Lee’s Views on Union and Secession The Lee and Custis families were well known supporters of the American Union. George Washington Parke Custis, the step grandson of George Washington, promoted the importance of the federal government and the union of states in numerous speeches and writings throughout the early 19th century. In 1831, a young Robert E. Lee (the son of “Light Horse Harry” Lee) married George Washington Parke Custis’ daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis and they made their home at Arlington. Robert E. Lee, an officer in the United States Army, was also a strong proponent of the Constitution and the American Union, as his father had been. As the nation approached Civil War in the late 1850s and early 1860s, Robert E. Lee continued to hope for the continuation of the Union and peace between the states. When South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, Lee was stationed with the U.S. Army in Texas. In January 1861, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and Louisiana all seceded from the Union. Texas followed shortly after in February and a new government, the Confederate States of America, was created in Montgomery, Alabama. Lee opposed secession. He wrote that “. . . I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. I hope therefore, that all constitutional means will be exhausted before there is a recourse to force. Secession is nothing but revolution.”[1] However much he opposed secession though, he believed that “a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me. I shall mourn for my country and for the welfare and progress of mankind. If the Union is dissolved, and the Government disrupted, I shall return to my native State and share the miseries of my people, and save in defense will draw my sword on none." [2]

In February 1861, Lee was transferred back to Washington, DC, and arrived at his Arlington home on March 1, 1861. On March 28, Lee was promoted by the new President Abraham Lincoln to full colonel in the army. Lee accepted his new commission and still hoped that Virginia would stay in the Union and that war would be averted. Lee watched closely at the debates raged in Virginia over secession. Virginia’s secession convention voted overwhelmingly to stay in the Union on April 4, 1861. This vote occurred as a standoff was occurring between Confederate forces and the U.S. Army at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. On April 12, 1861, as U.S. ships moved to resupply and reinforce the garrison at the fort, the Confederates opened fire on the Union garrison. On April 14, the garrison surrendered the fort to the Confederacy. The next day in Washington, DC, Lincoln called upon 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Southern Confederacy.

