|

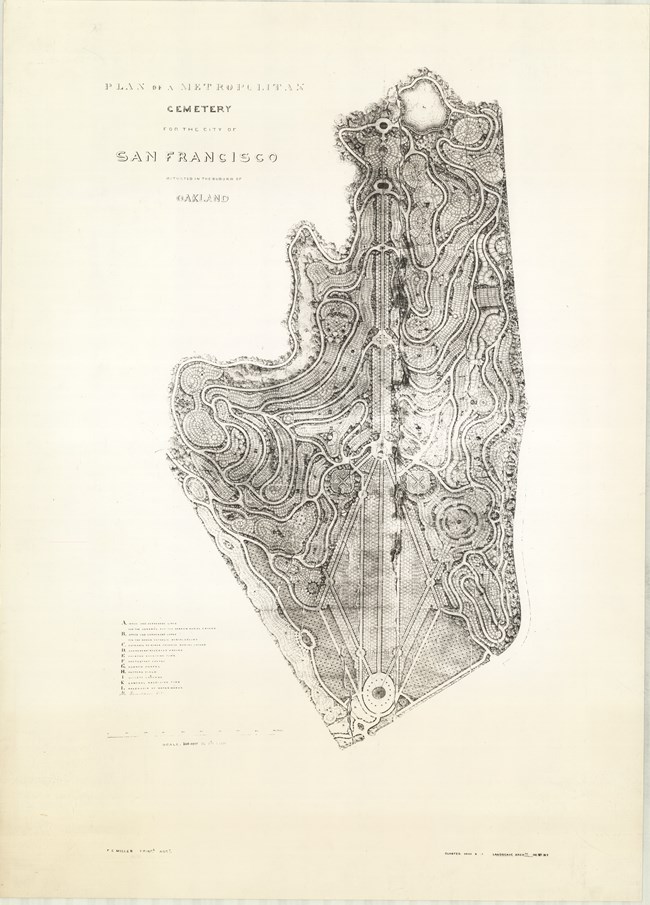

While the Olmsted firm provided designs for the settings of monuments of all types- in parks, public squares and other locations- the majority of the 275 projects (approximately 200 with at least one plan) in this thematic category relate to cemeteries and to individual burial lots, with the latter predominating. Most of these commissions took place in the 1920s. Designing landscaped grounds for the final resting places for many clients was an appropriate extension of the Olmsted firm’s work, as the home grounds, businesses and philanthropic endeavors of many of these individuals or families had been similarly graced by the Olmsted landscape aesthetic. Likewise, many of the monument and memorial projects not involving cemeteries were the result of work done on other commissions. In particular, the prominence of Frederick Law Olmsted JR. in the emerging discipline of city planning and his work for the Fine Arts Commission in Washington, D.C., especially after World War I, brought clients to the firm seeking tasteful solutions or redesigns for civic memorials. The Olmsted firm designed very few cemeteries as complete, separate from new projects. Frederick Law Olmsted set forth his concerns about cemeteries in his 1865 Preface to the Plan for Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, CA. For him there was an inherent conflict in creating a place of suitable expression of “those feelings, sentiments, and aspirations which religion and civilization make common to all in the presence of the dead” and achieving his ideal of landscape beauty where the ground was of necessity “cut up” into small divisions. As he later wrote to English landscape gardener William Robinson, “If art should do anything in a place of rest for our dead it should produce an impression of restfulness… I do not think I could lay out a burial place without making conditions about monuments such as I fear few but Quakers would be willing to accept.” Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California, was the major project of this sort that Olmsted undertook, beginning in 1864, with subsequent design work by the Olmsted Brothers in the 1940s. Among the examples of Olmsted Brothers cemetery projects were Hillside Cemetery in Torrington, Connecticut, and North Purchase Cemetery in Attleboro, Massachusetts. After World War II, the firm designed the American Military Cemetery in Cambridge, England. The later firm of Olmsted Associates designed Puritan Lawn Memorial Park, in West Peabody, Massachusetts, a project that had started during the Depression but was fully developed in the late 1950s-1960s. However, most of the Olmsted firm’s work involved improvements or additions to existing landscapes, some of these being nineteenth century rural cemeteries, which required expansion or accommodation to meet twentieth century needs, such as automobiles. The firm made extensive additions to the Memorial Cemetery of Saint John’s Church (listed as Saint John’s Memorial Cemetery) in Cold Spring Harbor and to Locust Valley Cemetery, both on Long Island New York; to Pittsfield Cemetery in Pittsfield, Massachusetts; to Kingsport Cemetery in Kingsport, Tennessee; and to the Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading, Pennsylvania. The firm also designed private cemetery grounds or tombs for several of their prominent clients such as the Kohler family in Kohler, Wisconsin; the Vanderbilt family in New Dorp on Staten Island, New York; and the Rockefeller family at Pocantico, New York (listed as Tarrytown). In some cases, these projects are incorporated under the residential estate job number, rather than being listed as a separate project. Likewise, there are cemetery grounds incorporated into some of the Olmsted