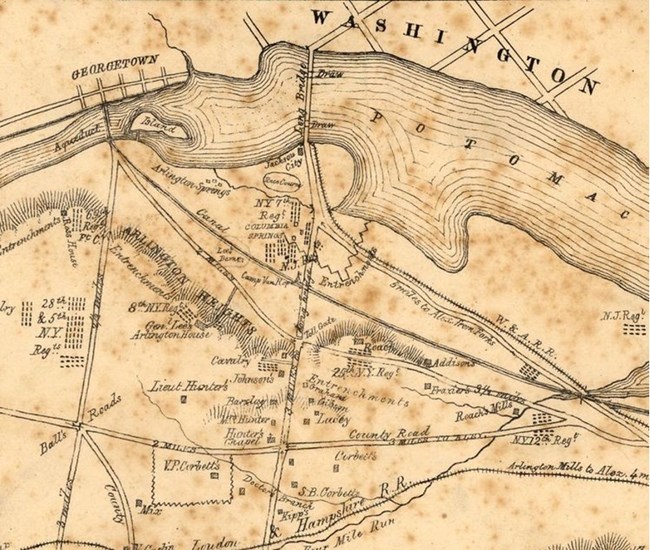

Library of Congress When Robert E. Lee resigned his commission in the U.S. Army and cast his lot with the Confederacy, he realized his decision would likely bring the war directly to his front door. The same sweeping views of Washington, D.C. that made Arlington House such a notable landmark also made it an immediate strategic concern for both the north and south. Arlington House was less than three miles away from the White House – within the range of a rifled cannon. In a cabinet meeting on April 20, Secretary of State William Seward informed President Abraham Lincoln that if the Confederates placed an artillery battery atop Arlington Heights, Lincoln and his cabinet, “would not know at what moment a shell might burst in that very room.” The capital’s inhabitants would not rest easy until the U.S. Army occupied the heights.

New York Illustrated News One might expect that the first Union soldiers to arrive at Arlington might take revenge against a man they believed a traitor to their country. Yet the first two men to make their headquarters on the property adopted an entirely different policy. In an official dispatch on May 28, General Charles W. Sandford of the New York volunteers reported, “Finding the mansion vacated by the family, I stated to some of the servants [enslaved people] left there that had the family remained I would have established a guard for their security from annoyance; but, in the consequence of their absence, that I would, by occupying it myself, be responsible for the perfect care and security of the house and everything in and about it.” Sandford did not make this statement solely out of respect to General Lee or his family. More practically, several Union military leaders, including Winfield Scott, believed that if they damaged the property of southern civilians they would build up animosity toward the federal government and possibly prolong the rebellion. Thus, one of Sandford’s first acts after establishing his headquarters was to issue a proclamation to local citizens guaranteeing that federal troops “will be employed for no other purpose than that of suppressing unlawful combinations against the constituted authorities of the Union.”

Library of Congress. Despite these assurances, one person remained displeased. Furious that the Union Army had seized her childhood home on the “pretext” of defending the capital, Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee wrote a caustic letter to the commander of the occupying forces. “It never occurred to me Genl Sanford that I could be forced to sue for permission to enter my own house & that such an outrage as its military occupation to the expulsion of me & my children could ever have been perpetrated by any one in the whole extent of this country.” By the time the letter arrived at Arlington House, a new commander had taken Sandford’s place – General Irvin McDowell, a friend of Robert E. Lee who graduated in the same class at West Point. Perhaps because of this prior relationship, he took the unusual step of writing directly to the rebel general’s wife to assure her he was protecting her property. “With respect to the occupation of Arlington by the United States troops, I beg to say it has been done by my predecessor with every regard to the preservation of the place. I am here temporarily in camp on the grounds, preferring this to sleeping in the house, under the circumstances which the painful state of the country places me with respect to its proprietors.” Further testifying to his desire to protect civilian property, when Selina Gray, Arlington’s enslaved housekeeper, informed McDowell that a locked cellar room containing relics from George Washington had recently been broken into, he took possession of the artifacts to prevent his soldiers from stealing or damaging them. He later sent the relics to the U.S. Patent Office for safekeeping. Although she strongly resented the way the Army treated her house, Mary Lee nevertheless admitted after the war that unlike other commanders, “I have been told that Genl Mac Dowell scrupulously protected it during his occupation.”

