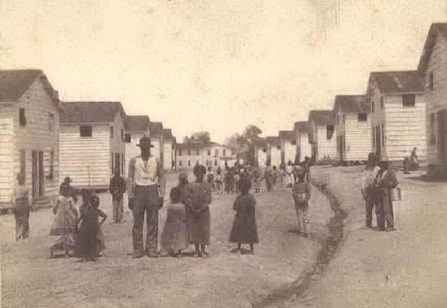

Oshkosh Public Museum, Oshkosh, WI On April 16, 1862, Congress passed legislation freeing all enslaved people in the District of Columbia. African Americans from Virginia and elsewhere flocked to the city in search of work and shelter. Already struggling to meet the needs of their impoverished residents by the fall of 1862, the modest freedmen’s camps which the Government had erected in the city were overwhelmed after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all enslaved people in the Confederate states January 1, 1863.[1] Overcrowding and steadily deteriorating conditions in the Washington camps drove military authorities to look to create a new camp for “contrabands,” outside of the city.[2] Removed from Washington and occupied by the Union army since with start of the Civil War in 1861, Arlington emerged as a sensible choice for the new camp. On May 5, 1863, Lieutenant Colonel Elias M. Greene, chief quartermaster of the Department of Washington, and Danforth B. Nichols of the American Missionary Association officially selected the Arlington Estate as the site for Freedmen’s Village, which they intended to be a model community for freedpersons. As Greene wrote to Major General S. P. Heintzelman in 1863, the creators believed that the open air would improve the health of the freedmen and have other benefits: “There is the decided advantage afforded to them of the salutary effects of good pure country air and a return to their former healthy avocations as field hands under much happier auspices than heretofore which must prove beneficial to them and will tend to prevent the increase of disease now present among them.”[3] Within a few weeks, 100 formerly enslaved people settled on the chosen site, located about one half mile to the south of the Arlington mansion.[4] The following December, Freedmen’s Village was officially dedicated with a ceremony attended by members of Congress and other notables. The symbolic power of transforming part of the Confederate General’s plantation estate into a community for freedmen likely served as a motivation for Greene, Danforth and other Washington officials in charge of creating the village.[5] For many abolitionists and some in the Government, Robert E. Lee, as the leading Confederate General, came to personify slavery and unrealized freedom for millions of African Americans in America. The use of his home as a camp for freedpersons was, thus, thought to be very appealing and appropriate by many in the north. The local Republican press recognized that the location of Freedmen’s Village was no accident. Under the headline, “Gen. Lee’s Lands Appropriately Confiscated” the Washington, D.C. Morning Chronicle cheered:

As it developed, the design and layout of the village were intended to create a climate of order, sobriety and industry, consistent with the War Department’s goal of making the formerly enslaved people self-sufficient.[7] An 1865 plan of the settlement shows a very organized community with over fifty residences, a hospital, kitchen/mess hall, school house, “old people's home” and laundry, amongst other structures, neatly arranged around a central pond. As noted and illustrated in Harpers Weekly, many of these structures were already in place in the spring of 1864. While the physical layout of the village may have developed in line with the ideas of the community’s creators, the nature of life at Freedmen’s Village proved to be a great departure from this vision. The War Department intended for the Village to be a temporary refuge where residents would be taught vocations and receive a basic education before leaving to find work elsewhere. Quickly, however, population boomed as residents became attached to the community. The village turned into a semi-permanent settlement and the government developed facilities and infrastructure to support the several thousand residents.[8] Able adult tenants who did not have work elsewhere worked on the government farms which occupied the acreage surrounding the village at Arlington. In exchange for their work, the laborers were paid ten dollars per month, half of which they were required to pay to a general fund to maintain the village.[9] Some residents came to resent the strict policies and rigid lifestyle which was enforced upon them by the Army and, later, the Bureau of Refugees, Freemen and Abandoned Lands, which took over administration of the village in 1865. The issue of property rents became a particularly divisive one. To help support the village, officials from the Freedmen’s Bureau imposed a rent on the tenants. Some freedpersons viewed this rent, which ranged from one to three dollars per month, as an unnecessary burden in their quest to gain self sufficiency and protested by refusing to pay the required sum.[10] Rent collection became a serious problem as an inspector complained in his May 1866 report to General C.H. Howard, who oversaw the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau at Arlington: “The directions from these Head Quarters requiring all parties renting land on the farm and occupying tenements at Freedman’s Village to pay their house rent monthly in accordance have not been obeyed. Twenty-three of these tenants live at the village but few of which have paid any rent though it was due from all the first of the current month.”[11] Despite difficulties rents became a constant of life in the village over time. Tension over rents was only a precursor to other, more serious, issues which residents faced later. As early as 1868, the Federal Government attempted to close Freedmen’s Village. The movement to disband the village grew stronger in subsequent years as the property at Arlington became more and more desirable for development and public support for the freedmen’s community there waned. Utilizing their newly-acquired rights, the residents organized politically and successfully delayed disbanding efforts for a number of years. Even by the late, 1880s when eviction was inevitable, the residents continued to fight, electing a committee to petition the Government regarding their unique situation. John Syphax, whose mother had been enslaved at Arlington, was chosen to present the committee’s views to the Secretary of War. In a letter to the Secretary in 1888, Syphax asserted that the freedpersons at Arlington should be compensated for the improvements which they had made to the property, and requested a settlement of $350 for each homeowner on the estate. He closed his letter with the following statement, simultaneously reflective of both the improved political rights afforded to African Americans following the Civil War and the gulf which still existed between black and white Americans: “Twenty-four years residence at Arlington, with all the elements involved in this case inspire the hope that full and ample justice will be done even to the weakest members of this great republic.”[12] The Government would eventually compensate the residents $75,000—the appraised value of the dwellings on the property in 1868 and the contraband-fund tax which had been collected during the Civil War—in finally closing Freedmen’s Village in 1900. In spite of the issues and challenges which faced residents, and the eventual closure of the village, living at Freedman's Village was the first experience of a life out of bondage for thousands of African Americans, including a number of the people formerly enslaved at Arlington. Here, on the grounds of a plantation estate that had been built and maintained by the labor of enslaved people, residents began a new phase in their experience which they had a heightened measure of control over their lives. With legal rights and freedoms these people could, at least partially, determine their own destinies. In that sense, the experience of the community's residents, in finally realizing some of the promises of American freedoms while living at Arlington was an appropriate precursor to what the Arlington estate would become; a national memorial ground remembering the sacrifices of thousands who sacrificed tremendously to defend the very freedoms which the freedmen first experienced on the Arlington grounds.

References [1] Joseph P. Reidy, “Coming form the Shadow of the Past: The Transition from Slavery to Freedom at Freedmen’s Village, 1863-1869,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 95, No. 4 (October 1987), 405-406. [2] Camp Barker, the main camp for refugees in Washington, averaged 25 deaths per week in 1863, due primarily to outbreaks of disease such as scarlet fever, measles, and whooping cough. At Freedman’s Village, the mortality rate dropped considerably—to two per day. See Reidy, 407 and Roberta Schildt, “Freedman’s Village: Arlington, VA, 1863-1900,” The Arlington Historical Magazine, Vol. 7, No. 4, (October 1984), 15. [3] Letter, Col. Elias M. Green to Major Gen. S.P. Heintzelman, May 5, 1863. National Archives, RG 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Records Relating to Functions: Cemeterial, 1829-1929. General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries (“Cemetery File”), 1865-c.1914. Arlington, VA. Box 7, NM-81, Entry 576. [4]Schildt, 11. [5] Commenting on this point, Joseph Reidy argues: “The irony of former slaves building a life of freedom on the Lee family’s property tasted sweet to Washington officials and northerners in general.” See Reidy, 417. [6] Morning Chronicle, June 17, 1864. [7]Reidy, 411. [8] “‘We have a claim on this Estate,’ Arlington from Slavery to Freedom,” (Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2000), 7. [9]Reidy, 411. See also, “We have a claim on this Estate…,” 8. [10]Reidy, 413. [11] Letter, M. Clark. to Gen. C.H. Howard, May 31, 1866. National Archives RG 92: M1055, Roll #6, Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1869, Letters Received, May-Oct. 1866, 14100-2419. [12]Letter, John Syphax to Sec. W.C. Bodicott, Jan. 18, 1888. Copy printed in Freedmen's Village: Arlington, Virginia, 1863-1900, (Arlington, VA:ArlingtonPublic Schools, 1983), 62-64. Original at National Archives. |

Last updated: February 13, 2024