Brothers’ campus planning, such as that for Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and for the Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. As John Charles Olmsted wrote in a series of articles in Garden & Forest published in 1888, cemeteries should be spaces set apart for the prime purpose of memorializing the dead in a respectful, contemplative setting. The Olmsted design credo of integrated whole compositions subordinating component elements, such as structures, within the landscape’s comprehensive aesthetic was particularly challenged to create an artistic unity over all the heterogeneous induvial united inevitable in a cemetery. Using plant groupings and working within topographic irregularities wherever possible, firm employees shaped burial lots into individual family “rooms” for dignified privacy, best exemplified by the lots for prominent clients such as the De Forests, the Coes, J.P. Morgan and others in the Long Island cemeteries, including those at Cold Spring, Cold Spring Harbor and Locust Valley. In a similar fashion, the Olmsted work for civic monuments and memorials involved the integration of the various structures into appropriate settings, either as individual focal units or within a park landscape. Some of this work involved statuary settings, such as the War Memorials at Capron Park in Attleboro, Massachusetts, and the Francis Scott Key Monument in Baltimore, Maryland. Other projects concerned the surrounds of prominent structures as in the Masonic Memorial to George Washington in Alexandria, Virginia, and the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial at Great Smoky Mountain National Park in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Moreover, not all memorial projects are listed in this thematic category (e.g., Memorial Hall in North Easton, Massachusetts, which is listed in the category Grounds of Public Buildings), so research inevitably involved making creative links to associated categories and projects. Text taken from The Master List, written by Arleyn A. Levee Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

Olmsted Archives Mountain View Cemetary (Oakland, CA)In 1863, Oaklands most prominent citizens joined together to establish a cemetery just north of the city. They asked Frederick Law Olmsted to begin his first work in California and design the 209-acre hillside property. Olmsted created his initial plan in 1864, though he would refine it over the next two years. He carefully selected drought-resistant plants that would line curving uphill paths, allowing for expansive views of the Bay Area, while also screening the cemetery from heavy winds. For his design, Olmsted drew on the philosophy of American Transcendentalism, which was popular at the time. As open space began disappearing in cities, people began flocking to cemeteries, which they saw as a replacement for the forests and fields taken up for development. Mountain View Cemetery stands out from the other cemeteries of its time because of Olmsted’s vision to look at man and nature and their relationship to one another. To compliment his winding paths, Olmsted brought in trees simple in form and color, though distinctive in shape, which helped create a setting of beauty and peace. He designed Mountain View Cemetery to serve as an example of a civilized life, where one both lives and dies in harmony with the environment. As families began buying up plots in the cemetery, it appeared the resting place would serve the affluent of the Bay Area, with many monuments being erected on the grounds. When Olmsted began work on Mountain View Cemetery, the land was 209-acres. Since then, it has expanded to over 226 acres, though with every new addition, there is sensitive treatment to Olmsted’s original design.

