|

The design of residential grounds constituted the largest category of properties for the Olmsted firm over the entirety of its practice, with more than 3,000 listings, of which about 2,000 generated at least one plan. Although parks and park systems were initially the major area of endeavor for Frederick Law Olmsted and his partners, domestic design increasingly became an important component of the practice as transportation improvements extended suburban enclaves beyond city boundaries. From the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first three decades of the twentieth century, commissions for private home grounds steadily increased so that, for the 1910-130 decades alone, they numbered more than 1,000 projects. For Frederick Law Olmsted, the concern was to create tasteful domestic settings, artistically coherent, appropriate in scale and unblemished by extravagant materialistic displays. He sought to enhance natural site features to create a series of separate spaces, giving the home its distinctive character, much as he did in his own domestic landscape at Fairsted in Brookline, Massachusetts, making the two acres seem more expansive. These same design criteria influenced planning for larger estate properties, though for these he often included a greater utilitarian purpose, such as forestry (J.C. Phillips/Moraine Farm in North Beverly, Massachusetts), scientific farming (W.S. Webb/Shelburne Farms in Shelburne, Vermont, which is listed in Burlington, Vermont) or horticultural education with forestry at a uniquely monumental scale of thousands of acres (G.W. Vanderbilt/Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina). While essentially retaining these criteria in their residential work, the Olmsted Brothers firm was frequently called upon to include more decorative and formal elements- pergolas, pools, tea houses, etc.- in their estate practice, which flourished in the post World War I years. The client list reads like the Who’s Who of American society, national civic and business leaders as well as prominent individuals from cities across the country. The nexus of grand estates on Long Island for many of these wealthy clients (e.g., Otto Kahn in Cold Spring Harbor, New York; William R. Coe’s Planting Fields in Oyster Bay, New York; and J. E. Aldred in Glen Cove, New York) reflected similar work, some begun by the earlier firm, for clients in Newport, Rhode Island (e.g., Anson P. Stokes in Newport, Rhode Island, and I.N. Phelps Stokes in Greenwich, Connecticut). The firm designed grounds of clients’ city homes and for their country places (e.g., Misses Norton in Louisville, Kentucky and Hendersonville, North Carolina). The firm’s extensive planning for residential subdivisions and resort communities across the country led to numerous private commissions within these enclaves. In Seattle, work for The Highlands/Seattle Golf & Country Club generated eleven other residential commissions within this gated community; for the Palos Verdes Syndicate in California the firm worked on nineteen individual projects; for Yeamans Hall in Charleston, South Carolina, on another seven homes while for the Mountain Lake Corporation in Mountain Lake (Lake Whales), Florida, the client roster grew to more than eighty individual listings. As the economy changed, the Olmsted Brothers firm was called back by several of these substantial clients to plan for subdividing what had once been grand estates. In particular, the original work done in the first decade of the twentieth century for the restructured Tudor mansion for I.N. Phelps Stokes in Greenwich, Connecticut, became a multi-plot high-end residential community, Khakum Woods. This subdivision, begun in the 1920s, was carefully crafted to retain the original landscape character. Likewise, Fernwood, the original Brookline, Massachusetts, estate for Alfred Douglas, was divided into smaller units. In both examples the documents for both the single property and the subdivision are found under the same job number. However, the Olmsted firm also designed residential grounds on smaller lots for worker housing within Subdivisions and Suburban Communities, as in the multiple projects for National Cash Register in Dayton, Ohio, or for the Beacon Falls Rubber Shoe Company in Beacon Falls, Connecticut, among other such commercial projects. This residential work is incorporated within the documents under the job number for the larger project. Therefore, as extensive as this thematic category is, there is still more related research to be done to extract the full range of the Olmsted firm’s domestic work from the archival records. Text taken from The Master List, written by Arleyn A. Levee Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

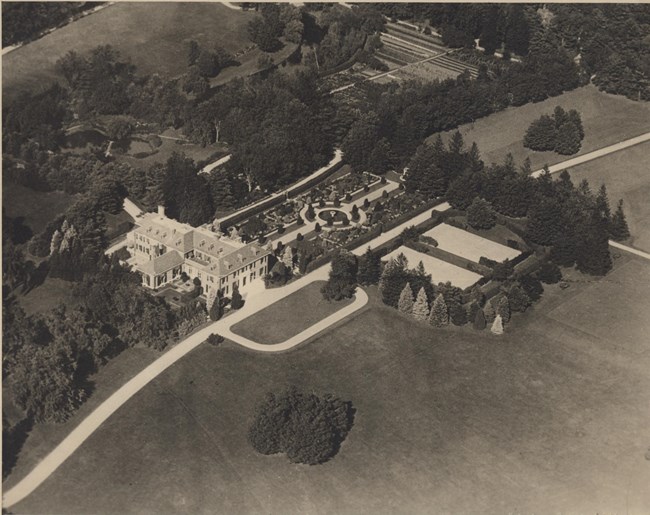

Olmsted Archives Crane Estate (Ipswich, MA)In 1910, Richard T. Crane, Jr. was also a man of exorbitant wealth, though he didn’t move to Ipswich to stir up anything. Crane inherited the top post in his family’s manufacturing company and expanded it into modern bathroom fixtures. Crane even had an exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair, where he displayed “the world’s largest shower”. Crane purchased the 165-acre plot of land and knew exactly what he wanted: a bowling green, tennis court, maze, log-cabin playhouse, golf course and deer preserve. Crane and his family also ran a self-sustaining farm with livestock, an orchard, and dense vegetable and rose gardens, which space needed to be made for. Crane was building his summer getaway during the country place era, a period of landscape architecture design where wealthy Americans commissioned extensive gardens at their country estates, emulating European gardens. To this day, Crane Estate is one of the last surviving, intact American estates from this era. Crane brought on the most prominent landscape architects of his time: Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and John Charles Olmsted, of the Olmsted Brothers firm, and Arthur Shurcliff, who had left the Olmsted firm in 1904 to start his own. Shurcliff was mentored by Charles Eliot, who like himself, left the Olmsted firm to open his own. The Olmsted Brothers designed a series of Italian gardens for the Crane Estate, all enclosed by evergreens, the same one’s you see lining the Grand Allée, where Daryl Van Horn chooses to have lunch. Though the Olmsted Brothers started work on the Grande Allée, they were dismissed by Crane and work was handed over to Arthur Shurcliff. From 1913 to 1915, Shurcliff worked on the half-mile long formal mall leading from the Crane Mansion to the Atlantic Ocean. In 1949, the Crane family donated the land to the Trustees of Reservations, which was founded by former Olmsted firm employee and mentor to Arthur Shurcliff, Charles Eliot.