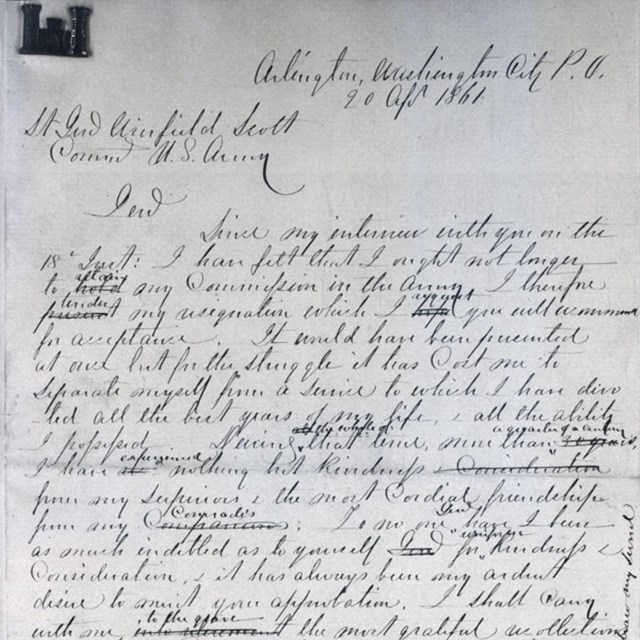

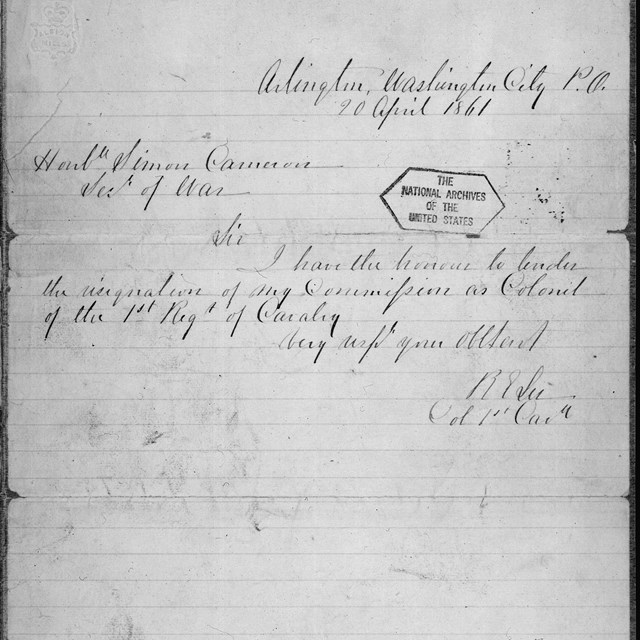

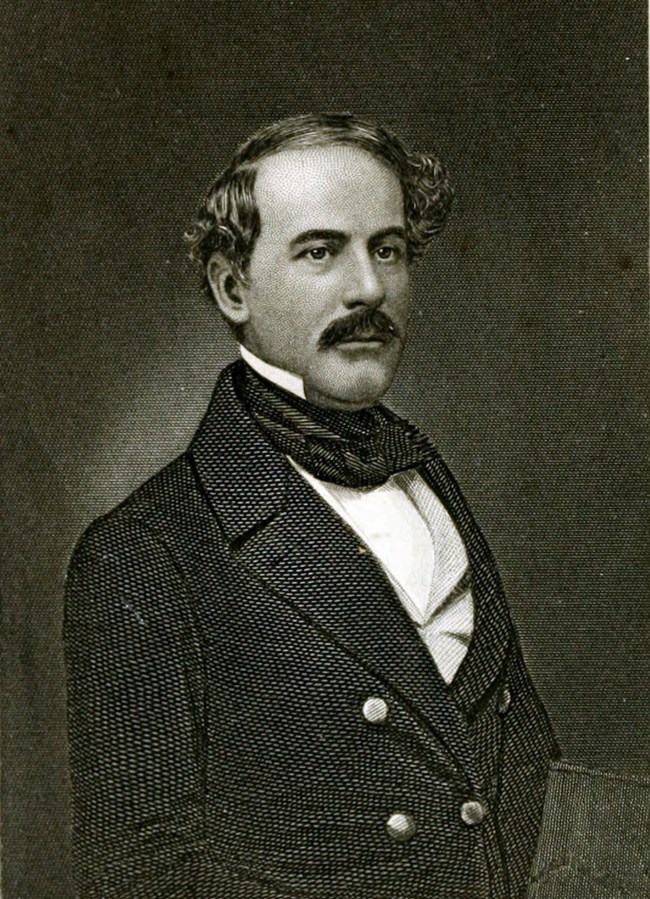

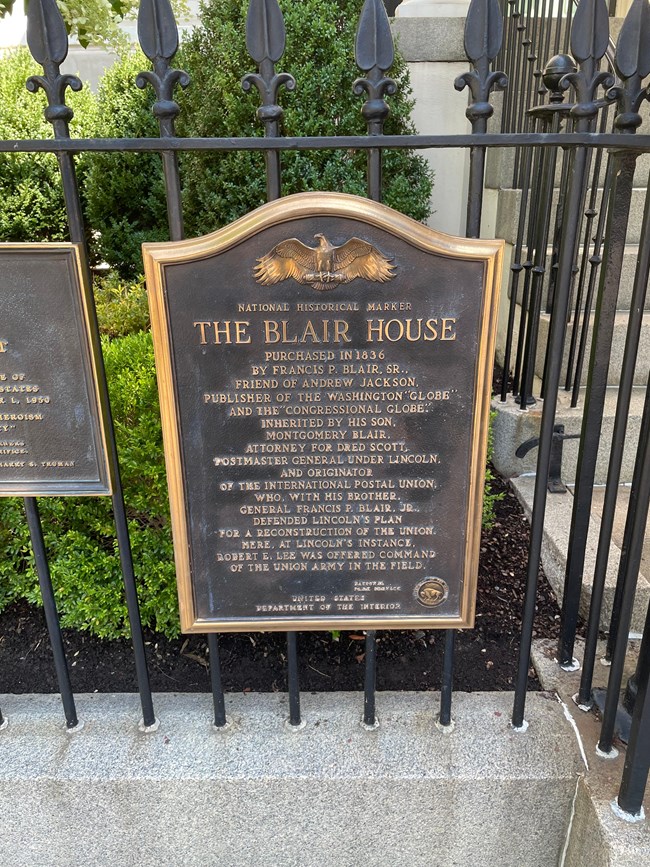

NPS Lee Offered Command of Union ForcesOn April 18, 1861, Lee was invited to the home of his friend Francis Preston Blair near the White House in Washington, DC. Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Blair were interested to see if Lee would accept command of the army gathering in Washington, DC. Without hesitation, Lee refused. He wrote that "I declined the offer he made me to take command of the army that was to be brought into the field, stating as candidly and as courteously as I could, that though opposed to secession and deprecating war, I could take no part in an invasion of the Southern States." [3] Blair wrote that Lee "said, among other things, that he would do everything in his power to save it, and that if he owned all the negroes in the South, he would be willing to give them up and make the sacrifices of the value of every one of them to save the Union.” [4]Robert E. Lee’s daughter, Mary Lee, wrote that “I remember him saying to me subsequently, ‘I told Mr. Seward that if he could give me the whole four millions of slaves into my own hands tomorrow, they would not weigh one moment in the balance against the Union. That I was not contending for the perpetuation of slavery’—or words to that effect.” [5] After refusing command, Lee immediately went over to the War Department to meet with his old mentor, friend, and commanding officer, General Winfield Scott. Upon learning of Lee’s refusal to take command of the army, Scott said "you have made the greatest mistake of your life; but I feared it would be so." [6] Scott then suggested Lee should resign if he would not follow orders to join in the approaching war. Lee met with his brother Sidney Smith Lee (an officer in the U.S. Navy) to discuss what they should do. They make no decision and Lee returned to Arlington. Lee still had not learned what course Virginia would ultimately take. The Severest StruggleOn April 19, 1861, Lee went down to Alexandria with his wife and daughter Mary. While in town, Lee learned that the Virginia secession convention switched course after Lincoln called up troops and officially voted to secede from the Union. There would be an official referendum by the citizens of Virginia on May 23, but it appeared clear to most that Virginia