Olmsted Archives Arlington National Cemetery (Arlington, VA)With the end of the Civil War marked the need for several national military cemeteries. Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army and civil engineer Montgomery Meigs was tasked with developing Arlington National Cemetery.Meigs, who respected Frederick Law Olmsted, wrote him a letter five years after the end of the Civil War, asking his advice for landscaping national cemeteries. In an August 2nd, 1870 letter to Meigs, Olmsted said the design “should be studiously simple… [with] the main object…to establish permanent dignity and tranquility”. Meigs would resist Olmsted’s advice for a simple design, instead choosing to lay out the cemetery according to Victorian and Gilded age style standards. Olmsted also suggested “a sacred grove- sacredness being expressed in the enclosing wall and in the perfect tranquility of the trees within.” Meigs chose to take Olmsted’s advice, but not at Arlington. Instead, an area resembling sacred groves, graced by trees, and enclosed by walls would take form at Danville National Cemetery. From Olmsted’s advice, Meigs used trees indigenous to the cemetery’s region.

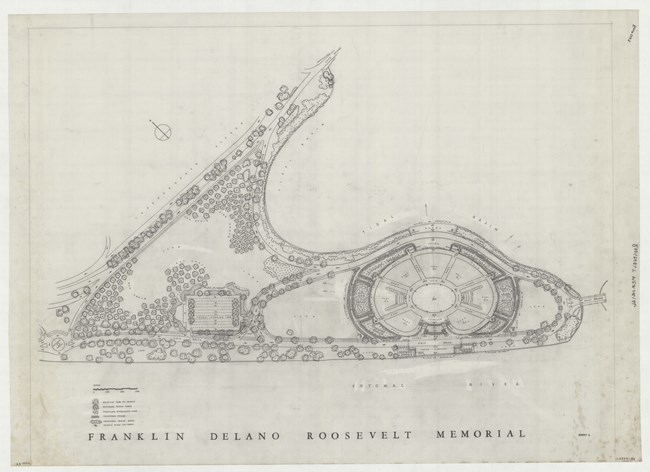

Olmsted Archives Roosevelt Memorial (Washington, D.C.)In 1932, an island was purchased with the idea of creating a memorial to the American political leader and renowned conservationist, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. What better way to honor someone so devoted to our natural spaces, then by dedicating one to them?Olmsted Brothers began preparing the plan for the memorial in May 1932, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. assuming primary responsibility, with the assistance of his associate Henry Hubbard. Olmsted Jr.’s goal was to create a restored woodland as a living tribute to the former president. The woodland was to be “a real forest closely similar in character to the natural primeval forests which once covered this and other of the Potomac islands”. With the assistance of the Civilian Conservation Corps, clearing of the island's non-native vegetation and planting of about twenty thousand native hardwood trees and shrubs took place between 1934 and 1937, only stopping because of World War II. Through Olmsted Jr. and the CCC’s efforts, the island was re-naturalized into a mature woodland. Olmsted Jr. and Hubbard’s original plan still guides the National Park Service in maintaining the landscape.

Olmsted Archives Pittsfield Cemetery (Pittsfield, MA)Western Massachusetts in the 1910s was not just a vacation spot for city dwellers, but becoming a bustling area itself, specifically Pittsfield. As the area grew space was needed, for both the living and the dead, and so the Olmsted Brothers were hired to layout new sections of the cemetery, which they did.In 1929, Olmsted Brothers returned to Pittsfield, MA at the request of Mr. and Mrs. Merle Graves. Olmsted Brothers had recently completed a nearby residential project for the family, and, pleased with their work, the Graves hired them to design their burial plot. The resulting design contoured to the natural forms of nearby boulders, surrounded by yew, barberry, and rhododendron, all of which are accentuated by near neon, vibrant, blooming crocuses.

Olmsted Archives Blaine Memorial (Augusta, ME)After the Civil War, James Blaine served as Secretary of State under three United States Presidents and became a dominant figure in American politics. After his death and burial at Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., Blaine, and his wife, who were highly revered by the people of Maine, were reinterred at Blaine Memorial Park.In 1920, Carl Rust Parker of Olmsted Brothers was asked to design the three-acre site situated just one mile from Blaine’s home, and was an area he and his wife enjoyed for strolling and meditation. Parker, who instead of college began work at Olmsted Brothers in 1901, served as a draftsman, planting designer and construction supervisor. Though Parker would attempt to start his own firm in Maine around 1910, he would return after World War One in 1919. In 1950, Parker became a partner of Olmsted Brothers, where he remained until his retirement in 1961. For Blaine Memorial, Parker’s plan included almost 2,800 plants in a horseshoe-shaped design with elms and two gravestones on the border. Parker also included a stone terrace overlooking the picturesque cemetery, accessible by granite steps going gently down the hillside. While many of the plantings have died, most of the design features remain.