Olmsted Archives Biltmore Estate (Asheville, NC)Frederick Law Olmsted knew George’s father, William Henry Vanderbilt, when they both lived on Staten Island. Olmsted had already done several projects for the Vanderbilt family when George approached him in 1888, asking for advice on the 120,000 acres of North Carolina property he’d just purchased. At the age of 66, Olmsted made his first journey to Asheville to visit George Vanderbilt, then 25 and the recent inheritor of $13 million (around $350 million in 2020). Unlike many projects Olmsted had worked on, Vanderbilt had the money to carry out his designs, and he knew exactly what he wanted: an English manor style estate. “The soil seems to be generally poor. The woods are miserable, all the good trees having again and again been culled out and only the runts left. The topography is most unsuitable for anything that can properly be called park scenery. My advice would be to make a small park in which you look from your house, make a small pleasure ground and gardens; farm your river bottoms chiefly and…keep and fatten livestock with a view to manure and…make the rest a forest” -Frederick Law Olmsted in his letter of recommendation to George Washington Vanderbilt Olmsted was able to convince Vanderbilt that the land would be better suited with a grand garden area close to the house and turn the remaining acres into a forest, providing the home with spectacular views. In Olmsted’s final project, he built a nine-mile arboretum that went from the house, to the French Broad River, and back up to the house again. He also planned the entry way to the Biltmore as a pleasure drive, passing through a “natural forest”. That natural forest contained clusters of trees that purposely blocked the view so that visitors would be shocked when the curtain of the forest was pulled back and you could finally see the house. Despite ill health and the pressure of the Chicago World’s Fair, Olmsted traveled by rail several times to Asheville, ensuring his designs were being followed. He felt the transitions between formal and natural gardens were important to differentiate, as was the use of native plants, and a balance of small trees and large shrubs. Following Olmsted’s suggestions, Vanderbilt hired trained forester Gifford Pinchot to develop a management plan for his land. Together with Olmsted, they founded America’s first large scale managed forest, and the cradle of U.S. forestry.

Olmsted Archives Duncan McDuffie Estate (Berkeley, CA)Duncan and Jean McDuffie were two extremely influential residents of 20th century Berkeley, California, and deserve credit for the shaping of today’s city and environment. When deciding who would do the garden design for their new estate, it made sense they chose the firm that represented the highest standards for their time: Olmsted Brothers.Olmsted Brothers favored the extensive use of both California native plants and those that grew in the Mediterranean climate for their design at the McDuffie estate. The design mirrored Spanish Colonial Gardens that were often furnished with varying styles of pottery, outdoor furnishings, pools, and fountains. Having already perfected the art of landscapes with wildflowers and alpines as borders, Olmsted Brothers carried out a similar design for the McDuffie’s. The couple was so pleased with the Olmsted Brothers’ design, they would go on to help them get the commission for East Bay Park.

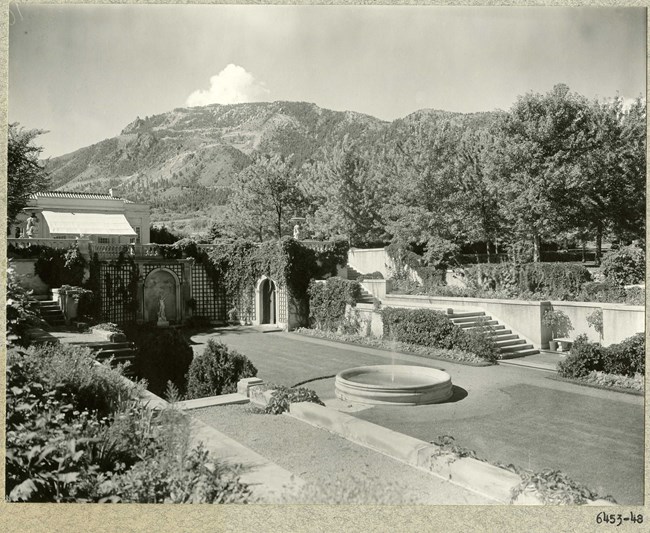

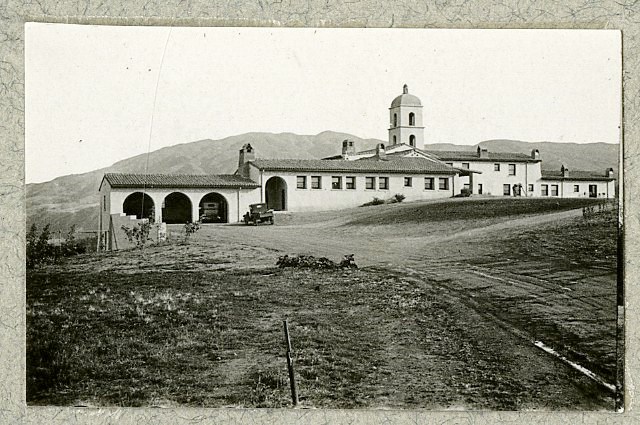

Olmsted Archives El Pomar (Colorado Springs, CO)By 1916, Olmsted Brothers were commissioned by Spencer Penrose to design the grounds for his new resort, the Broadmoor Hotel, and since they were in the area, would also design the grounds for Penrose’s own estate, dubbed El Pomar.Penrose asked Olmsted Brothers for both designs to be artistic and memorable. Today, the grounds of El Pomar are home to hummingbirds and moths that hover around roses and petunias. Red tiles under the porch provide a shady spot to listen to bubbling water from three nearby fountains. As fall causes the leaves to change, herds of deer and geese graze the orchard at El Pomar. Even as the grounds of El Pomar were under construction, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr S influence in conservational ideals was reaching its climax. While working in Colorado Springs, Olmsted Jr.’s Organic Act was passed, and the National Park Service was created. The beauty Olmsted Brothers left at El Pomar still exists today and will continue to benefit generations of Coloradans. Olmsted Brothers’ design inspired nonprofit and social leaders to preserve the grounds of El Pomar.

Olmsted Archives Khakum Wood (Greenwich, CT)Returning to their fathers home state, Olmsted Brothers would work in partnership with architect Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, who had purchased about 180 acres of farmland in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1903, to design Khakum Wood.Stokes bought the backcountry farm with the idea of subdividing the land into a series of houses. He contracted Olmsted Brothers to create the layout for the residential development. Olmsted Brothers respected the natural topography of the land, which was accentuated with rock outcroppings. With irregular parcels of land ranging in size from less than one acre to over four, Olmsted Brothers chose to include circular roadways, to give more depth to the land. Khakum Wood was planted with mountain laurel, dogwoods, azaleas, and evergreens, with a lake as the centerpiece. Today's Khakum Wood community still abides by the Olmsted curves.

