|

No aspect of the Olmsted firm’s work is more important- and more often overlooked- than its contribution to the history of city and regional planning in the United States. Landscape architecture, as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux first defined the term, was itself a new form of American urbanism. As Lewis Mumford wrote in 1931, “By 1870, less than twenty years after the notion of a public landscape park has been introduced in this country, Olmsted had imaginatively grasped and defined all the related elements in a full park programmed and a comprehensive city development.” By the 1880s, as the Boston park system was taking shape, the apprentice Charles Eliot was already responding to Olmsted’s suggestions of how park planning could extend to the regional scale. Regional planning in the United States subsequently developed from its roots in regional park plans (such as Eliot’s metropolitan Boston parks) just as city planning had origins in municipal park design. City and regional planning demanded legal expertise, statistical analysis, and other skills unfamiliar to traditional landscape designers. By the early twentieth century landscape architects were expected to collaborate with engineers, architects, lawyers, and others to devise a range of regulatory and design solutions to the problems of urban growth. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago was an influential example of the multidisciplinary collaboration, as was the 1901 effort to replan Washington, D.C., for which Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. assumed his father’s role. Between 1907 and 1917, a new profession was born as more than one hundred American towns and cities established comprehensive city plans. A full partner in the firm since 1897, Olmsted Jr. was a leading practitioner and, as historian Susan L. Klaus notes, the “chief spokesman of the planning movement during its formative years.” In 1910, for example, he was working with the architect Cass Gilbert on a plan for the city of New Haven that utilized extensive data on demographics, tax rolls and industrial trends. The next year he published similar survey of Pittsburgh and Rochester that also assembled unprecedented statistical information for those cities. In 1909 the Harvard School of Landscape Architecture (begun under Olmsted Jr. in 1900) offered the country’s first professional instruction in “City Planning,” and in 1917 Olmsted Jr. and the lawyer Flavel Shurtleff founded what became the American Institute of Planners. By the 1920s city planning necessarily expanded to address entire metropolitan regions, a development presaged by the Olmsted firm’s work not only in Boston, but also for clients such as Essex Country, New Jersey, beginning in 1898. The first county park system in the country, this regional park plan integrated municipal and county parks and parkways. Olmsted associates of the period, especially Warren Manning, continued and expanded the regional planning ideas of the Olmsted firm, and so the full significant of the firm’s city and regional practice is not to be found in this Master List alone. Many of the regional and even national park planning project of the New Deal of the 1930s, for example, were the fruition of ideas that traced their origins back to the Olmsted firm office in Brookline, Massachusetts. It was especially appropriate, then, that Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Resources Planning Board, which oversaw federal park and resource planning, had as its executive the landscape architect Charles W. Eliot II, Charles Eliot’s nephew. Text taken from The Master List, written by Ethan Carr Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

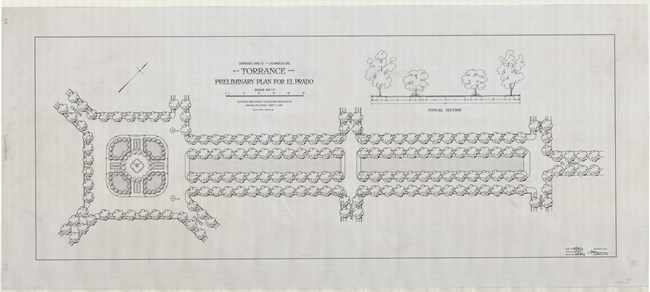

Olmsted Archives Dominguez Estate Company (Torrance, CA)In 1826, Manuel Dominguez built his estate on 75,000 acres of land gifted to his uncle from the King of Spain, as a thank you for his military service. By the late 1800s, massive tracts of land were being gradually sold off. In 1911, real estate developer Jared Sydney Torrance purchased over three thousand acres to carve out the city of his namesake.Torrance hired Olmsted Brothers to design his new South Bay community in 1911, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. taking lead on this project. Olmsted Jr. was known for integrating structures into a landscape, never wanting those structures to dominate a landscape, instead perfectly fitting in. The open green expanse of the tree lined El Prado was laid out at an angle, leading a spectator’s eyes towards the towering mountains in the distance. El Prado reflects Olmsted Jr.’s deliberate attempt to work green space and natural beauty into his urban designs. Olmsted’s plan for Torrance was creative, dividing the town into three distinct districts: the business district at the city’s core (now known as Old Torrance), the industrial district to the North and East of the city’s core, and the residential district to the West. Olmsted Jr. chose modern architect Irving J. Gill to design Torrance’s original buildings, including the city’s railroad bridge. Olmsted Brothers likely suggested Gill as architect because they had already worked together on the Panama-California Exposition. As is often the case with Olmsted designed landscapes, the plan for Torrance came out of a different plan, one for a park on the other side of the country. The 1906 plan for Forest Hills Garden in New York is based on the garden city principles, that humans should live in harmony with nature. The Forest Hills plan included streets radiating out from a railway station, which would form the basis for Olmsted Jr.’s Torrance plan.