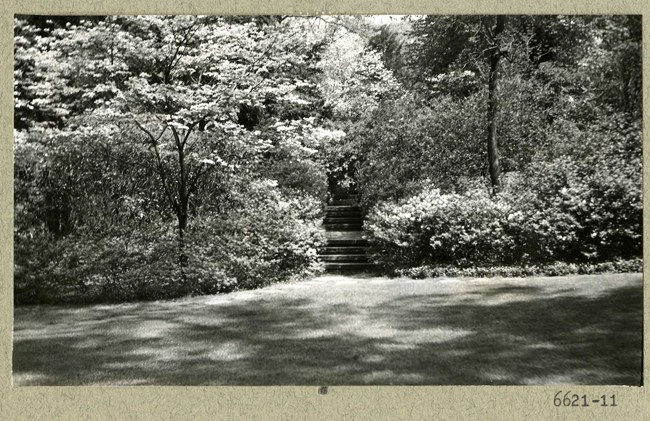

Olmsted Archives Saint John's Memorial Cemetery (Cold Spring Harbor, NY)When Frederick Law Olmsted was just becoming a landscape architect, unless you were a wealthy landowner, your only option for open green space were cemeteries. Because of this, many cemetery designs began to emulate a park-like setting.In the early 1900s, brothers William and Henry DeForest purchased 10 acres of land in the hopes to create their own cemetery in Cold Spring Harbor, NY. The land of their proposed cemetery sat right next to St. John's Church, which already operated its own burial grounds. Both DeForest brothers wanted St. Johns to administer their property but still have it in their name, which St. Johns refused. In the end, the DeForest brothers sold 7 acres back to St. Johns, keeping the remainder for personal use. After already hiring Olmsted Brothers to design each of their estates, the DeForest brothers again reached out to Olmsted Brothers. While the Olmsted Brothers were hired to design the DeForest brothers’ 3-acre plot, St. Johns realized that the esteemed landscape architecture firm was already in the area, so why not retain them to design their 7 acres of land. In the end, Olmsted Brothers continued working on new sections of the cemetery from 1918 to 1958. While these new layouts were much smaller and less park-like compared to the original designs of 1918, some prominent plot owners did like to go over the top with their design.

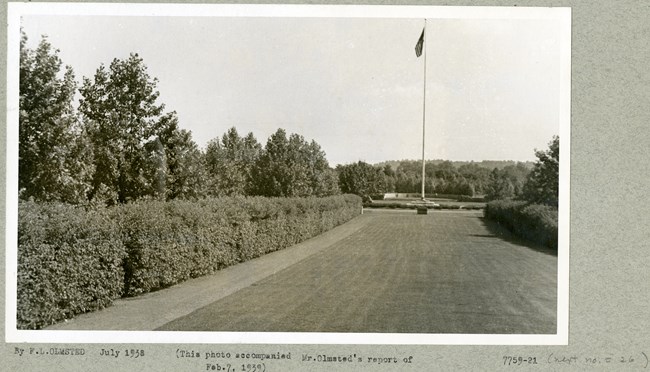

Olmsted Archives Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial (Lincoln City, IN)Remembering a President lost, all that he stood for, and how he evolved into the man he became, residents of Spencer County, Indiana recognized that Abraham Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks had been a formative piece of Lincoln’s life. It was decided that a suitable memorial should be erected for Nancy.From 1922 to 1938, the State of Indiana hired Olmsted Brothers to design a memorial site. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr ensured the landscape retained a strong North/South axis, allowing for processional and contemplative experiences. This axis would connect the gravesite of Nancy Hanks to a visitor center and open court. Olmsted Jr. took the lead in developing a plan to simplify the area around Nancy Hanks’ gravesite, whose landscape had been through many design changes over the years. A cruciform arrangement combining a main allée with plant beds was established, providing a “strong spiritual imagery”. Before briefly leaving, Olmsted Jr. proposed reforesting part of the site to provide a backdrop for the design. By 1983 Olmsted Jr. was called back to Spencer County, Indiana. The site needed a building facility and so Olmsted Jr proposed placing those buildings at the southern end of the allée.