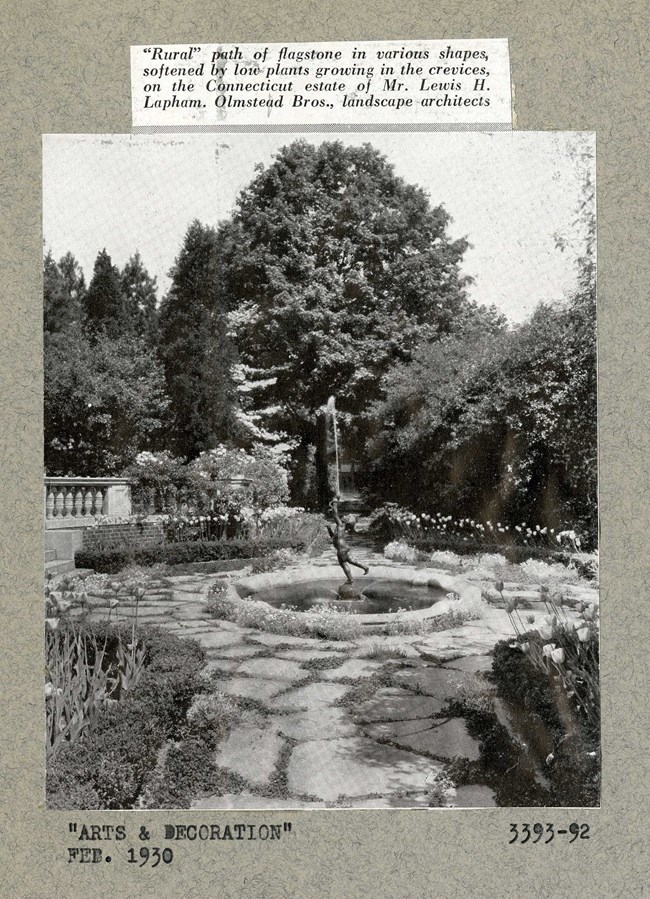

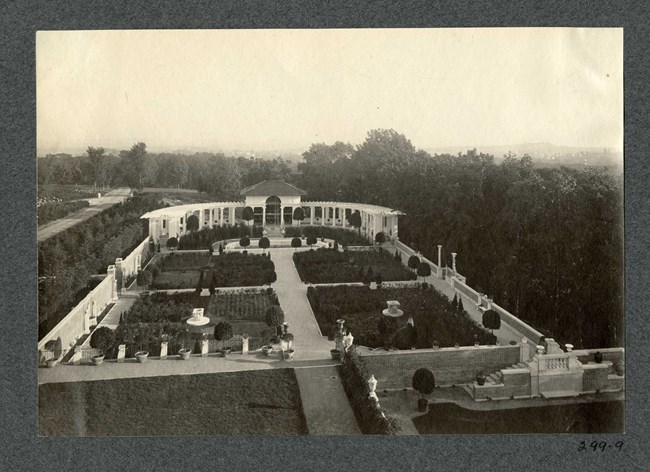

Olmsted Archives Waveny Park (New Canaan, CT)After purchasing Thomas Wells Hall’s summer estate in New Cannan, co-founder of the Texaco Oil Company, Lewis Henry Lapham renamed the estate Waveny, and expanded it from 280 acres to 450. Lapham tore down Hall’s home to build a new one, and had the grounds redesigned by Olmsted Brothers in 1904.With the project being led by John Charles Olmsted, the most distinct design at Waveny was the parterre garden, which is often referred to as the most important formal garden in town, forming a historically significant area. Olmsted integrated the property’s fields and woodlands with formal landscape elements like polo fields and gardens. Olmsted created a terraced axial walk that extended east from the house to an ice pond. The parterre garden is framed by evergreen trees, with a walkway leading to a circular fountain and statue. In the many years since, New Canaan has felt the pressure to redesign Waveny. Olmsted Brothers designed the garden for an estate, to be used by a single family and their guests. However, Waveny is no longer a private residence, but instead a public park enjoyed by many. New Canaan’s local Garden Club hopes to renovate and renew the parterre garden, making the design more inviting and open.

Olmsted Archives W. C. Bradley Estate (Columbus, GA)Located behind the Columbus Museum, the property was first owned by Brick Miller, a local lawyer who built a Mediterranean revival home on Wynn’s Hill in 1912 and hired William Marquis to create a personal garden along the hillside.Thirteen years later, industrialist W.C. Bradley had acquired the home. Wanting a larger garden to entertain family and friends, Bradley reached out to the original landscape architect, Marquis. By 1925, Marquis had joined Olmsted Brothers, and he returned to Georgia to adapt and finish his design. Bradley was very interested in the development of the garden, and frequently corresponded with Marquis, becoming heavily involved with the development. Together, their design exemplifies the more naturalistic gardens that were becoming popular in the 1920s, while also incorporating innovative technology into the surrounding landscape. Of the thirteen residential properties the Olmsted firm worked on in Georgia, the Bradley garden is widely recognized as the most significant and substantial of their designs in the state.

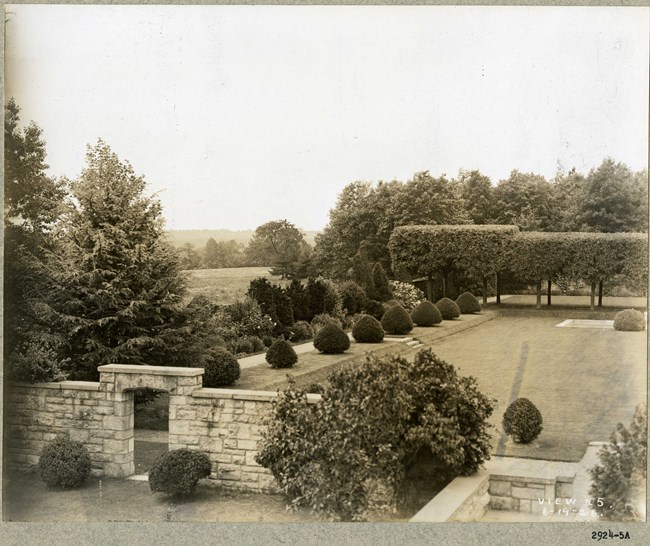

Olmsted Archives Oldfields (Indianapolis, IN)Located in a part of Indianapolis that during the early 1900s was reserved for highly exclusive, wealthy estates, Oldfields is the only one still left intact. Oldfields serves as one of the best surviving examples of a County Place Era estate in the U.S.Oldfields was built in 1912 for Hugh Landon, who was so impressed with the Olmsted Brothers’ garden design for Thomas Lamont’s Maine estate, he hired firm member Percival Gallagher to redesign the gardens. From 1920 to 1925, Gallagher designed a unified mix of formal and informal garden features. A wild garden in a deep ravine was planted with flowering trees, shrubs, and perennials, all along a rock lined river. What was once home to some of the most influential business leaders in Indianapolis, Oldfields is now part of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and is one of the most highly significant landscape designs in the area.

Olmsted Archives Moraine Farm (Beverly, MA)In 1880, Frederick Law Olmsted was commissioned to design over two hundred acres of depleted farmland for businessman John Charles Phillips. Instead of a well decorated country estate, Olmsted urged Phillips to use the surrounding landscape to his advantage, enhancing the natural beauty of nearby woodlands, meadows, and bodies of water.Collaborating with Peabody and Stearns, the Boston architects Phillips had chosen to build his mansion, Olmsted created a massive stone terrace overlooking Lake Wenham. In addition to lawns, hedges, rustic stone walls and a magnificent meadow, Olmsted integrated the latest advances in scientific farming and forest management. Just like in Back Bay, where Olmsted suggested the inclusion of Fens in the name, which described what the landscape was previously like, he left something in the name for Phillips. Olmsted suggested Moraine as the name for the estate, which in geology, is a ridge of glacial debris. Using the moraine as an elevated vantage, Olmsted created paths and carriage drives that looped through the seventy-five acres of forest, providing views of the lake and meadow.

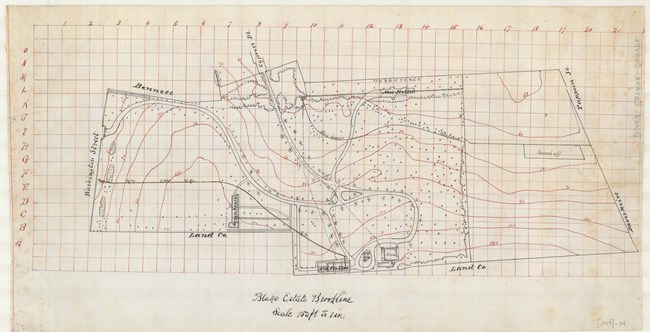

Olmsted Archives Blake Estate (Brookline, MA)Three years before Frederick Law Olmsted would make the move to Brookline, he was contacted by Boston banker Arthur Welland Blake to develop his family estate into lots for subdivision, roads included.Over a fifteen-year period, Olmsted and the firm would draw numerous plans for the Blakes property on Aspinwall Hill, however they were never executed. For a while the estate was an oddity: a large open tract of land in the heart of a rapidly developing community. It wasn’t until 1916 that the land was sold, roads and lots were divided, somewhat differently than what Olmsted had envisioned, and blended right in with the “streetcar suburb” just minutes from downtown Boston.

