Library of Congress In the years following the Civil War, Robert E. Lee became one of the most memorialized figures of the former Confederacy. Memorials were not just statues and monuments. Well into the twentieth century, White Southerners created roads, museums, and books to celebrate Lee’s character and accomplishments. But the memorials did not all tell the same story of Robert E. Lee. The memory of Lee changed over time as each new generation re-wrote the history of Lee and the Confederacy. For example, some former Confederates argued that Lee was a Confederate to his last breath. Other biographers highlighted Lee’s attempts to restore the Union after the Civil War. Between 1865 and the 1930s, memorialists transformed Lee from a Confederate icon to a figure of national unity. The changes in perspectives of Lee were particularly important in the creation of the Robert E. Lee Memorial at Arlington House. Arlington House is one of the more dynamic examples of the changing meanings of Robert E. Lee memorials. Robert E. Lee’s Thoughts on Confederate MemorialsThe complex relationship between Robert E. Lee and memorials began in Lee’s lifetime. He argued against creating Confederate war monuments on battlefields, which would “keep open the sores of war.” [1] Instead, Lee supported efforts by Ladies Memorial Associations to mark the graves of Confederate casualties. “As regards the erection of such a monument as is contemplated: my conviction is, that however grateful it would be to the feelings of the South, the attempt in the present condition of the Country would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating its accomplishment; & of continuing , if not adding to, the difficulties under which the Southern people labour. All I think that can now be done, is to aid our noble & generous women in their efforts to protect the graves & mark the last resting places of those who have fallen, & wait for better times.” [2] These local groups led post-war efforts to establish Confederate cemeteries and hold remembrance ceremonies like Confederate Memorial Day. Lee’s Death and the Early Lost CauseLee’s death in 1870 inspired former Confederates to begin creating memorials to Lee. As the news spread, families hung black cloth and governments flew flags at half-staff. Former soldiers, politicians, and women’s groups immediately formed Lee memorial associations in Lexington and Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans. Each association tried to control the legacy of Lee and his role in the Confederacy. Former Confederate general, Jubal Early, was the most powerful figure in Lee memorialization. He led Richmond’s Lee Monument Association and co-founded the Southern Historical Society. Early was determined to create a pro-Confederate history of the Civil War that vindicated the Southern cause. One contemporary wrote that, “no man ever took up his pen to write a line about the great conflict without the fear of Jubal Early before his eyes.” [3] This pro-Confederate history was widely known as the Lost Cause. The primary idea of the Lost Cause was that the South had fought a righteous war for states’ rights. These former rebels blamed the conflict on Northern