Olmsted Archives Locust Valley Cemetery (Locust Valley, NY)In 1917, a group of wealthy men including J.P. Morgan, Robert Lovett, and Charles Coffin bought 25 acres of land next to the Locust Valley Reformed Church. Their hope was to create a special place for a burial, worthy of the wealth they had acquired in life.The group hired Olmsted Brothers to design a place of beauty and tranquility. As their father had taught them, Olmsted Brothers used the land generously to create a serene, parklike setting. When walking down the meandering paths, visitors see no graves, only towering oaks, maples, and endless rhododendrons. Only when you step off the path do you arrive at the grassy, intimate settings. These sections are family plots of 6 to 20 graves, all nestled in clusters of flowers and shrubs, with curved lines separating each grave. Over a hundred years later, those at Locust Valley Cemetery still work to preserve the landscape elements set forth by the Olmsted Brothers. The challenge is taking esthetic standards and applying them to modern, efficient land uses.

Olmsted Archives Vanderbilt Mausoleum (New Dorp, NY)A monument to America’s Gilded Age, the Vanderbilt Mausoleum was built for America’s wealthiest family of the time and combined two of the country’s greatest designers: Frederick Law Olmsted and Richard Morris Hunt.First planned by William H. Vanderbilt, it would be completed following his death by his son George W. Vanderbilt. Olmsted would design the grounds for the mausoleum and would include four landscape features: a broad terrace in front of the mausoleum, a hill surrounding the mausoleum, a stone arch to form an entrance, and a winding pathway connecting the entrance with the terrace. Olmsted and Hunt worked together on the design for the mausoleum terrace, and once completed, the Vanderbilt Mausoleum was hailed “the most magnificent tomb of any private individual” and “the most costly mausoleum in America” following its 1886 completion. The Vanderbilt Mausoleum was not Olmsted and Hunt's first collaboration, and it wouldn’t be the last. They had already worked on Central Park together and would go on to collaborate at the Chicago World’s Fair. Seeing how well they did on his family’s mausoleum, George Vanderbilt hired Olmsted and Hunt to design his estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