Olmsted Archives Wheatleigh (Lenox, MA)After Henry Harvey Cook purchased two hundred and fifty acres of land in Lenox, he hired Frederick Law Olmsted to design his estate like a pastoral park. Both Olmsted and Cook’s ancestors come from Britain, and both choose to honor that heritage, with Cook naming his estate after that homeland in Wheatley, England.Once again Olmsted would work on an estate with Peabody and Stearns, this time creating an Italian Renaissance mansion in the hills of the Berkshires, completed in 1894. The collaboration between Olmsted and Peabody and Stearns would be crucial in ensuring the home’s windows and balconies would provide sweeping views of open fields and Stockbridge Bowl. Olmsted used a circular drive to approach the home, ending in a formal court entrance surrounded by evergreen trees, and a marble fountain at the center. A patio terrace and formal garden is behind the house, which forms a U-shape. The terrace connects to open lawns, with walking paths lined with mountain laurel, azaleas, and rhododendrons.

Olmsted Archives Elm Court (Lenox, MA)In 1888, Emily Thorn Vanderbilt of the wealthy American family, and her husband William Douglas Sloane purchased ninety acres and spared no expense in creating their estate. Vanderbilt and Sloane hired the best architects, Peabody and Stearns, and the best landscape architects, FL. & J.C. Olmsted.Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. and John Charles Olmsted were given over forty acres to dedicate to lawn and formal gardens. The Olmsted design includes an ornamental pool framed by an arch covered in wisteria. Peabody and Stearns designed thirty-four greenhouses for Elm Court, where fruits and flowers would be raised for the estate. The Olmsteds designed a fountain to welcome those to the greenhouses. In 1908, after Olmsted Sr. 's death, another prominent landscape architect would make their way to Elm Court. Beatrix Jones Farrand placed herbaceous plants and roses on the grounds, as well an Elm tree, Olmsted’s favorite and where the estate got its name. Much like the Elm tree at Fairsted, this one also succumbed to disease in the early 1960s.

Olmsted Archives Elm Bank (Wellesley, MA)Olmsted Brothers were commissioned by William Hewson Baltzell and his wife Alice, who had just acquired two hundred acres of land after the death of Alice’s father, to design picturesque landscaping to be viewed from a large manor.Between 1914 and 1928, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and John Charles worked on the landscape at Elm Court. While their design included a tree-lined drive meandering through curves, the centerpiece of their design was the Italianate Garden. Elm Bank was occupied by families until the 1940s, when a religious organization bought the property to use for seminary housing and as a summer camp. It was used very briefly for this purpose, and after which it remained empty and neglected for over thirty years. Despite the neglect, the landscape elements designed by Olmsted Brothers still help historic significance, and in 1987, Elm Bank was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1999, Elm Bank became home to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, leasing thirty-six acres of land within Elm Bank. In the years since Olmsted Brothers’ work on the Italianate Garden, it has seen some deterioration. Like many Olmsted designs that meet this fate, restoration work is based on the original plans still stored at Olmsted NHS. To restore the Italianate Garden at Elm Bank, numbered plant lists and receipts from the original trees and flowers planted in the garden were reviewed.

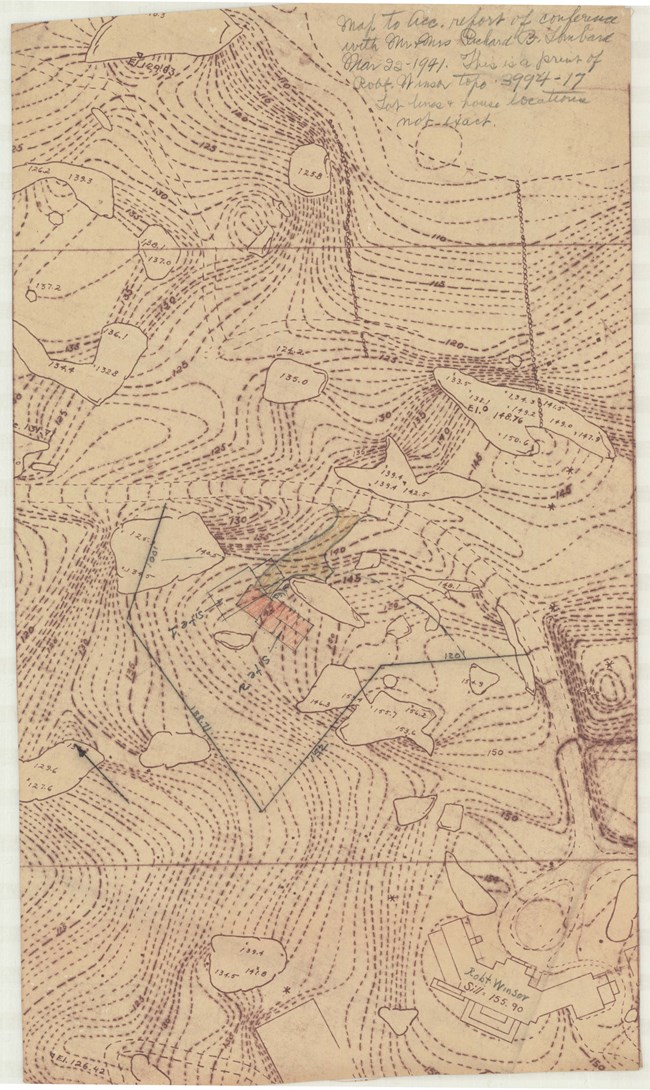

Olmsted Archives Chestnut Farm (Weston, MA)Chestnut Farm, the 472-acre estate of Robert Winsor, was once the second largest home in Weston. In 1883, Winsor purchased the land that would house his estate, and built a shingle style home on it. Between 1887 and 1890, Winsor acquired more property in the area.Beginning in 1910, Winsor began thinking of the possibilities of building a subdivision on his property. That year, Winsor hired Olmsted Brothers to make a general plan for his property. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. took the lead at Chestnut Farm, stating that Winsor “wants to keep place quiet and natural; but wants to build some woods-roads and gradually improve the place with the idea in mind of subdividing it as time goes on…into smaller places of (say) ten acres and upwards”. Winsor asked Olmsted to create a road system not only convenient for his personal use but would also be useful when the property was subdivided. Olmsted Brothers made sure to place those roadways based on topographical and geological features, taking advantage of the natural landscape. Olmsted Brothers also designed a four-acre pond at Chestnut Farm, with seventy-five workers arriving to the swampy site, removing unneeded land to make the pond deep enough for swimming. To this day, the pond left by the Olmsted's is used for skating in the winter.

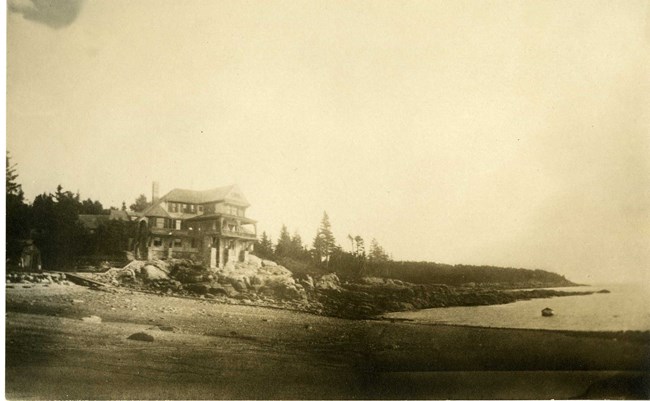

Olmsted Archives Pointe D'Acadie (Bar Harbor, ME)While George Washington Vanderbilt was acquiring the 146,000 acres of North Carolina land that would become his Biltmore Estate, he was in contact with Frederick Law Olmsted about a different project. In 1889, Olmsted began work landscaping Vanderbilt’s Bar Harbor estate.Named Pointe D’Acadie, Olmsted would include new roads, carefully composed tree plantings, a new stone terrace and stairs leading to the large, shingled home. Additionally, Olmsted dammed a small cove by the water that could be used as a naturalistic swimming pool, Bar Harbor’s first.