military aggression while praising the virtuous Southern secession. Confederate memorialists considered antebellum Southern agrarian society as morally superior to Northern industrialism. Slavery was present as a humane and Christian institution but not the cause of the war. Veterans proclaimed that the Confederate armies were not beaten in battle but subdued by the overwhelming weight of Northern materialism. [4] The Lost Cause became more openly accepted among white Southerners as federal power weakened towards the end of Reconstruction. White Southerners began to openly justify the Confederate war effort and to express political hostility and racism towards the Reconstruction policies of Union military occupation and black political participation. Throughout the 1870s, these Lost Cause groups marketed Lee’s celebrity across the South. Popular biographies and lecture series praised Lee’s military and moral virtues. Southern families purchased pictures of Lee to raise funds for monuments. Scholars have dubbed these early groups focused on Lost Cause memory and Lee’s celebrity as the first “Lee cult.” [6]

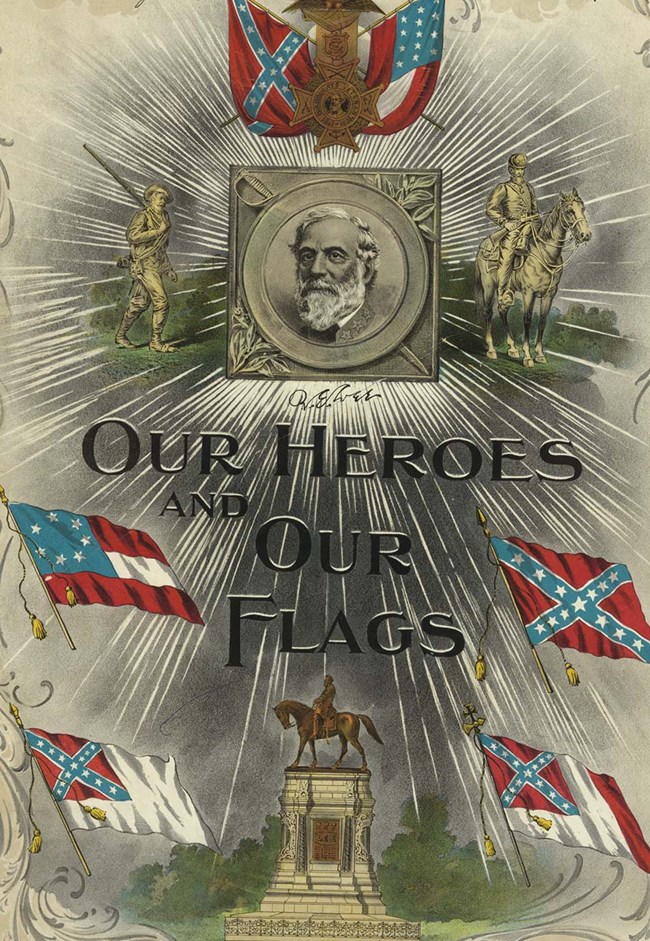

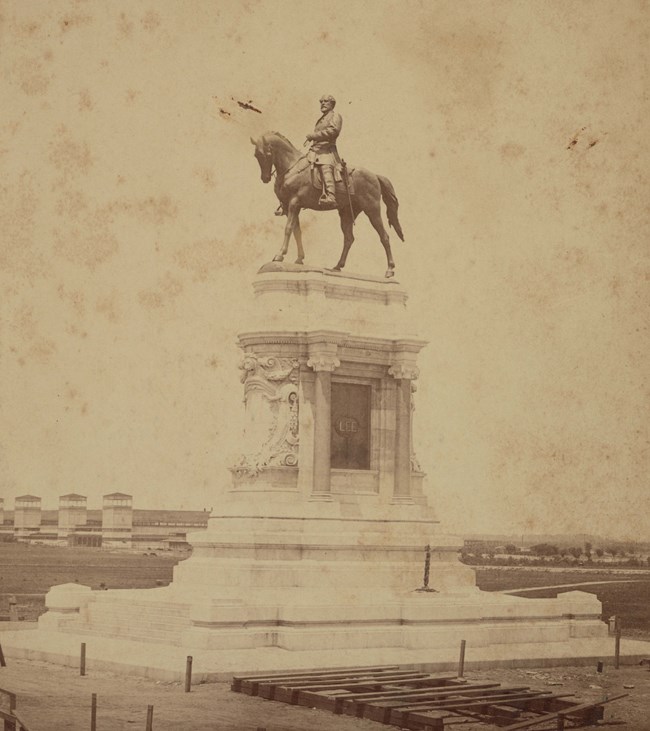

Library of Congress Building Public Monuments to LeeThe visual markers of this first Lee Cult came in a series of Lee monuments. The first monument completed was the “Recumbent Lee” in 1883 in Lexington. In New Orleans, the Lee Monumental Association erected the first large public monument in 1884. The Lee equestrian statue in Richmond was finished in 1890, with 100,000 in attendance. Northern critics expressed concern for these large public monuments. The Minneapolis Tribune called Lee an “unnatural demigod of the slaveholding South.” Black newspapers felt the statues re-opened old wounds and taught the young generation of Southerners a white-washed history of the Confederacy. [7] In fact, during the 1890s, Lee and Confederate memorials became much more public symbols of Lost Cause history. A new generation of white Southerners were determined to celebrate the cause of their parents and maintain a distinctive southern cultural identity. Several former Confederate states established Robert E. Lee Day to celebrate his birthday. Museums dedicated to Confederate history were created in Columbia, South Carolina and Richmond, Virginia. The most profound change came in the form of hundreds of public monuments to the Confederate dead. This change in public memorials is largely attributed to the work of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). The UDC was a more national organization than the older Ladies’ Memorial Associations. The UDC spearheaded efforts to venerate the Confederacy and teach the message of the Lost Cause. [8] Historians note that, by the early twentieth century, Southern white women were the strongest voice in perpetuating Lost Cause memory. They used their public platform to praise their parents’ Confederate devotion while teaching social and racist values to the next generation. [9] Between 1895 and the 1920s, the UDC raised dozens of Confederate monuments across the South. Lee was often highlighted in these monuments, whether in statues or in the inscriptions. Children