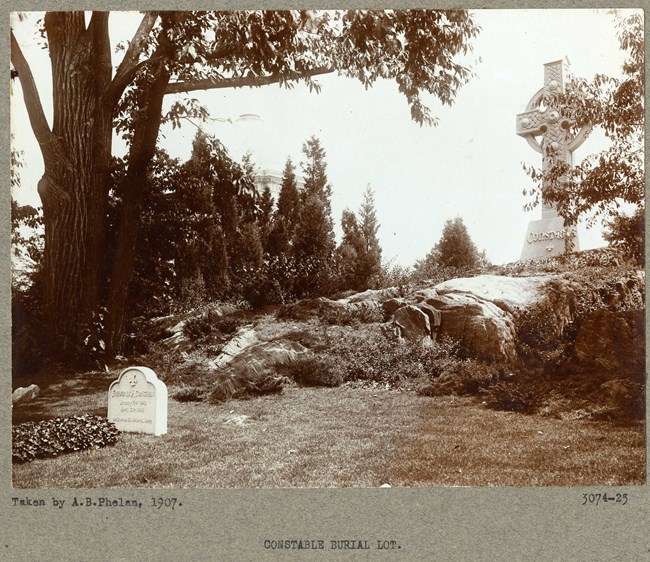

Olmsted Archives Woodlawn Cemetery (New York City, NY)Situated on 400 acres of rolling hills overlooking the Bronx River, Woodlawn Cemetery is noted for containing nearly 1,300 private lots, many designed by some of the most notable American architects and landscape architects.Woodlawn Cemetery is one in just a handful of Olmsted designed landscapes that feature some of the biggest names in the field. In terms of architecture, Woodlawn Cemetery brought in the talents of McKim, Mead, & White, John Russell Pope, Edwin Lutyens, John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings. As for landscape architects, Beatrix Jones Farrand worked on the Harkness Memorial Garden and the Milliken Memorial at Woodlawn Cemetery. Farrand was one of the founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architecture, with her most popular surviving project being Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. Ellen Biddle Shipman also designed the landscapes for three mausoleums at the cemetery. Olmsted Brothers handled the lot designs for Frederick Constable and Ernest Stauffen at Woodlawn, and in the 150 years since its creation, the cemetery is known for the serious collection of trees that spreads out around the burial lots. During Olmsted Sr.’s early years, cemeteries were one of the few places those not in the upper class could go for open green space. Olmsted Brothers created memorial gardens designed to provide comfort for those visiting their loved ones. No longer the only green space in town, cemeteries still reflect parks in many ways.

Olmsted Archives Grant's Tomb (New York City, NY)Before Ulysses S. Grant passed away, he requested that he be buried either at West Point, in the Illinois town of Galena he once called home, or New York City. After New York City was chosen as a burial site, the next task would be deciding where in the ever-expanding city.While many favored Central Park, a location at Riverside Park was chosen after Frederick Law Olmsted’s close acquaintance Samuel Parsons Jr. convinced Grant’s widow Julia that the Hudson River setting, with its sweeping panoramic views, was superior. Shortly after the burial, anxiety began to grow regarding the site of Grant’s Tomb, that it was inappropriate and would lend an unfortunate funerary air to this section of Riverside Park, which had been considered a gala promenade. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were particularly concerned. Nestled within the picturesque landscape of Riverside Park, Grant’s Tomb was designed to be approached by rail, water, carriage, and by foot. Grant’s Tomb is located atop one of the highest points along Riverside Drive, with surrounding formal walkways and parklands designed by Parsons and Vaux. To ease Olmsted and Vaux’s concerns, Vaux and Parsons proposed that the grounds of Grant’s Tomb be separated from the rest of Riverside Park with a newly cut road, which was done, ensuring Grant’s Tomb and Riverside Park could coexist in Olmsted’s vision of providing open park space unobstructed by the outside world.

Olmsted Archives George Washington Masonic National Memorial (Alexandria, VA)In 1915, the Washington-Alexandria Lodge of the Masonic Order purchased over thirty acres to build the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, and commissioned Olmsted Brothers to design the grounds for the memorial.Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. visited Alexandria, accompanied by Olmsted Brothers employee Carl Parker Rust, to get a sense of the site’s topography, well before any plans were created. Though young at the time, Olmsted chose Parker to lead the project, in part because he was a talented landscape architect, but most of all because he was a member of the Masonic Fraternity. Like Olmsted Sr. at Biltmore, who had recommended the orientation of the home to provide the most dramatic views, Parker also gave a recommended orientation for the Memorial: east, for ritualistic purposes. Parker created a dramatic entry to the Memorial, including a curvilinear drive and axial stairway, both ending at a grand plaza. While some of Parker’s plan, specifically the planting, wasn’t implemented, features that were executed are vital to experiencing the Memorial. While more prominent features include the terrace cascading down the hillside and the stone retaining wall, Parker also dealt with more mundane features like draining, roads, the general maintenance of the grounds, and others.

Olmsted Archives Washtenong Memorial Park (Ann Arbor, MI)Olmsted Brothers would landscape several projects in the Ann Arbor, Michigan area before, in 1929, being called to design a cemetery just over forty-acres North of their Barton Hills subdivision. The topography of the land allowed for proper drainage, and most of the acreage was without any trees. While locals wanted the land to be divided into four, ten-acre sections, Olmsted Brothers had other ideas.The 1931 General Plan for Washtenong Memorial Park used a curvilinear road system following the natural topography of the site. An axis for the chapel, fountain, and service area cut across the interior curvilinear drives, providing a contrast of uses. The areas between plots were suitable for family lots or mausoleums, and plantings of evergreen trees together were used to direct views. From correspondence, we know that Olmsted Brothers planting list was followed according to the suggested location and species. As late as 1959, members of the Olmsted Firm were still in contact with those managing Washtenong Memorial Park.