Olmsted Archives Felsted (Deer Isle, ME)After a prolific career designing green space across America, Frederick Law Olmsted’s health was deteriorating and his wife, Mary, decided to remove him from his bustling home-office in Brookline, and moved him to Deer Isle, Maine, in a bid to improve his failing health.Olmsted had already made a trip to England to combat his failing health but became depressed by the dreary English climate. It was Mary who asked her son Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to build the family a summer retirement home. In 1897, Olmsted Jr. contacted Boston architect William Ralph Emerson, known for his shingle style home designs in Maine, to build Felsted. Emerson’s landscape plan was intended to stimulate Olmsted Sr.’s decreasing mental abilities. The Olmsted’s spent one single summer at Felsted, at the end of which they were unhappy and Olmsted Sr.’s health continued to deteriorate. After Felsted, the family decided to commit Olmsted Sr. to McLean Hospital, where he would spend the rest of his life, passing away in 1903.

Olmsted Archives Florham Estate (Madison, NJ)A popular choice by the wealthy Vanderbilt family for the design of their estate, Frederick Law Olmsted was once again commissioned by the Vanderbilt family. This time, Olmsted would be working on the weekend estate of Florence Vanderbilt Twombly and her husband Hamilton McKay Twombly.Serving as landscape architect for Florham, a combination of the couple's first names, Olmsted designed Italianate gardens at the estate that still survives to this day. Completed in 1897, the couple didn’t just hire the best in landscape architecture, but also in architecture, with the home being designed by McKim, Mead, and White. Olmsted set the mansion on a hill that would overlook the Passaic Valley and Black Brook meadows. When giving his suggestions about the property to Twombly, Olmsted told him that “you have a sweep of landscape to an infinitely remote…obscure background…as much so as if you owned the state of New Jersey”.

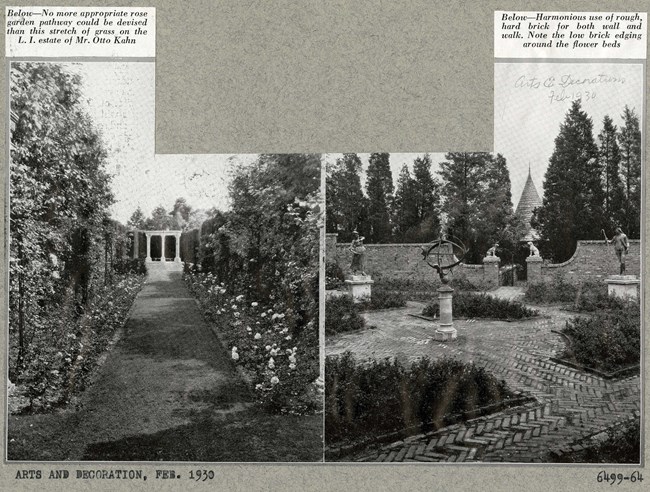

Olmsted Archives Oheka Castle (Cold Spring Harbor, NY)In 1916, financier and philanthropist Otto Hermann Kahn built his estate on a 443-acre plot of land that sat at the highest point on Long Island. Kahn would spend $11 million on his home, roughly $158 million if he were to build it today.After combining the first letters of his three names to get Oheka, Kahn hired Olmsted Brothers to design the grounds of the estate. The design centered on a formal sunken garden inspired by French landscape architecture. Olmsted Brothers’ garden included fountains, ten reflecting pools, statues, and tree lined paths. Additionally, Oheka housed one of the largest private greenhouse complexes in the country, tennis courts, an indoor swimming pool, as well as orchards and stables.

Olmsted Archives Planting Fields (Oyster Bay, NY)When William Coe needed the landscape of his estate designed, he reached out to Boston architect Guy Lowell and his partner Andrew Sargent, son of superintendent of Arnold Arboretum, Charles Sprague Sargent.When Sargent died in 1918, Coe immediately hired Olmsted Brothers to complete the design, which would happen over a ten-year period. Olmsted Brothers worked closely with the architects of the estate to create a proper setting for the house. They even transplanted two forty-foot copper beech trees from Coe’s wife’s childhood home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Olmsted Brothers created a series of charming vistas on the downhill slope of the property. Vistas were created by artfully scattering oaks around the property. Huge trees were already growing in abundance on the property, so Olmsted Brothers incorporated those into their design as well. Despite being the second landscape architects to work at Planting Fields, Olmsted Brothers had the longest lasting contribution, including key landscape features such as the greenhouses, Surprise Pool, Italian Garden, and the original entrance drive.

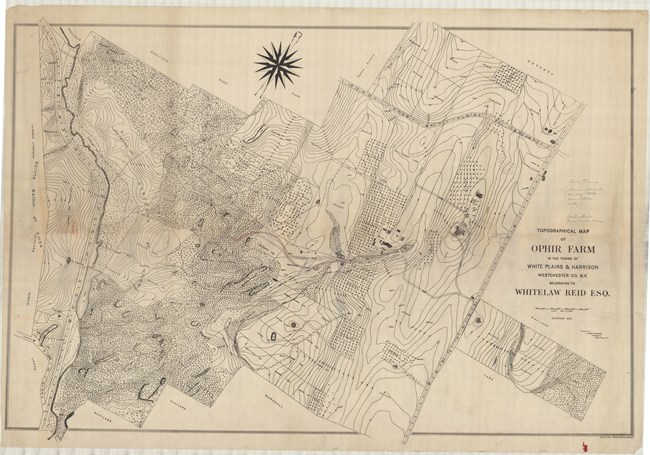

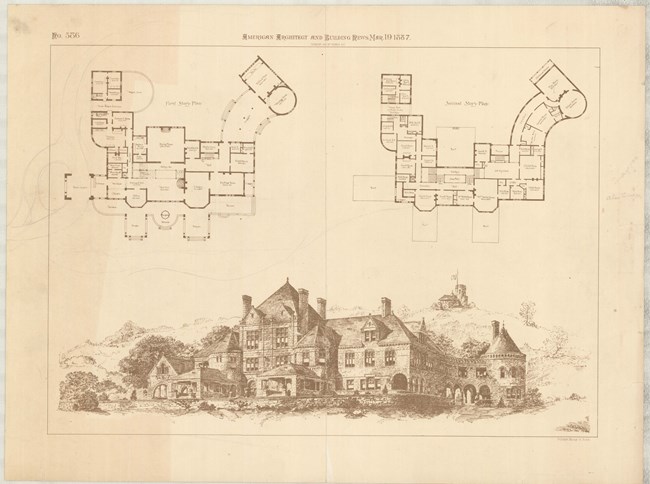

Olmsted Archives Ophir Farm (White Plains, NY)When Whitelaw Reid purchased Ophir Farm in 1887, he hired Frederick Law Olmsted to create plans not only for the landscape of the outdoor space, but as well as the architecture for farm buildings. Having spent some time running his own farm on Staten Island, Olmsted viewed himself as an experienced farmer, and was particularly interested in designing Ophir Farm.Olmsted’s time spent as a farmer shaped his approach to Ophir farm. Unfortunately, Olmsted had created such an elaborate design for the barns, that when the Reid’s opened their grand estate in 1892, the barns were still not completed. Reid had already acquired the professional help of architects McKim, Mead & White, who he wrote to at the end of 1892, stating that his “fear is that under the inspiration of Mr. Olmsted and with general tendencies of architects, he may be giving me a much finer thing than I want or rather much finer than I want to pay for”. Six years after Reid had asked Olmsted to choose a site and sketch plans for the farm building, construction of the barn began. Through 1895 the work proceeded without any delays, in part because Mead took over as chief architect when Olmsted fell ill. Today, remnants of Olmsted’s grand barn still exist.

