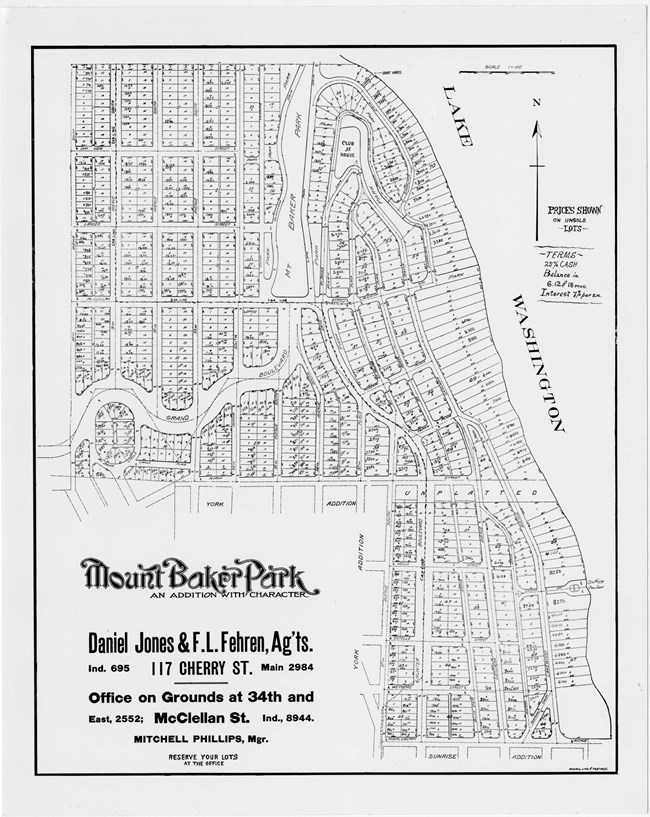

Olmsted Archives Mount Baker Park (Seattle, WA)As with many designs in the Pacific Northwest that the Olmsted Firm worked on, John Charles Olmsted was often in charge, and Mount Baker Park is no exception. Overlooking Lake Washington, John Charles developed a subdivision that left the shoreline untouched from development, later being used as a park and boulevard, which John Charles had suggested in his 1903 plan.Aside from saving land and views for residents, Mount Baker Park accomplished other aspects of the 1903 plan. By connecting the subdivision to several boulevards in Seattle, wide, winding swaths of green space were set aside for the community. John Charles saw the potential in Seattle to thoughtfully integrate a subdivision with open green space. Writing to one of his contacts in Seattle while discussing Mount Baker Park, John Charles stated that "I can say, and I do it with pleasure, that the project as a whole seems to be intelligently conceived, and if the proposed park features are finally adopted, it will certainly be to your credit in respect to the liberal treatment of the public in park matters, as well as in providing for future residents lands to be used in common, and in which remarkably beautiful views of and across Lake Washington, not to mention views of the Olympic Mountains in the other direction, can be enjoyed."

Olmsted Archives Licton Springs Park (Seattle, WA)The central attraction of Seattle’s Licton Springs Park subdivision was the inclusion of two mineral springs. When Olmsted Brothers first started work in 1907, their preliminary plan included a centrally located open green space, roughly in the shape of an ellipse, surrounded entirely by a roadway with lots for homes along the road. Olmsted Brothers also included a network of trails and interior roads that wound through the park.In addition to the mineral springs, Licton Springs Park was meant to include two ponds linked by streams, a forested interior, with paths and bridges. Unfortunately, the organic layout of the community, with its curving streets, homesites, and rustic park interior were never fully realized. From 1935 to 1960, the land had several different uses, from a farm to housing a small spa. In 1960 the park site became public land, with remnants of Olmsted Brothers scheme still present.