Olmsted Archives Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (Gatlinburg, TN)Olmsted Brothers were hired by the National Park Service in 1938 to create a memorial to John D. Rockefeller’s wife Laura. With only a budget of $20,000, and working in harsh winter conditions, Olmsted Brothers tasked partner Henry Hubbard with the design.Hubbard was tasked with transforming the “nose of a little hill” into a spiral of two terraces climbing up the hill’s slope. When it came to construction for the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, the Civilian Conservation Corps were commissioned, working until 1940. When development began, Hubbard created a clay model of two semicircular stone block terraces hugging the face of the hill, connected by steps leading to a lookout. Models were created at the request of a client and were almost immediately taken apart after completion of the design. After Hubbard created his model for the Spelman Memorial, he took a light and tracked the path of sunlight, to ensure that light shined on the memorial. This extra attention to detail is what helped make the Olmsted firm so prolific.

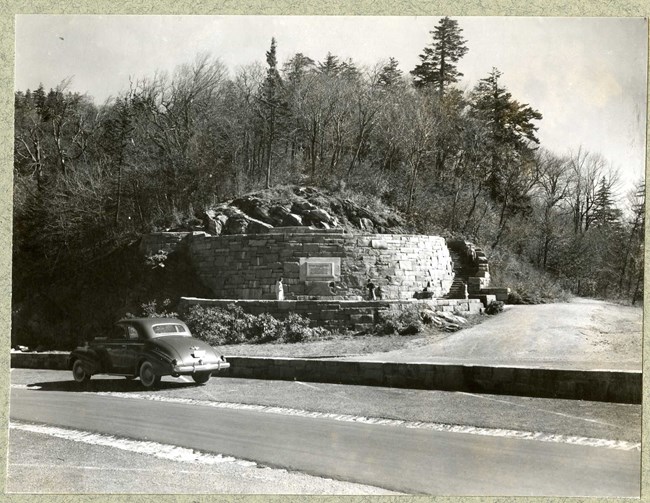

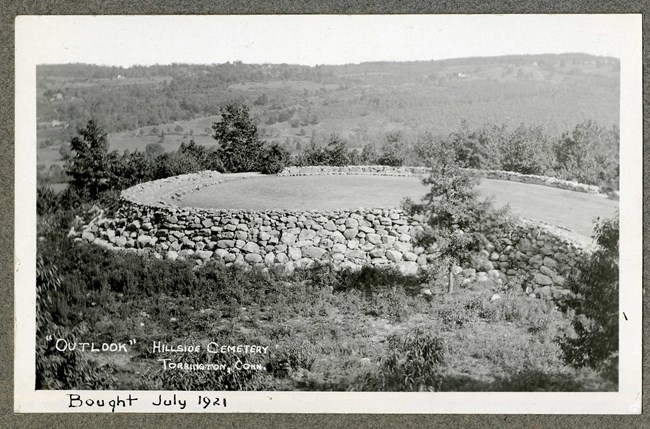

Olmsted Archives Hillside Cemetery Association (Torrington, CT)The Olmsted Firm’s involvement at Hillside Cemetery in Connecticut began in 1907 and spanned the next sixty years, with firm partners like James Frederick Dawson, Percival Gallagher, Edward Whiting, and Joseph Hudak all adding to the design. Gallagher performed the original assessment of the property, praising the natural scenic views provided from the wooded hill site, with good views of neighboring land.Gallagher suggested that clearing and grading should be done with a view to preserving and protecting the land's memorable characteristics. Monuments were to be designed with tasteful details to avoid monotony and an excess of ornamentation. As for plantings, trees and shrubs would be spread out among the plots and monuments, with rock outcroppings reserved for scenic views. |

Last updated: June 14, 2024