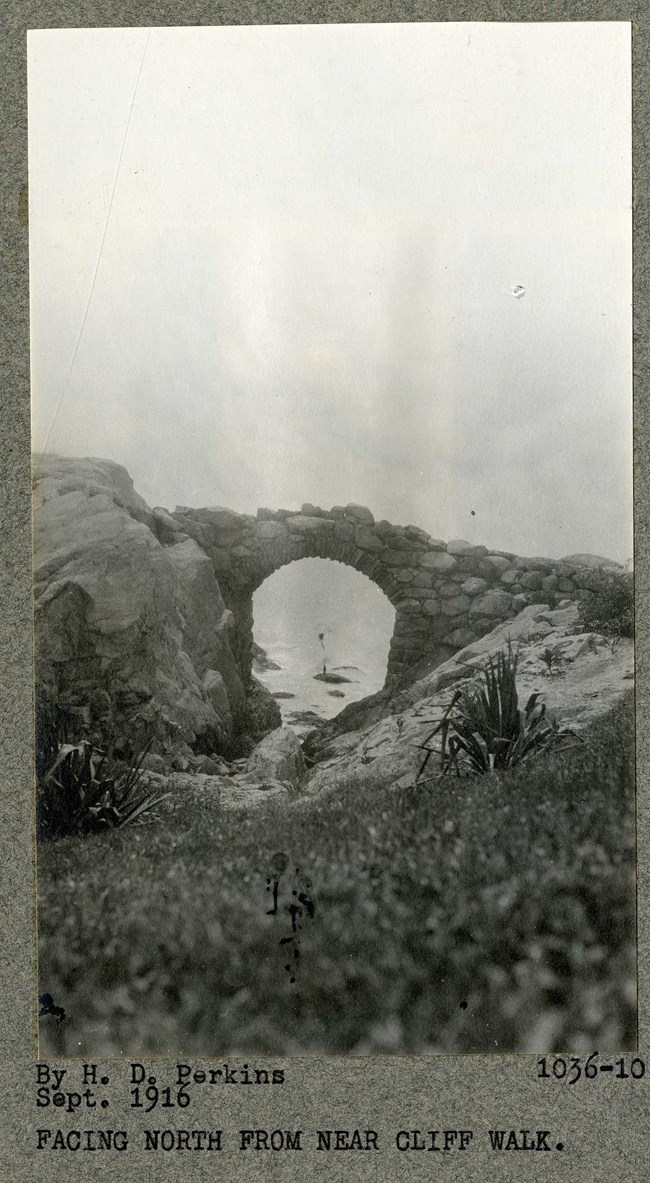

Olmsted Archives Rough Point (Newport, RI)Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1887 for the Vanderbilt family, the original design of Rough Point was meant to emphasize the connection of the property to the nearby ocean.When Olmsted completed Rough Point in 1891, the nearly eleven-acre property perched atop rugged cliffs featured views created through the layering of foliage and dramatic topography. Olmsted strategically placed trees to provide a sweeping expanse of lawn between the home and cliffs, and an arched stone bridge. While Olmsted’s arched bridge was damaged in a 1938 hurricane, it was restored to its original design. Whenever an Olmsted-designed landscape faces deterioration, the first step is often reaching out to Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site and asking to view any files related to the project. This way, no new plan needs to be created, instead you use the original one.

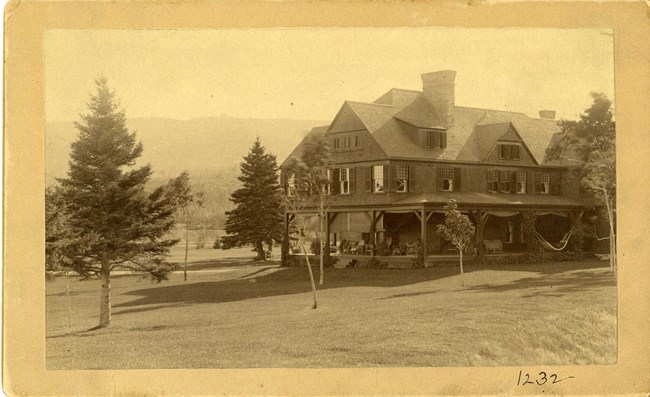

Olmsted Archives Shelburne Farms (Burlington, VT)During his three years at Shelburne Farms, Frederick Law Olmsted organized the property into three distinct areas: farm, forest, and park. Olmsted additionally developed a winding road system to highlight the rolling lakeside topography and views.Within a month of his first visit in 1886, Olmsted had formulated a basis for his proposal, which he described to Charles Eliot as “a perfectly simple park, or pasture-field, a mile long on the lake, half a mile deep, the house looking down over it”. Olmsted was convinced that once Shelburne Farms was completed, it “would be the most interesting and publicly valuable private work of the time on the American continent”. One proposal that Olmsted ardently promoted was that the estate include an arboretum of all the trees and shrubs native to Vermont. A great deal of planting was done according to Olmsted’s recommendation, but the arboretum was never completed. This was a huge frustration for Olmsted, because while Shelburne Farm was privately owned, he believed it should have a public purpose. With no arboretum in sight, Olmsted began losing enthusiasm for Shelburne Farm. At the end of the summer of 1888, Olmsted handed over work at Shelburne to his sons and associates. Despite leaving, Olmsted helped create an estate which offers some of the most pleasant views of Vermont’s pastoral landscape and dramatic views of the Adirondack Mountains.

Olmsted Archives Thornewood Castle (American Lake, WA)Olmsted Brothers designed many of Seattle’s original parks over a hundred years ago, with John Charles Olmsted taking a leadership role in the designs out in the Pacific Northwest. At Thornewood, the crowning achievement was a sunken English Garden, also referred to as The Secret Garden.The walled garden is entered through wood gates over a hundred years old, with a walkway bordered by flowers and shrubs circling the entire garden. Olmsted planted wisteria, purple clematis, climbing hydrangea, and pillar roses in The Secret Garden. Steps in the front and rear of the garden lead visitors down to a sunken area, where the central focus is a tranquil fountain surrounded by a lush lawn. The Secret Garden is where many of Thornewood’s statues are found. In 1926, The Secret Garden was named one of the five most beautiful gardens in America, and again in 1930, this time by the Garden Club of America. Olmsted surrounded the house with spacious gardens and lawns and, despite being designed over one hundred years ago, much of his design remains intact today.

Olmsted Archives Eugene D. Nims Estate (Woods Hole, MA)In 1929, Eugene D. Nims contacted Olmsted Brothers to do extensive landscape planning on his estate in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Nims wanted his property divided into lots, and bridle paths created through surrounding shrubs. Nims also wanted his vegetable garden moved closer to his house, integrating the steep eastern bluff, the house, and the surrounding land.From Olmsted Brothers, L.H. Zack was tasked with beginning the survey of the property and taking photographs, used by firm members who couldn’t travel to the site. As requested, the plan divided the property into six lots, with a second driveway added to access neighboring lots. Zack also used topographical maps to decide where bridlepaths were to be done. Zack also suggested that one path go along the edge of a nearby pond, just below the house to the East. Over time the paths were cut, though it is unknown if the edge of the pond was as densely packed with vegetation as Zack suggested. Except for the minimal staking of the paths, nothing of Olmsted Brothers’ plan was executed.