Olmsted Archives Birmingham City Plan (Birmingham, AL)In the summer of 1924, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. began to write his report on a park system for Birmingham, Alabama, assisted by the future project manager of the site, firm member Edward Whiting. Published a year later, the report called for parks within easy walking distance for all residents, regardless of socio-economic or racial group, that would serve both active and passive recreation.From his father, Olmsted Jr. learned how important parks were to the spiritual refreshment and physical welfare of stressed city dwellers. Prior to Olmsted Brothers involvement at Birmingham, the city had only 600 acres of park to serve 200,000 citizens, a wholly inadequate number. Olmsted Brothers’ report recommended the creation of beauty spots and athletic fields, and the reservation of vast lands in undeveloped areas critical for the protection of the area’s domestic water supply. The plan also included building parkways along ridge tops to offer the community impressive outlooks, as well as offering recreational amenities for the thriving industrial center Birmingham had become. Wanting immediate park improvements, from 1924 to 1926, Olmsted Brothers would design plans for three parks as well as reviewing plans for others. At the core of Olmsted Brothers philosophy in Birmingham was a resource-based plan that would be carefully coordinated with engineers in order to lay out beautiful and usable open spaces.

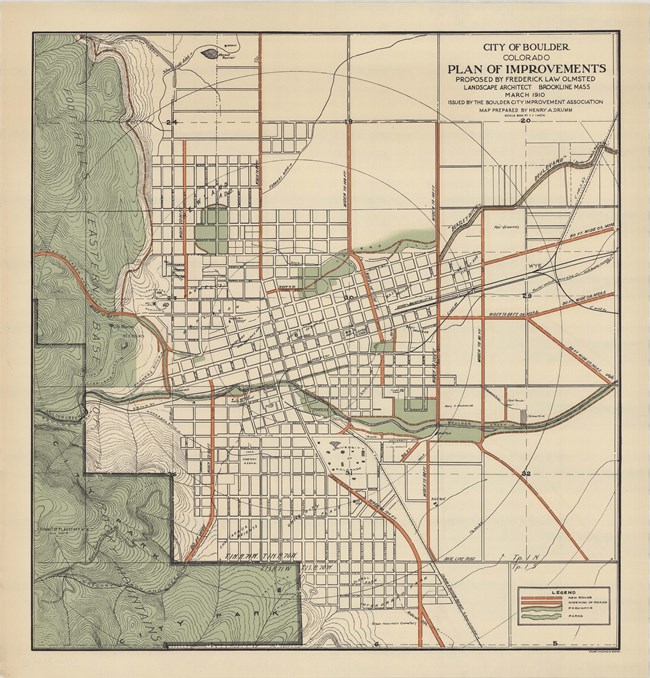

Olmsted Archives Boulder, Colorado Improvement Association (Boulder, CO)In 1903, a group of philanthropic citizens joined forces to promote “the improvement of Boulder in health, growth, cleanliness, prosperity and attractiveness.” The group they formed was known as the Boulder City Improvement Association (BCIA) and four years after their founding, they sought the services of Olmsted Brothers.Writing to Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., the BCIA wrote that “we are a small but ambitious little town…situated 30 miles northeast of Denver. We want advice, and the best obtainable, as to how to improve our city as to Parks, Boulevards and general plans for Civic betterment.” Olmsted Brothers’ first prepared report for the city, The Improvement of Boulder, Colorado, came out November 1908, six months after Olmsted Jr. had made a brief visit to the area. The BCIA received thirty pages of dense text including an illustrated map. The report covered details like street trees and light, as well as the broad idea of limiting manufacturing in the city and the use of fine homes. Besides work on the landscape, Olmsted Jr. also addressed the progressive era themes of a good government, the appropriate use of police power, and taxation to support the development of infrastructure. Olmsted Brothers’ plan also included planting plans for public schools, work on sewers and drainage systems, and a grand scheme for park improvements that would stretch over eighty city blocks, with work continuing into the 1920s.