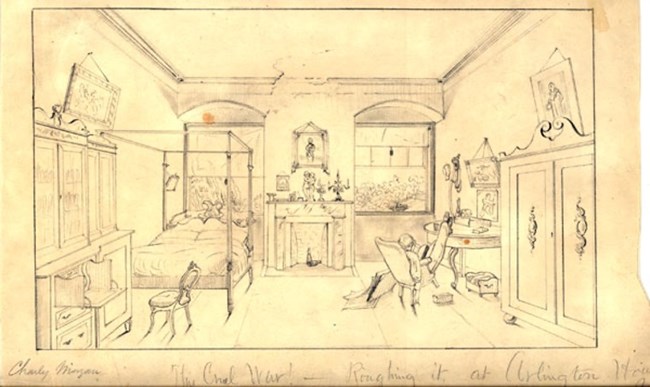

Library of Congress. McDowell’s tenure at Arlington House concluded a few months after his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). With the Union Army routed, the newly constructed defenses on Arlington Heights were the only barrier between the Confederates and Washington, D.C. Fortunately for the Union, the Confederate Army was unable to advance any further. When McDowell was relieved of his command, General George B. McClellan became the next officer to head Arlington’s military encampment. He spent the winter of 1861-62 drilling his army to prepare them for campaigns in the springtime. During that winter, soldiers entered Arlington House and made themselves at home in some of the Lee family’s most personal spaces. One soldier named Charly Morgan sketched the Lee girls’ bedroom as one of his comrades placed his feet on their table. Others left their mark in the form by writing messages and names on the walls which are still visible today.

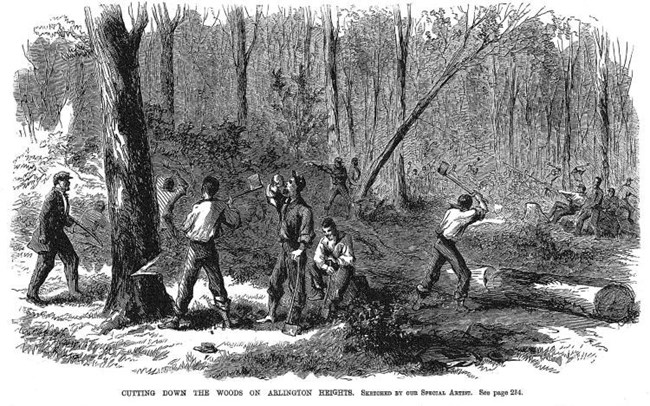

NPS Image. The Union occupation entirely transformed the Arlington property. The vast forests that surrounded the mansion house were cleared for encampments and defenses. They cut down so much woodland that after the end of the war, Selina Gray wrote that “there is not a tree to be seen except in the cemetery.” Addressing the lack of housing for formerly enslaved people in Washington, the Army established the Freedman’s Village, near what is now Section 25 of Arlington National Cemetery. Most notably, General Montgomery C. Meigs transformed the property into a military cemetery, as it remains today.

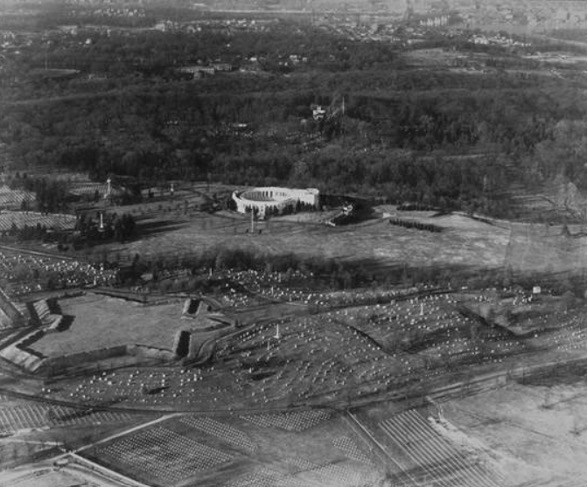

Library of Virginia. Attempting to fill a crucial gap between Fort Whipple and Fort Albany to the southeast, the Union ordered the construction of another defensive work, Fort McPherson. Begun by United States Colored Troops in 1864, it remained unfinished through the war. For many years, the incomplete earthworks could be seen near the modern Memorial Amphitheatre, as shown in the photograph below. Needing space for additional graves, in 1947, cemetery officials razed the fort’s remains to create Section 11. The boundaries of this section, between McKinley Drive and McPherson Drive, correspond almost exactly the perimeter of Fort McPherson. |

Last updated: November 3, 2020