often participated in the unveiling celebrations. Scholars argue that these monuments were visible reminders of a pro-Confederate, Southern identity and of the Jim Crow South society in which Black citizens were considered second class. [10] They also served as mourning objects for the families and communities who had lost loved ones in the Civil War. The UDC monuments were also innovative in how public they were. They were not just memorials to the fallen but visible reminders for later generations. In addition to the numerous cemetery monuments of the Ladies’ Memorial Associations, these new monuments were placed in courthouse squares, on the grounds of state houses, and in urban parks. [11] The most ambitious UDC monument took shape in Georgia. A local chapter led efforts to turn Stone Mountain into a “shrine to the South.” The re-established Ku Klux Klan (KKK) had also chosen the mountain as the location of their first ritual. The landowners, KKK, and UDC were committed to making the mountain a Southern, Lost Cause memorial. Robert E. Lee was the central figure carved into the granite mountain. [12] Lee’s Transformation into a National FigureWhile the UDC led this new generation of Lost Cause memorialists, a younger generation of white male politicians and businessmen, North and South, were spreading a Reconciliationist memory of the Civil War. Many Reconciliationists hoped to rebind the nation’s wounds, and boost economic development, by ignoring the causes of conflict and instead memorializing the valor of the common soldier. In 1887, an Indiana Governor announced that, “The issues upon which that unfortunate struggle were based are buried.” [13] At the fiftieth anniversary of Gettysburg, President Woodrow Wilson stated, “the quarrel forgotten, except that we shall not forget the splendid valor, the manly devotion of the men then arrayed against one another.” [14] Reconciliation events were often highly publicized. Blue-Grey reunions at battle anniversaries brought former enemies together. Reconciliationists even allowed the creation of a Confederate section and Lost Cause-inspired Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery. Some Confederate biographers used the Reconciliationist movement to transform Robert E. Lee into a national figure. A northern paper remarked that “the Lee Cult is much in vogue, even at the North, in these days.” [15] This new generation of writers celebrated Lee’s military skills while avoiding Early’s descriptions of Lee’s invincibility and undying commitment to the Southern Cause. These writers focused on his personal virtues and his post-war success as a college president. Most importantly, they touted Lee’s love of the Union and his efforts at healing the country after the war. [16] Lee’s transformation into a national figure was evident in a variety of memorials. The U.S. Army established Camp Lee in Virginia in 1917 as part of an effort to gain local support for new military bases in the South during World War I. In 1923, the Robert E. Lee Memorial Highway, from Washington, D.C. to San Diego, became the first southern transcontinental highway, a sister highway to the northern route named after Abraham Lincoln.