Olmsted Archives New Haven (New Haven, CT)Preparing to expand their growing city, New Haven leaders reached out to Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to request his expertise in creating a comprehensive plan for the city, which he submitted in 1910. The 138-page document described an ambitious plan to construct wide boulevards and a new public plaza.In the opening paragraphs of the report, Olmsted Jr. described how he would transform New Haven from a “pleasant little New England college town” to a “widespread urban metropolis of the 20th century.” Olmsted Jr. called for more small parks for local purposes and warned against crowded tenements, which would result in filthy, ignorant people. In 1913, the City Plan Commission was established, and the next year, Olmsted Jr. was asked to provide landscape designs for the city, this time for the town Green, where he planned to plant double rows of elm trees. “A generous open space is needed” in New Haven, where visitors will have their first impression. The result is a benchmark of American urban planning and a perfect example of what a new city would look like in the 20th century.

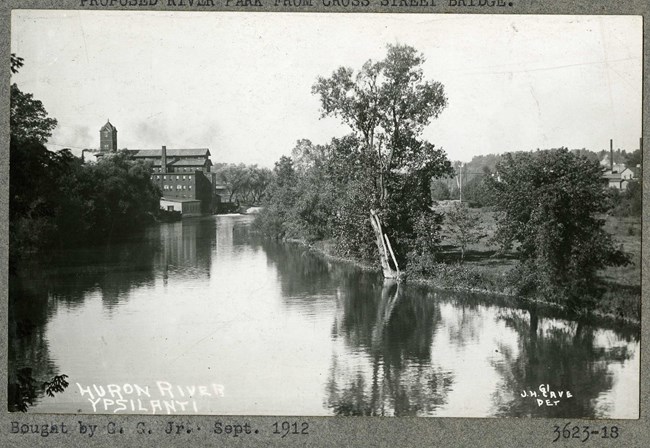

Olmsted Archives Ypsilanti City Report (Ypsilanti, MI)In 1913, Olmsted Brothers were commissioned by Ypsilanti to provide advice on how to help the town grow, not only to attract business and industry, but also to provide a healthy living environment for its citizens. Focusing attention on the Huron River, Olmsted Brothers were blunt in their criticism of the area.In their report, Olmsted Brothers noted that “Huron River with its large natural reservoirs and its steep channel, was long ago claimed for economic uses, by water power development in a small unsystematic way. Many mills were built but most of them have since fallen into disuse and decay, and the river is now largely in a picturesque state of neglect. Its shores now overgrown in many places”. While hired to landscape Ypsilanti for its then six thousand residents, they were also able to design the area's parks as well. Olmsted Brothers called for green space along the river, a park entrance off of Michigan Avenue, and pathways along the perimeter of green space, all of which was implemented.

Olmsted Archives Kohler, WI (Kohler, WI)After industrialist Walter Kohler Sr. traveled through Europe, he was inspired to pursue the development of a substantial garden city adjacent to his factory. After already designing the grounds of his nearby estate, Riverbend, Kohler hired Olmsted Brothers to design the town’s expansion in the mid-1902s.Olmsted Brothers also proposed plazas anchored by businesses and civic institutions at meeting of streets, as well as curved drives in the residential portion of the town. Many of Olmsted Brothers' more ambitious plans for Kohler went unrealized due to the Great Depression.

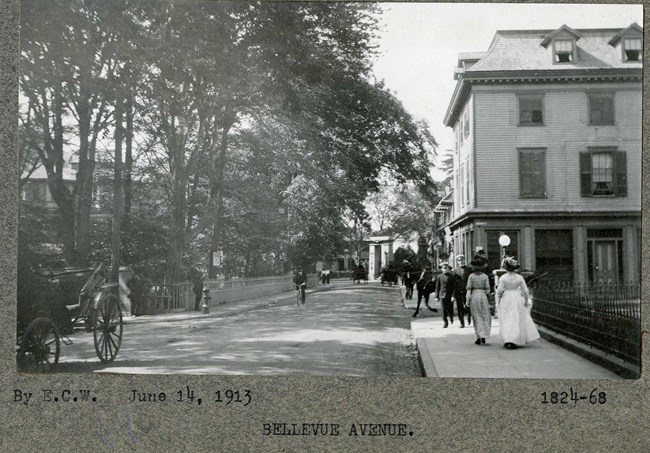

Olmsted Archives Newport Improvement Association (Newport, RI)In August of 1913, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. submitted his report, Proposed Improvements to Newport, to the Newport Improvement Association. Thankfully, Olmsted Jr didn’t go into this project entirely alone, for he was able to build on the significant planning previously started by his father and brother.While the firm of F.L. and J.C. Olmsted had already shaped the grounds for some of Newport’s wealthiest residents in the early 1880s, their most important projects in the area were development conglomerates, using large swaths of land for residential enclaves. Olmsted Jr.’s design and plan for Newport was to enhance the existing setting and characteristics of the area. By emphasizing the natural assets of the area, and the borrowed views that are shaped by its topography, Olmsted Jr. was able to push for targeted designs for several other areas of Newport. Additionally, Olmsted Jr. felt the need to safeguard scenery found throughout the city, so he recommended building codes and street improvements that wouldn’t alter his design.