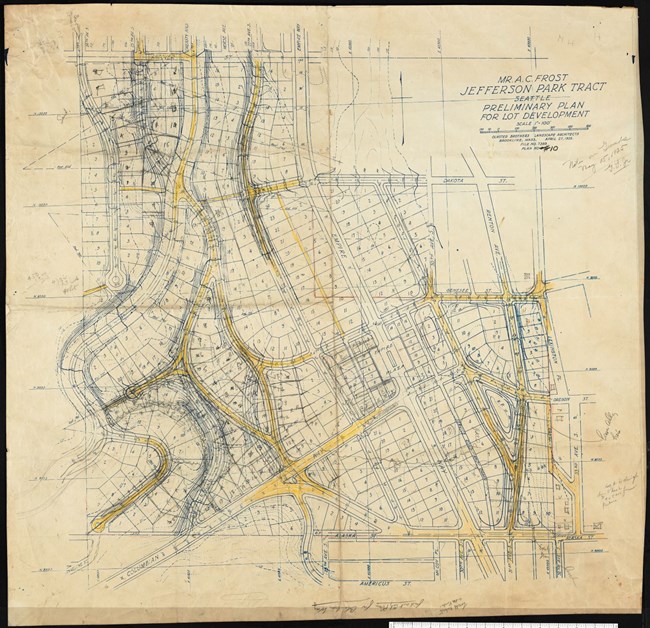

Olmsted Archives Jefferson Park Tract (Seattle, WA)Seattle miner and real estate developer Albert C. Frost hired Olmsted Brothers in 1924 to create a subdivision plan for his Jefferson Park Tract. While John Charles Olmsted usually handled designs in the Pacific Northwest, his death four years earlier gave associate partner James Frederick Dawson a chance to lead a design. Dawson had already done extensive work in Seattle, with John Charles, and he created several preliminary plans for the Jefferson Park Tract.The subdivision would encompass land next to Jefferson Park Golf Course, so Dawson explored several possibilities for the land. A preliminary plan of March 17th, 1925 included the nine hole golf course, a clubhouse, and an additional 101 lots for homes, many bordering the golf course. One month later, a new plan had lots along curved drives on hillsides, and straighter streets in the valley area. Unfortunately, Dawson’s plan was never carried out and the hillside portion of the tract was acquired by the City of Seattle. Today, what would have been Jefferson Park Tract is part of the Cheasty Greenspace, the largest wooded parkland located in the Rainier Valley.

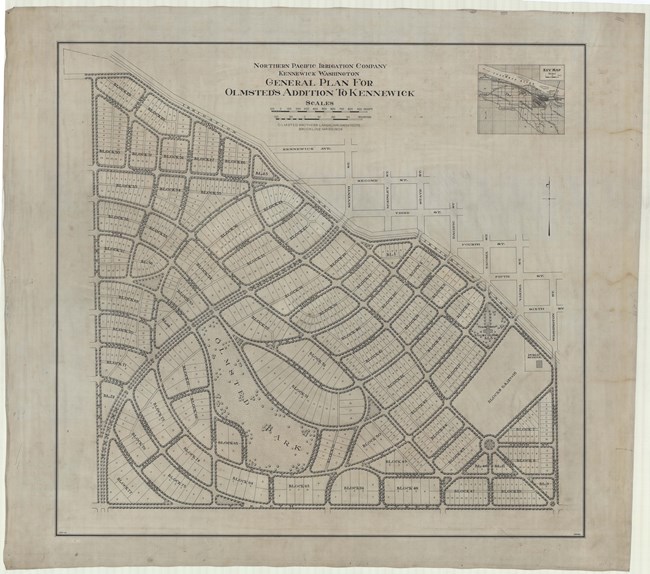

Olmsted Archives Northern Pacific Irrigation Company (Kennewick, WA)After viewing Olmsted Brothers’ design for the Uplands subdivision in Canada, developer David Gould asked John Charles Olmsted, often in charge of the firm’s Pacific Northwest designs, to develop a similar subdivision for a very different landscape in Kennewick, Washington. Known as the “Olmsted Addition” in hopes to boost marketing, an irrigation company as a client shows how water availability drove development in the arid West.Gould, who had once lived in Boston, was naïve to assume the Olmsted name would draw people to Kennewick, where large-scale agriculture was just beginning to gain ground. The Northern Pacific Irrigation Company’s subdivision saw John Charles creating 36 plans. Just like at The Uplands, curved, tree-lined roads and varied sized lots were found, the largest closest to a neighborhood park. Incorporating features adapted to the local conditions, John Charles noted that “I have always thought that where the climate was such that the parking strips could be easily taken care of and kept green it was rather a swindle on the public to take them out of the street in effect and add them in effect to the private lawns but it does seem that in this case where irrigation is required the advantages of doing so are sufficient to justify the arrangement.” Despite an impressive 1909 marketing campaign, few buyers were attracted to the subdivision. By 1912 there were less than twenty houses in the subdivision. Today, the “Olmsted Addition” is among several unrealized schemes the Olmsted firm lent their talents to.