would leave the Union. Lee remarked to the druggist at the apothecary in town that "I must say that I am one of those dull creatures that cannot see the good of secession." [7]Lee returned to Arlington where he had to decide what to do. He did not want to leave the Army he had served in for more than 30 years, and he loved the Union. However, he was not able to justify leading men in a war against his native state. Lee contemplated his options for hours. Enslaved people like James Parks remembered Lee pacing on the portico saying he “didn’t care to go.” [8] Visiting the Lees that day was a five-year-old George Lyttleton Upshur, who remembered watching Lee pace in the garden, and then that night the family listened as he paced back and forth in his bedroom. [9] They would hear him occasionally fall to his knees in prayer. His wife Mary recalled that this as “the severest struggle of his life.” [10] Sometime shortly after midnight in the early morning hours of April 20, 1861, Lee decided to resign his commission. He wrote a brief resignation letter to the Secretary of War and then wrote a longer letter to Winfield Scott. He gave these letters to the enslaved man Perry Parks to see that they made it to Washington, DC. He also wrote letters to his sister in Baltimore, his brother, and his cousin explaining his course of action. In all of his letters he writes that his decision to resign was based on not being able to “raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home” and that “save in defence of my native State, I never desire again to draw my sword.” [11] After breakfast on April 20, Lee received news of the riots that occurred in Baltimore on the previous day and resulted in the deaths of some Southern civilians and Federal troops. One of the Southern civilians killed (Robert W. Davis) was an acquaintance of Lee’s daughter Mary. After receiving this news, Lee gathered his family in his office and explained to them that he had resigned. The news was received with stunned silence. Lee said: “‘I suppose you all think I have done very wrong”, to which his daughter Mary said, “Papa, I don’t think you have done wrong at all.” [12] That afternoon, Orton Williams (a member of Scott’s staff and cousin of the Lees), rode to Arlington and told them that many officers were resigning and that Scott took Lee’s resignation with much difficulty. Scott laid on a sofa and mourned as though he lost a son.