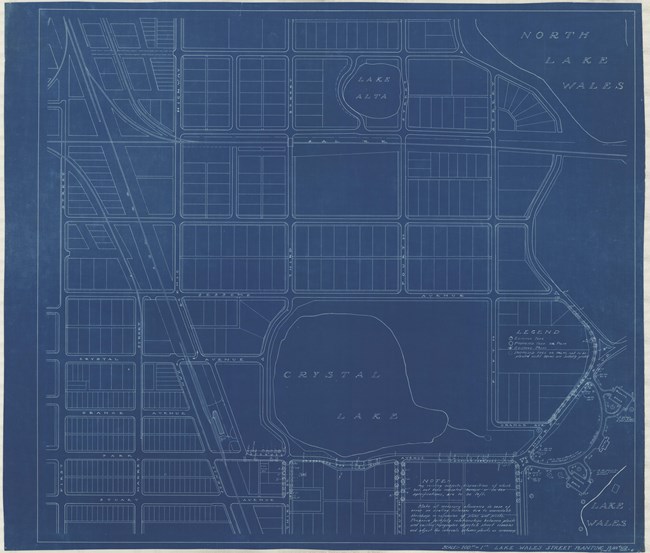

Olmsted Archives Lake Wales City Plan (Lake Wales, FL)While working on Central Florida’s Bok Tower Gardens in the 1920s, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. completed a comprehensive plan for neighboring Lake Wales, with the hope of creating a “city in a garden” with streets lined with rows of palms and understory trees. Olmsted Jr. submitted his plan for Lake Wales in 1931, drawing on Great Britain’s garden city movement of the late 1880s.A network of trails traverses Lake Wales, linking people to parks and establishments, making Lake Wales the first city in Florida to have a comprehensive master plan designed by any iteration of the Olmsted Firm. Additionally, Olmsted Jr. created the original zoning codes for Lake Wales, and while the planting plan was never completed, the city is a unique, southern example of his prolific work.

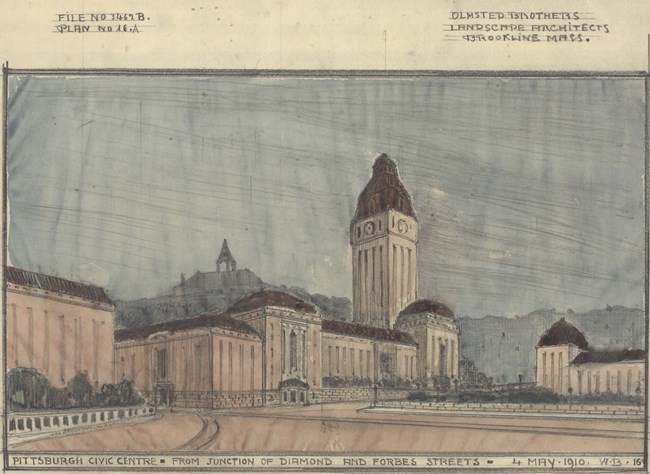

Olmsted Archives Pittsburgh Civic Commission (Pittsbugh, PA)Olmsted Brothers were contacted in 1898 by Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Works, who requested assistance in planning the city’s growing park system. By 1910, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr had begun preparing a report titled “City Planning for Pittsburgh Outline and Procedure”, with assistance from a team of engineers.Olmsted Jr.’s report focused on the development and planning of Pittsburgh’s Civic Center, addressing topics like water transportation, public lands, public buildings, sewage systems and legislative problems. Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Works must have been impressed by Olmsted Jr.’s report, as it was adopted a year later.