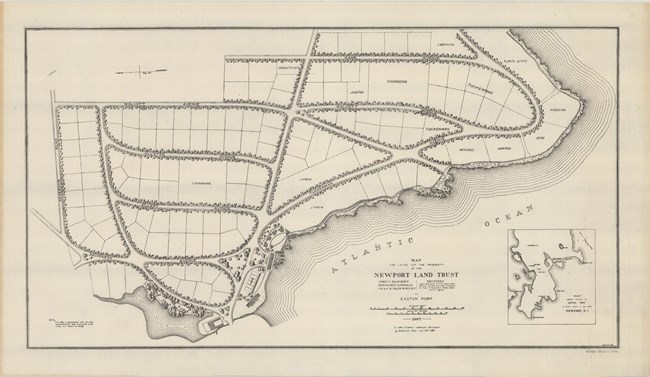

Olmsted Archives Newport Land Trust (Newport, RI)From 1880 to 1913, the Olmsted Firm played a significant role in the development and design of several private estates in Newport, Rhode Island. By the time work began on the Newport Land Trust, the firm was now known as Olmsted Brothers, and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. took a leading role on this project.In 1913, Olmsted Jr. prepared a detailed report proposing road and park improvements for Newport, as well as the layout for a residential community on Easton Point, right along the Atlantic coast. The tree-lined neighborhood included 104 single-family plots settled along coastal bluffs. Amenities included a bathhouse and tennis courts. Today the historic peninsula features colonial homes, many of which were restored in the 1970s.

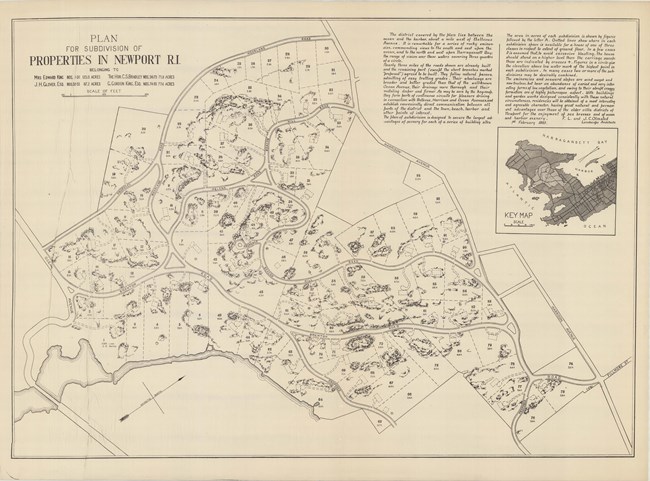

Olmsted Archives King-Glover Lands (Newport, RI)Three families, the Bradley’s, Glover’s, and King’s, all of Newport Rhode Island decided in the 1880s to combine their lands to create a residential subdivision. In 1884, they hired John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted to draw up plans for the community. The three families showed a strong willingness to enter into an agreement that would unite their lands for the foreseeable future.F.L. & J.C. Olmsted proposed connecting the three properties through a series of curvilinear roads and drives. Always with an eye towards the future, the road system was designed to be able to add several additional residences, built alongside a rocky route. Noting the uneven terrain of the land, the Olmsted’s envisioned that ““residences will be obtained with a most interesting and agreeable character, having great natural and permanent advantages over those of the older villa districts of Newport for the environment of sea breezes and of ocean harbor scenery.”

Olmsted Archives National Cash Register (Dayton, OH)Olmsted Brothers worked on the design for the National Cash Register subdivision in Dayton, Ohio from 1899 to 1932. Preparing plans for landscaping and layout, Olmsted Brothers worked to cohesively fit a community into a factory site. With dormitories, clubs, and recreation areas including a garden, ball playing field and open-air gymnasium, the subdivision reflected the company’s desire to provide quality accommodation and facilities to their employees. Despite the National Cash Register Corporation leaving Dayton in 2009, revitalization efforts for Olmsted Brothers’ design are still ongoing.