NPS Lee Leaves ArlingtonThe next day Lee went to Christ Church in Alexandria and attended church. He was supposed to meet Judge John Robertson, a Virginia judge sent by the Virginia Governor John Letcher, who requested to meet with Lee after the church service. However, Robertson got held up in another meeting in Washington, DC. Lee returned home to spend his last night at Arlington. That evening he learned in a letter from Robertson that the Governor of Virginia wanted to meet with Lee in Richmond the next day.On April 22, Lee left Arlington for the last time never to return. He went down to the train station at Alexandria where he met with Judge Robertson and traveled to Richmond. That evening in Richmond Governor Letcher offers Lee command of Virginia’s military forces. Lee, in his third important decision that week (after refusing federal command and resigning his commission) accepts the command. The next day, on April 23, Lee was escorted to the Virginia capitol building. Standing in the rotunda of the capitol, he looked up at Houdon’s famous statue of George Washington before being introduced to the Virginia convention. John Janney, the president of the convention, officially welcomed Lee and symbolically presented him with command of Virginia’s military. Janney introduced Lee: "When the Father of his Country made his last will and testament, he gave his swords to his nephews with an injunction that they should never be drawn from their scabbards, except in self-defense, or in defense of the rights and liberties of their country, and that, if drawn for the latter purpose, they should fall with them in their hands, rather than relinquish them. Yesterday, your mother, Virginia, placed her sword in your hand upon the implied condition that we know you will keep to the letter and in spirit, that you will draw it only in her defense, and that you will fall with it in your hand rather than that the object for which it was placed there shall fail." [13] Lee responded: “Profoundly impressed with the solemnity of the occasion, for which I must say I was not prepared, I accept the position assigned me by your partiality. I would have much preferred had your choice fallen on an abler man. Trusting in Almighty God, an approving conscience, and the aid of my fellow-citizens, I devote myself to the service of my native State, in whose behalf alone will I ever again draw my sword.” [14] Impact of Lee’s ResignationLee ended up playing a crucial role in how Civil War was fought. Some historians said the decision he made to resign from the US Army was “the decision he was born to make”, while others called him a traitor for not standing by the Union. It was clear however, that Lee’s decisions ultimately cost him and his family almost everything. While he would later work for reunion and reconciliation after the war, he never doubted the decision he made at Arlington in April of 1861. Lee said after the war, "I did only what my duty demanded. I could have taken no other course without dishonor. And if it all were to be done over again, I should act in precisely the same manner." [15]

Notes: [1] Nolan, Alan T. Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. 34. [2] Horn, Jonathan. The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee's Civil War and His Decision That Changed American History. New York: Scribner. 102. [3] Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee: A Biography, Volume I. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935. 633. [4] Ibid., 634. [5] Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. “Thou Knowest Not the Time of Thy Visitation”, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography; Richmond Vol. 119, Iss. 3, 2011. 277-296. [6] Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Volume I. 437. [7] Guelzo, Allen C. Robert E. Lee: A Life. New York: Penguin Random House, 2022. 190. [8] Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters. New York: Viking Press, 2007. 291. [9] Upshur, George Lyttleton. As I Recall Them: Memories of Crowded Years. New York: Wilson-Erickson, 1936. 16-17. [10] deButts Jr., Robert E. L. Mary Custis Lee's "Reminiscences of the War". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography; Richmond Vol. 109, No. 3. 2001. 301-325 [11] April 20 letters [12] Pryor. “Thou Knowest Not the Time of Thy Visitation”. 277-296. [13] Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Volume I. 467-68. [14] Ibid. [15] Ibid., 447. |

Last updated: April 19, 2024