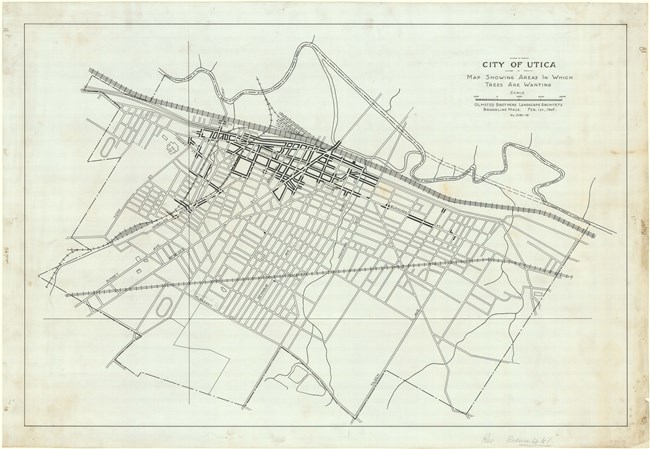

Olmsted Archives Utica City Improvement (Utica, NY)With the support of the local community, Olmsted Brothers were able to play a significant role in the development of Utica, New York’s park system and city planning. Hired in 1908, Olmsted Brothers transformed the town’s farmland into 600-acres of parks, parkways, gardens, and city landscape. That year, Olmsted Brothers published their ‘Report of the Committee on Beautifying Utica of the Utica Chamber of Commerce”.In order to make space for both transportation and street planning, Olmsted Brothers recommended placing tracks underground to better manage traffic. Also in their report, Olmsted Brothers proposed ““an attractive parkway with electric car service on a private right-of-way running direct to Baggs’ Square and short circuiting, so to speak, the whole of North Genesee Street.”

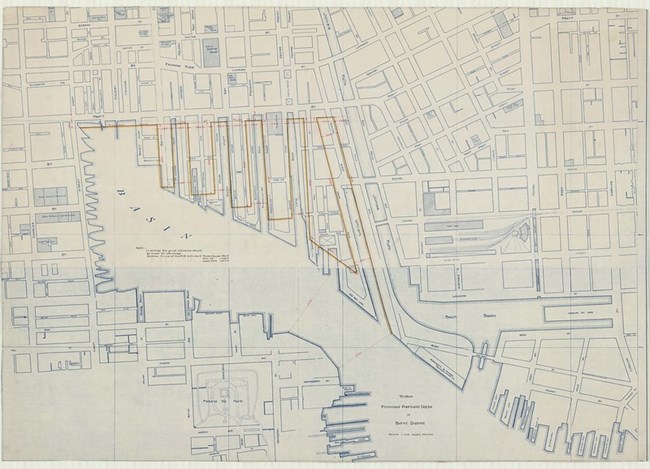

Olmsted Archives Baltimore Fire, 1904 (Baltimore, MD)In 1902, Baltimore, Maryland’s Municipal Art Society joined with the city’s Park Board, to commission Olmsted Brothers to plan a municipal park system for the area. Olmsted Brothers, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. taking lead, recommended creating three parkways. Despite enthusiasm from both city leaders and the public, the park system was slow to develop.Olmsted Jr. was overseeing the plan with colleagues P.R. Jones and Percival Gallagher, all of whom worked with the city’s superintendent of parks. Work continued until 1904 when a fire destroyed much of downtown Baltimore, delaying work for two years. On February 18th of that year, ten days after the fire ended, Olmsted Jr. conducted a five-day study outlining recommendations for the post-fire rebuild. In addition to physical improvements, Olmsted Jr. also wanted to use this opportunity to work with architects, creating harmonious streetscapes. Most of Olmsted Jr.’s recommendations involved widening the streets. Budget cuts and rapid urban growth would present challenges to the original plan, not all of which were completed.

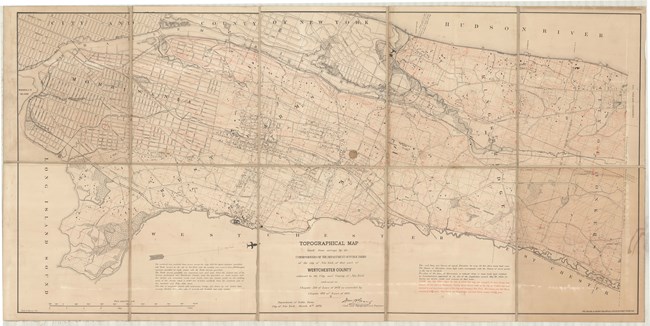

Olmsted Archives Westchester County (Westchester County, NY)In 1875, Frederick Law Olmsted was commissioned by the New York City Department of Parks to draw plans for a section of the Bronx, known as the 23rd and 24th Wards. Included in the Wards were “the larger part of the great promontory, the shank of which is crossed by the line dividing Yonkers from New York, and which terminates three miles to the southward in the abrupt headland of Spuyten Duyvil.”Working with engineer James R. Croes, Olmsted helped design several areas within the Bronx section of Westchester County. Together, the pair faced challenges due to the area’s rugged surface, “broken by ledges, and…numerous steep declines on its hillside.” In many of the residential communities in Westchester County, winding and curving roads became key features. |

Last updated: June 26, 2024