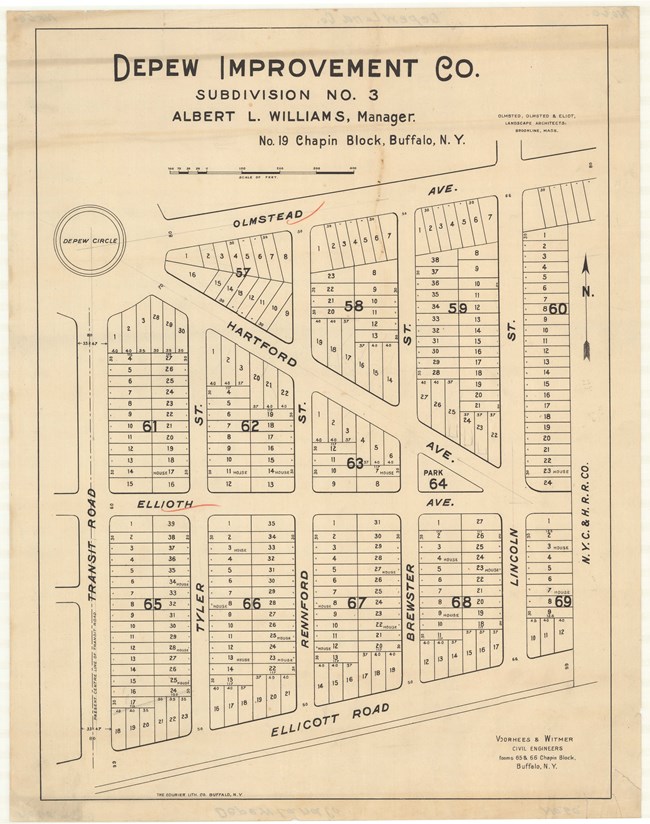

Olmsted Archives Depew Land Company (Depew, NY)In 1892, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot began work on a subdivision for Depew, a village of Buffalo, New York. Founded and named after local businessman Chauncey Depew, the area became a hub of industry, with the focal point being manufacturing and the New York Central Railroad. Unable to utilize their signature curvilinear street plan, the town was arranged in a traditional grid pattern, with avenues leaning diagonally.Three main avenues intersected streets, all stemming from a central roundabout called Depew Circle. The preliminary plan reflects the firm’s vision of integrating the railroad into the village. Several blocks would contain single family lots, with space along the railroad for shops and factories.

Olmsted Archives Colony Hills (Springfield, MA)Located on the border of Springfield and Longmeadow, Massachusetts, Colony Hills residential community was designed by Olmsted Brothers under the watchful eye of local attorney Charles H. Parson. Adjacent to Forest Park, Olmsted Brothers 1921 Preliminary Plan shows curvilinear roads, wide elevated sidewalks, and seventy-two lots for homes spread across seven blocks. Inspired by English villages, large single-family homes were styled in Tudor and Colonial Revival architecture. To preserve Colony Hills’ charm and aesthetic, Olmsted Brothers established a series of deed restrictions.

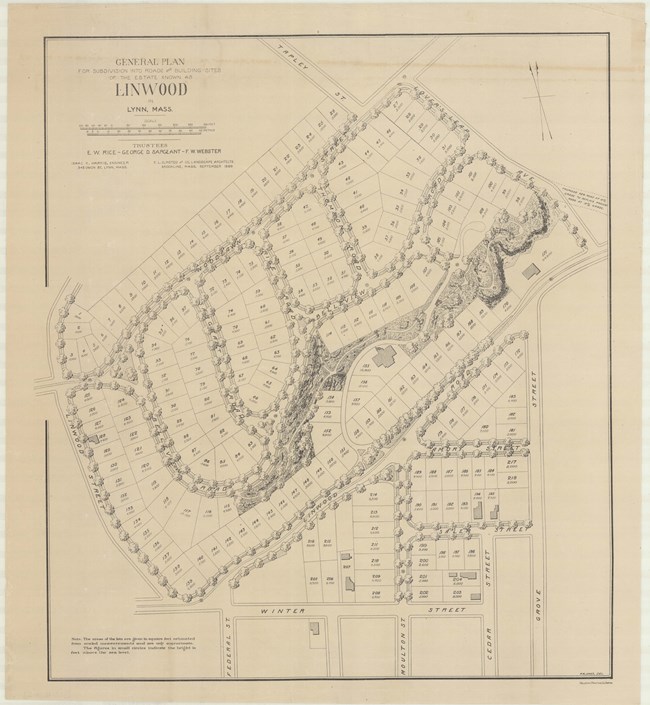

Olmsted Archives Linwood (Lynn, MA)John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted developed the Linwood subdivision on the estate of Philip Tapley, a hilltop property with views of striking features like Breed’s Pond and Lynn Harbor. With the site's steep topography, the pair faced challenges and had to make strategic design choices to maximize space on the hilltop plateaus. Plans show that roughly 218 lots were mapped to house large single-family homes. Unfortunately, Linwood was never developed. |

Last updated: June 26, 2024