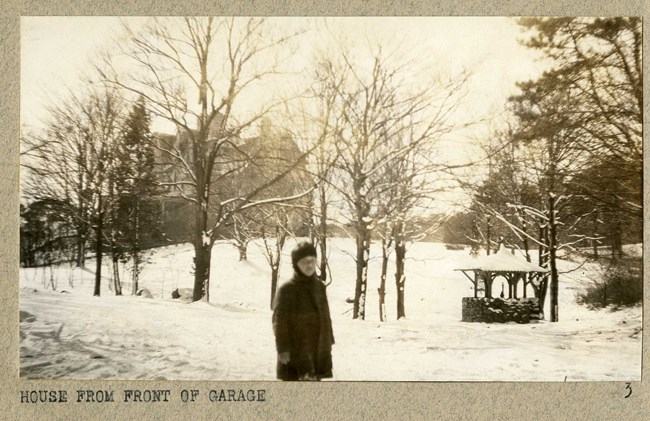

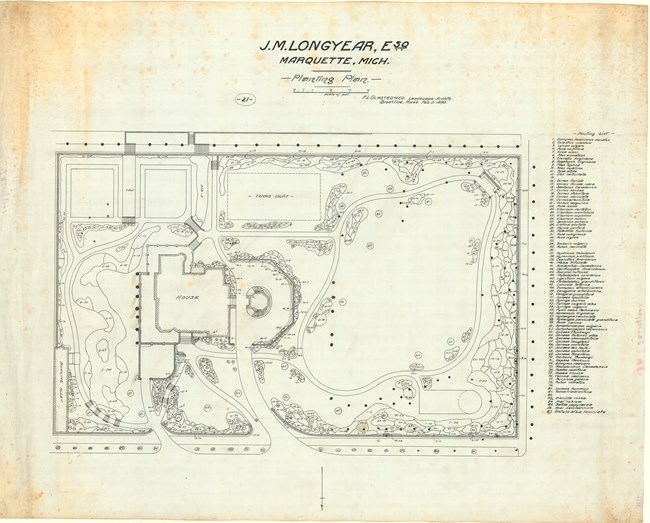

Olmsted Archives J.M. Longyear Estate (Marquette, MI)In the Summer of 1890, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired to design the grounds of the Chicago World’s Fair. One year later in July, Marquette, Michigan resident John Longyear wrote to Olmsted, asking him to come to Marquette at his earliest convenience to create plans for his estate.Longyear was anxious to have the grounds landscaped. After his first visit in 1891, Olmsted agreed the following year to create a model of the plantings he envisioned at the estate. The uneven terrain of the area presented a challenge for Olmsted, which he chose to fix by covering the grounds with creeping plants, shrubs, and vines. Olmsted wrote that “We believe that in general it is not advisable to keep such steep banks in turf, as it is very difficult to mow…and almost impossible to keep the turf in perfect condition…”, though with bushes, vines and trees, the area would be more picturesque and interesting. With the Chicago World’s Fair occupying much of his time, Olmsted sent firm member Warren Manning to supervise plantings at the site. To begin, Olmsted believed that the three acres to be planted should first be dug up and prepared with muck and stable manure. Unfortunately, the severe winter climate presented a challenge to the plantings. After the first Winter, Longyear wrote Olmsted reporting that some plants had not survived the cold months. Olmsted and Manning recommended replanting some of the area with wild roses and huckleberries. In 1897, Longyear and Olmsted began wrapping up their correspondences, with suggestions to expand the gardens to include tulips, crocuses, daffodils, and many species of fruit trees.

Olmsted Archives Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Gardens (Long Beach, CA)Now known as the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Gardens, the area started as Susanna Bixby Bryant’s 1927 garden on her Orange County estate. A fan of nature, she wanted to explore and demonstrate the value of California native plants and wildflowers. Two years after planting her garden, she would hire Olmsted Brothers to help design the rest of her 200-acre property.A 1930 plan shows proposed plantings, pools, and pathways, with original trails and roads laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr, who also made several detailed studies on landscaping. After Bryant’s death, the collection was relocated to Claremont College, and is now known as the California Botanic Garden.

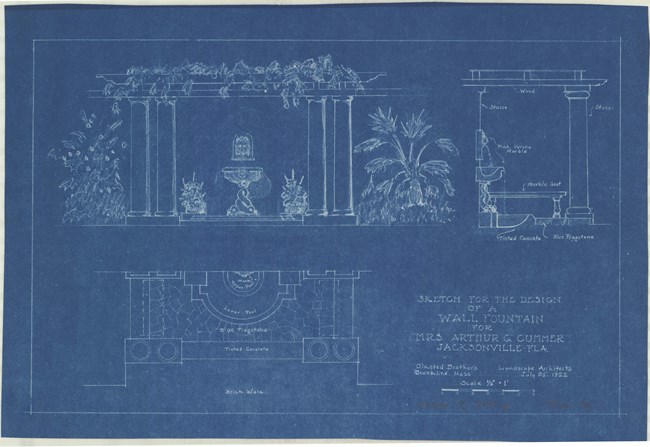

Olmsted Archives Mrs. Arthur G. Cummer Estate (Jacksonville, FL)In 1931, Olmsted Brothers were hired by Waldo and Clara Cummer to redesign their property, which was adjacent to Waldo’s brother and sister-in-law’s estate. Olmsted Brothers were tasked with incorporating a new plot of land, which had been acquired after the death of Waldo’s mother, Ada.Firm member William Lyman Phillips led the design, using a varied palette of materials to bring together trees and plants most appropriate to the Florida site. While much of Olmsted Brothers’ work was destroyed during construction projects, a significant riverfront area, known as the Olmsted Garden, remains. That existing fragment was acquired by the Museum in 1992, and in 2013 restoration work was undergone, using the original Olmsted plans.

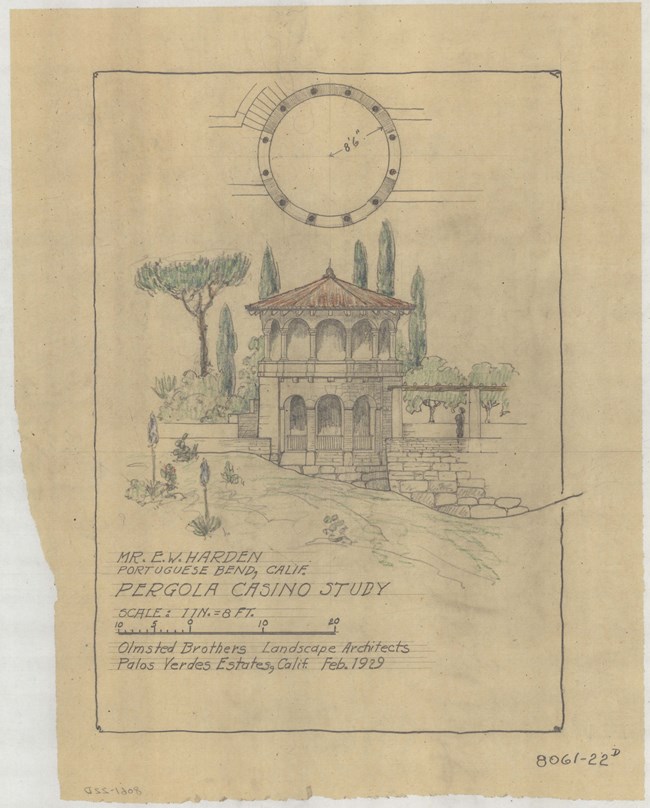

Olmsted Archives E.W. Harden Estate (Palos Verdes, CA)In 1925, the Hardens of Palos Verdes hired Olmsted Brothers to direct “a large amount of plantings” at their estate overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was already deeply involved in the planning of Palos Verdes, so much so that he moved there with his family. Olmsted Jr would create “a pergola, summer houses and walks around the beautiful quarter-mile stretch of the small bay between Portuguese Point and Inspiration Point." For the Harden Family.