Library of Congress Union Veterans Challenge Lost Cause Veneration of Lee at Arlington HouseA variety of communities challenged the Reconciliationist movement. Many Union soldiers never forgot that “we fought for Union and liberty [and] they fought for disunion and slavery.” Southern veterans also refused to accept full reconciliation if it meant that the Southern cause was considered wrong. [17] UDC members also complained that young Southern men were forgetting the sacrifices of the Confederate generation in exchange for business opportunities. Former abolitionists, like Frederick Douglass, feared that Northern Reconciliationists erased the promise of emancipation and racial equality from Civil War memory. The debate over Arlington House became an example of the widespread contest over Civil War memory. In the 1920s, Southern women’s groups sought to restore the house and ownership of the property transferred to the UDC. Proponents used Reconciliationist language: “Whatever our opinions and traditions may be…we all realize now that Robert E. Lee was one of the greatest generals and one of the noblest men who ever lived.” [18] The UDC also used the nostalgia of the Lost Cause to promote the house as “an example of the old home of the Southern gentleman and a memorial of the then owner.” [19] Union veterans’ groups, like the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) fought against the effort to have the UDC take ownership of the site. They feared the UDC would turn the house into a Lost Cause shrine to Lee. In 1925, Congress passed legislation to restore the Arlington House. But the Army avoided controversy by focusing interpretation on the Custis Family and George Washington rather than Lee. [20] The legislation protecting Arlington House continued to change after the 1920s. From the time the site was transferred to the National Park Service in 1933 to the most recent legislative change in 1972, these updates often reflected changes in mainstream culture and new academic research. Robert E. Lee in Twentieth Century Popular CultureIn the 1930s, nostalgia for the Old South and Lost Cause took over white popular culture. The Oscar-winning film, Gone with the Wind, invoked a chivalric South. Lee’s position as a national figure also became established with the Pulitzer-prize winning biography written by Douglass Freeman. Freeman merged many of the Lost Cause and reconciliationist motifs and shaped the twentieth century image of Lee. Freeman presented Lee as an invincible general and morally superior figure whose life was paced by a firm sense of duty. A reluctant secessionist, he only suffered defeat because of overwhelming odds. [21] In the 1950s, federal legislation formally adopted this national vision of Lee in the site interpretation. The National Park Service began to emphasize the Reconciliationist and Freeman interpretation of Lee’s military genius and post-war efforts at reuniting the nation. Symbolically, the legislation was enacted on the ninetieth anniversary of the surrender at Appomattox. Legislation in 1972 further solidified this new focus on Lee by changing the site name from the Custis-Lee Mansion to “Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial.” Following the Civil Rights movement, more Civil War historians began to challenge the Lost Cause memory. Lee biographers have begun to question how Lee became a “Marble Man,” and idealized southern planter and Confederate soldier by exploring a more complex portrayal of his life. Researchers have challenged Lost Cause ideas of slavery as humane and enslaved people as happy. Interpreters at antebellum historical sites homes are now exploring the life experience of those who were enslaved. In recent years, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial has adopted this more wholistic understanding of the plantation community and of Robert E. Lee. Exhibits now include significant research and interpretation into the life of enslaved inhabitants, Lee’s views on slavery and Reconstruction, Civil War memory, and the plantation created by the Custis family. Today the National Park Service continues to interpret the history and evolving meaning of Robert E. Lee. Notes [1] Republican Vindicator, (Staunton, VA) September 3, 1869 [2] Robert E. Lee to Thomas L. Rosser, Dec. 13, 1866. Lee Papers, University of Virginia Archives. [3] Gary W. Gallagher, Lee and His Generals in War and Memory (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998), 261. [4] David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), Chapter 8. [5] Jubal Early, “1872 Birthday oration,” in William Jones, Personal Reminiscences of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Forge, 2003), 42. [6] Thomas L. Connelly, The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977) 27. [7] Connelly, Marble Man, 156-8. [8] Janney, Remembering the Civil War, 180. [9] Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 32. [10] Cox, Dixie’s Daughters,xxii. [11] John J. Winberry, “’Lest We Forget’: The Confederate Monument and the Southern Townscape,” reprinted in Southeastern Geographer, vol. 55. No 1 (2015), 20. [12] David B. Freeman, Carved in Stone: The History of Stone Mountain (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1997), 57. [13] "Feds and Confeds Fraternizing,” Portage (WI) Daily Register, September 22, 1887. [14] Woodrow Wilson, July 4, 1913. Address at Gettysburg [15] "The Worship of Lee,” The Minneapolis Tribune, May 30, 1890, pg. 4. [16] Connelly, Marble Man, 115. [17] Janney, Remembering the Civil War, 9; 103. [18] Michael Chornesky, “Confederate Island upon the Union’s ‘Most Hallowed Ground’: The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921-1937,” Washington History ,vol. 27, no. 1 (Spring 2015), 26. [19] “U.D.C Notes, The Lee Mansion,” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 29 (1921), 350-1. [20] Chornesky, “Confederate Island,” 28. [21] James McPherson, “Foreword,” in Richard Harwell, ed, Lee (New York: Touchstone, 1997). |

Last updated: September 14, 2021