Library of Congress Robert E. Lee's pacing could be heard from downstairs. He had retired to his bedroom where the internal struggle between loyalty to state or nation would be decided. Eventually the pacing ceased. When the footsteps resumed Lee was descending the stairs, holding two letters. He handed the letters to his wife saying, “Well Mary, the question is settled. Here is my letter of resignation, and a letter I have written to General Scott.” Robert E. Lee's resignation from the U.S. army in the early morning hours of April 20, 1861 would bring to an end to the thirty year relationship between Lee and Arlington House. Within two days he would board a train bound for Richmond, never to return. His wife did not accompany him and remained at Arlington House to await developments reluctant to abandon her family's ancestral home. She would not remain for long, however. Within five days of departing for Richmond Lee wrote his wife, “War is inevitable, and there is no telling when it will burst around you….You have to move and make arrangements to go to some point of safety which you must select.” As the weeks progressed and Union forces began concentrating in Washington it became more apparent that Mrs. Lee would have to prepare her House for evacuation. Mrs. Lee had no intention of permanently abandoning the House and was slow at first to act upon her husband's advice. In a letter to her daughter Mildred on May 5, she stated, “I would not stir from this house, even if the whole northern army were to surround it.” On May 11, she referred to her husbands worries. “Were it not that I would not add one feather to his load of cares,” she would have remained at Arlington come what may. In the end, however, it was Robert E. Lee's concerns and a report of immediate occupation that drove her to evacuate. The warning shot across the bow came in early May in the form of Orton Williams, a cousin who came to Arlington House with alarming news. He warned Mrs. Lee that she must pack up her valuables immediately as the Union army was preparing to cross the Potomac and occupy Arlington in a matter of hours. Though Orton's warning turned out to be a false alarm, it was an event that crystallized the need to prepare the house for an orderly evacuation. Mrs. Lee's arthritis restricted her role in the physical work of preparing the house for evacuation but she supervised the hasty preparations. The family silver was packed away along with the personal papers of George Washington, her father George Washington Parke Custis and her husband Robert E. Lee and were sent to Richmond. Mrs. Lee informed her husband of the evacuation's progress on May 9, 1861. “I suppose ere this, dear Robert, you have heard of the arrival of our valuables in Richmond. We have sent many others to Ravensworth & all our wine & stores, pictures, piano etc.” Six days later, on May 15, 1861, Mrs. Lee entrusted the keys to the house to Selina Gray, the enslaved housekeeper, and the Lees left Arlington. The family headed first to the White House Plantation and eventually on to Richmond. Selina and the rest of the enlaved people at Arlington were to run the estate as though the Lees were to any day return. On May 23, 1861 Virginians voted 96,750 yay, 32,134 nay, in favor of secession. The next day, the United States Army crossed the Potomac and occupied the defensible ground around Washington, including the Arlington Estate. Arlington House itself was not immediately occupied by Union forces. Arlington Then and Now

Left image

Right image

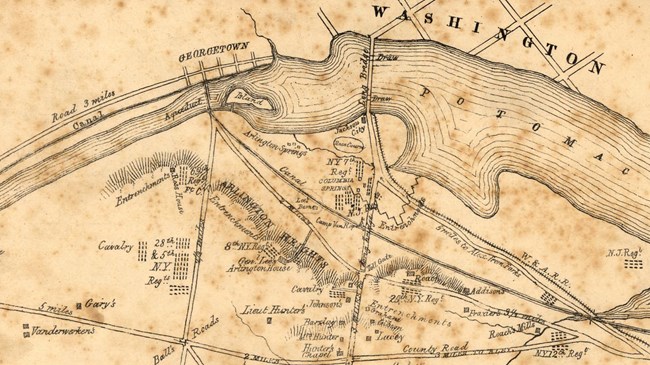

Library of Congress A few weeks after her family's evacuation, Mrs. Lee corresponded with the Union army commander General McDowell and he assured her that the house had not been occupied and that he would do his utmost to protect it. He could not make similar assurances about the 1,100 acres which surrounded the house. Fortifications were constructed, military roads built and trees cut down to clear lines of fire. Such actions were redoubled as the Union Army reorganized after its defeat at Manassas in July 1861. By the war's end, two forts, Whipple and McPherson, stood on the northwest portion of the Arlington estate and three other forts were constructed to the west and south of the estate. With the illusion of a short war shattered at Manassas in the summer of 1861 the necessities of war trumped McDowell's earlier assurances to Mrs. Lee regarding Arlington House. The enlarging the Union army's staff and strengthening the defensive lines around Washington required that Mrs. Lee's house could not be allowed to go unused by the Union Army. Eventually, Union officers took up residence in the house and Mrs. Lee's home was transformed into a military headquarters. In a letter to his wife on Christmas Day 1861 Lee commented upon the changes war would likely bring to Arlington. “As to our old house, if not destroyed, it will be difficult even to be recognized. Even if the enemy had wished to preserve it, the change of officers, the want of fuel, shelter etc, all the dire necessities of war, it is vain to think of its being in a habitable condition. I fear too, books, furniture & the relics of Mt. Vernon will be gone. It is better to make up our minds to a general loss. They cannot take away the remembrances of the spot, & the memories of those that to us render it sacred. That will remain to us as long as life will last, & that we can preserve.” In January 1862 a Wisconsin soldier's description of the Arlington house rang true to Lee's prediction. “The grand old southern homestead of Arlington, with its quaint and curious pictures on the wall, its spectacular apartments, broad halls and stately pillars in front, was an object of especial interest; but, abandoned by its owner, General Robert E. Lee, who was using his great power as a military leader, to destroy the Government he had sworn to defend, it was now a desolation. The military headquarters of McDowell's division was in the Arlington House, which was open to the public and hundreds tramped at will through its apartments.” Arlington would never be the same. |

Last updated: August 7, 2020