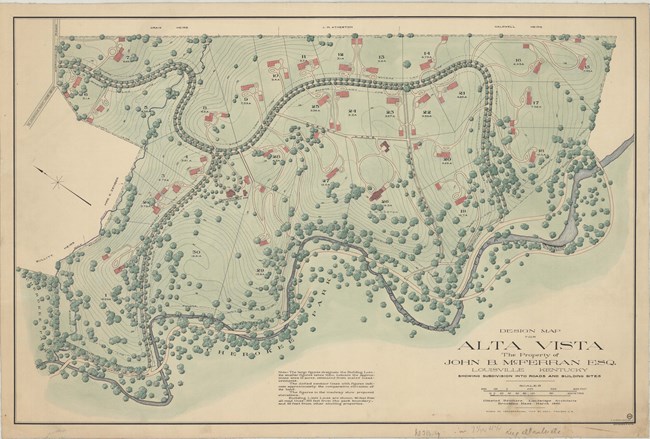

Olmsted Archives Alta Vista (Louisville, KY)Many subdivisions the Olmsted firm worked on often start as private estates, with a wealthy landowner wanting to profit off their estate. That is the case with Louisville’s Alta Vista, which began as John B. McFerran’s private estate. Olmsted Brothers were hired in 1900 to prepare a subdivision on McFerran’s trotting farm above Bear Grass Creek near Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.’s Cherokee Park.Today, principal roadways Olmsted Brother laid out, like Maple Road and Alta Vista Road, retain their form, with the exception of a straightened portion of Alta Vista Road, caused by Interstate 64 cutting through part of the property. From McFerren’s time, only Garden Court, also designed by Olmsted Brothers, remains within the subdivision.

Olmsted Archives Garden Court (Louisville, KY)In 1906, John Charles Olmsted travelled to Louisville, Kentucky to visit Mrs. Caldwell and Misses Norton to discuss a planting plan for their estate, known as Garden Court. John Charles advised the women on the size of their stable, writing that "they ought not to cut down on the number of stalls, as this is a permanent investment while automobiling may be a temporary fad."Automobiles did not end up being a fad, but thankfully Garden Court lies within the Alta Vista subdivision, which Olmsted Brothers designed with many tree-lined, curving roads. Olmsted Brothers would also work on Misses Norton’s property in Hendersonville, North Carolina.

Olmsted Archives E.W. Gurney Estate (Beverly, MA)From 1881 to 1884, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. and John Charles Olmsted designed the private estate of Ephraim W Gurney in Beverly, Massachusetts. Due to Gurney’s unexpected death, the project was never finished, though the property still reflects features of Olmsted’s original plan. The most significant feature left over is the retaining wall, which separated the house from the nearby steep hillside. This was a necessary addition to help protect the wilderness of the estate and strengthen the planting plan.

Olmsted Archives Brandegee (Brookline, MA)A couple of miles from the Olmsted Office is Brandegee Estate, the estate of Charles Sprague, not to be confused with Charles Sprague Sargent who worked on Arnold Arboretum with Frederick Law Olmsted. Sprague hired Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot to work on the initial planning for the grounds, with special attention to the garden.Partner Charles Eliot led the project, however tension between Eliot and Sprague led to the firm’s dismissal. Charles Platt, a frequent collaborator with the Olmsted firm whose brother William had apprenticed with Olmsted, was chosen to finalize the design. Pratt added a formal Italianate Garden, which today, with the estate, is largely intact.

Olmsted Archives Kragsyde (Manchester-By-The-Sea, MA)In the early 1880s, Frederick Law Olmsted worked on George Nixon Black Jr.’s imposing Manchester-by-the-Sea estate. Working closely with the architectural firm of Peabody & Stearns, Olmsted chose to orient the house, nestled at the top of a rocky bluff overlooking Massachusetts Bay, to maximize coastal views. An 1882 plan shows the inclusion of a carriage house, stable, laundry yard and house yard.The most fascinating feature of the estate, known as Kragsyde, was the archway that was built into the side of the house, allowing for passage and visibility to either end of the property. Olmsted designed the surrounding landscape to fit into the natural scenery, with low shrubs and native trees to compliment the house.

Olmsted Archives W.C. Loring Estate (Prides Crossing, MA)Beginning in 1888, Frederick Law Olmsted planned the Massachusetts estate of William C. Loring. Due to the rugged landscape of the chosen site, intensive grading and planting work was required, with Olmsted calling for grounds to be manipulated to create steep slopes. Before Olmsted could design, he required the grounds to be cleared, damaged trees removed, and soil to be stripped. Olmsted designed a 1500-foot driveway to lead up to the house from the main road.

Olmsted Archives Fairsted (Brookline, MA)Prior to his move to Brookline, whenever Frederick Law Olmsted had work in the Greater Boston area, he would spend the night at Henry Hobson Richardson’s Brookline home. One snowy morning at Richardson’s, Olmsted wakes up, looks outside, and sees the plows already at work removing the snow. He declares “this is a civilized community. I am going to live here.”Olmsted would purchase the foursquare style home from the Clark sisters, though neither sister wanted to leave so the two families struck an agreement. The Clark’s sold their home and 1.75 acres of land, and in return, John Charles Olmsted built them a home, free of charge, overlooking Fairsted, where they would live rent for the remainder of their lives. A large open lawn, known as the South Lawn, provides a point of contrast to the dense planting along the perimeter, which bordered Isabella Stewart Gardner’s summer estate. Vines were meant to dominate the façade of the house, creating a sense of wilderness. Today, any groundwork done at Fairsted references historic images and plans, to keep the landscape as close to original as possible.

Olmsted Archives Sheep Pasture (North Easton, MA)The Ames family would commission the Olmsted Firm several times to design for them, from the Oliver Ames Library to the North Easton Town Complex. In 1891, Oliver Ames II hired Frederick Law Olmsted to design his estate. Due to its location on a meadow plateau, Ames named his estate Sheep Pasture, which was dominated with large boulders.The mansion was approached by a horseshoe-shaped driveway, with densely planted trees to hide the house from the street. Olmsted drew inspiration from his previous work at Waltham’s Stonehurst and chose to decorate the back of the house with a rock-faced terrace. Olmsted’s 1892 planting plan shows an intent to plant over one hundred species of trees and shrubs all around the property, except for the southern lawn, which was intentionally left open.

Olmsted Archives Stonehurst (Waltham, MA)One of many collaborations between Frederick Law Olmsted and Henry Hobson Richardson, both men designed the Robert Treat Paine estate with the intent of creating a mountainous summer escape. Like other Olmsted designed estates of the time, the 109-acre property featured a long winding approach from the road to the home.The grounds were designed to complement the existing scenery, and Olmsted even instructed Paine on how to care for the estate. In 1886, John Charles Olmsted wrote to Paine about transplanting trees from nurseries in the Western United States to the Waltham property. Olmsted’s first apprentice, Charles Eliot, who was related to Paine, made improvements to the entry drive. |

Last updated: June 20, 2024