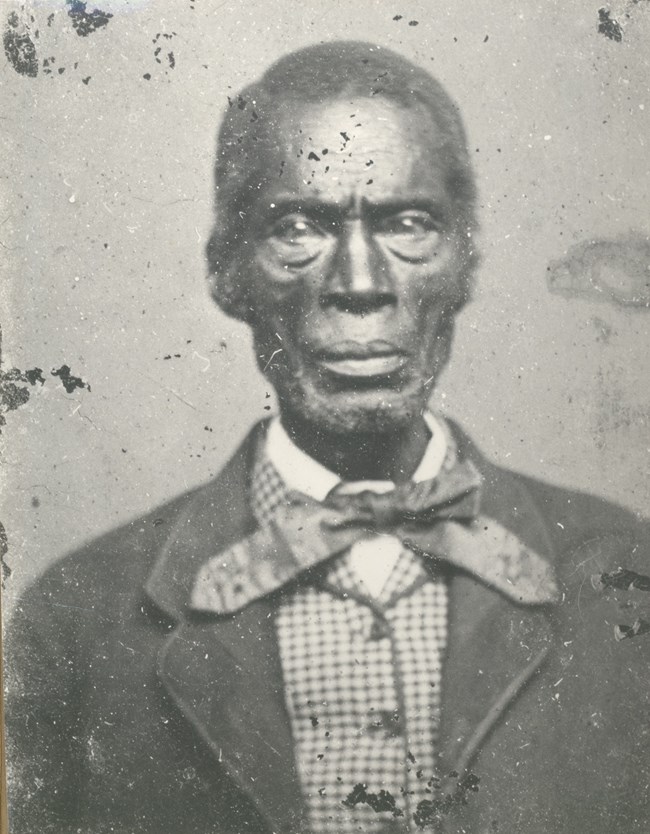

NPS Image From its earliest days, Arlington House was home not only to the Custis and Lee families who occupied the mansion, but also to dozens of enslaved people who lived and labored on the estate. For nearly sixty years, Arlington functioned as a complex society made up of owners and enslaved people, whites and blacks. To some observers, on the surface, Arlington appeared as a harmonious community in which the owners and enslaved people often lived and worked side by side. Yet an invisible gulf separated the two, as enslaved people were the legal property of their owners. The enslaved possessed no rights, could not enter into legally binding contracts, and could be permanently separated from their families at a moment's notice. The contributions of the Arlington enslaved people have been a vital component of Arlington House's history from the beginning. In 1802, the first slaves to inhabit Arlington arrived at the estate with their owner, George Washington Parke Custis. The grandson of Martha Washington and step-grandson of George Washington, Custis was adopted by the Washingtons and had grown up at Mount Vernon, as had many of his enslaved people. Upon Martha Washington's death, Custis inherited her enslaved people and purchased others who belonged to his mother, Eleanor Custis Stuart. In all, Custis owned nearly 200 enslaved people and as many as 63 lived and worked at Arlington. (The others worked on his other two plantations, White House and Romancoke, located on the Pamunkey River near Richmond, Virginia.) Once at Arlington, the enslaved people constructed log cabins for their homes and began work on the main house. Using the red clay soil from the property and shells from the Potomac river, they made the bricks and stucco used in the walls and exterior of the house. The enslaved people also harvested timber from the Arlington forest, which was used for the interior flooring and supports. Day to day, the enslaved people were responsible for keeping up the house and laboring on the plantation, working to harvest corn and wheat which was sold at a market in the city of Washington. Some enslaved people had very close relationships with the Lee and Custis members, though these relationships were very much governed by the racial hierarchy which existed between the enslaved and slaveholders. Mr. Custis relied heavily on his carriage driver, Daniel Dotson, and Mrs. Lee had a very personal relationship with the head housekeeper, Selina Gray. As Mary's arthritis increasingly restricted her activities through the years, she depended on Selina for assistance with basic tasks. A reflection of their relationship, Mrs. Lee entrusted Selina with the keys to the plantation at the time of the Lees' evacuation from Arlington in May 1861. There is evidence that some enslaved people at Arlington had opportunities which were not widely afforded to enslaved people elsewhere. Mrs. Custis, a devout Episcopalian, tutored enslaved people in basic reading and writing so that each could read the Bible. Mrs. Lee and her daughters continued this practice even though Virginia law prohibited the education of enslaved people by the 1840s. Mrs. Custis also persuaded her husband to free several women and children. Some of these emancipated enslaved people settled on the Arlington estate, including Maria Carter Syphax who lived with her husband Charles on a seventeen acre plot given to her by the Custises at the time of her emancipation around 1826. While such allowances may have improved the quality of life for the Arlington enslaved people, most black men and women on the estate remained legally in bondage until the Civil War. In his will, George Washington Parke Custis stipulated that all the Arlington enslaved people should be freed upon his death if the estate was found to be in good financial standing or within five years otherwise. When Custis died in 1857, Robert E. Lee—the executor of the estate—determined that the slave labor was necessary to improve Arlington's financial status. The Arlington enslaved people found Lee to be a more stringent taskmaster than his predacessor. Eleven enslaved people were “hired out” while others were sent to the Pamunkey River estates. In accordance with Custis's instructions, Lee officially freed the enslaved people on December 29, 1862. In 1863, Federally-supported Freedman's Village, a camp for formerly enslaved people, was established on the Arlington estate, south of the mansion. Over the next 30 years, many freedman, including some of the former Custis slaves, established permanent homes in Freedman's Village where they learned trades and attended school. Though Freeman's Village closed by 1900, the contributions of the formerly enslaved people who worked to build and shape the Arlington estate are not forgotten. Some settled locally and many of their descendants still live in Arlington County today. |

Last updated: August 7, 2020