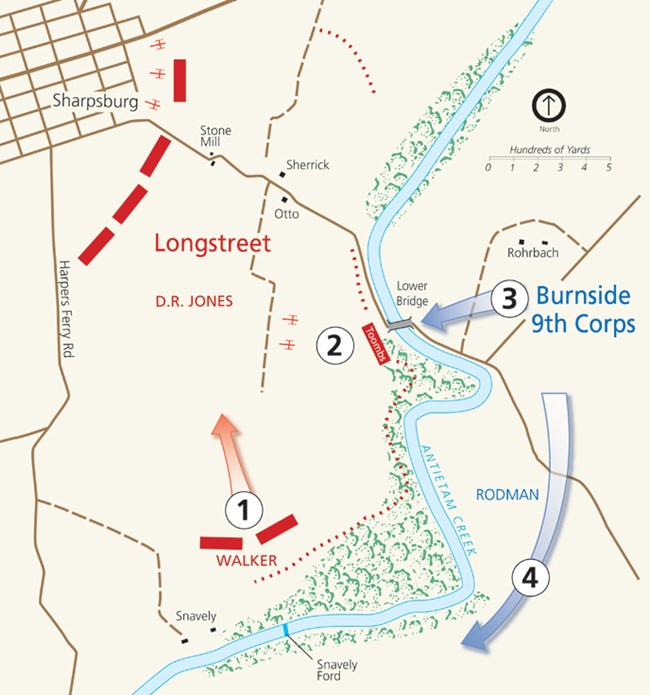

Introduction About 500 Confederate soldiers held the area overlooking the Lower Bridge for three hours. Burnside's command finally captured the bridge and crossed Antietam Creek, which forced the Confederates back toward Sharpsburg. A Crucial Crossing, a General's Namesake, a Battlefield Icon Known at the time of the battle as the Rohrbach or Lower Bridge, this picturesque crossing over Antietam Creek was built in 1836 to connect Sharpsburg with Rohrersville, the next town to the south. It was actively used for traffic until 1966 when a bypass enabled the bridge to be restored to its 1862 appearance. For more than three hours on September 17, 1862, Confederate Gen. Robert Toombs and fewer than 500 Georgia soldiers manned this imposing position against three Federal assaults made by Gen. Ambrose Burnside's much larger Ninth Corps. Confederate General James Longstreet wrote of the action: "Gen. Toombs held the bridge and defended it most gallantly, driving back repeated attacks, and only yielded it after the force brought against him became overwhelming and threatened his flank and rear." About 1:00 p.m., with Union soldiers crossing downstream and another attack made on the bridge, Toombs and his men had to retreat. However, the strong delaying action provided much needed time to allow Gen. A.P. Hill's Confederate soldiers, marching from Harpers Ferry, to arrive on the field. "Repulsed Again and Again"

(2) Fewer than 500 Confederate troops, commanded by Gen. Robert Toombs, lined Antietam Creek from this point southward to Snavely Ford. Col. Henry Benning commanded the men that were here guarding the bridge. A Union soldier, who attempted to cross the span, remembered that the Confederates "were snugly ensconced in their rude but substantial breastworks, in quarry holes, behind high ranks of cordwood, logs, stone piles, etc." (3) At about 9:30 a.m., the first of three major Federal assaults to take the bridge moved forward. The first attack, Toombs reported, "was repulsed with great slaughter and at regular intervals… other attempts of the same kind, all of which were gallantly met and successfully repulsed…" After defending the area for over three hours, the Confederates began to run low on ammunition. (4) A Union division, commanded by Gen. Isaac P. Rodman, moved downstream in an attempt to ford the Antietam. The combination of Rodman's troops crossing Snavely Ford on their flank, depleted ammunition, and a third Federal assault toward the bridge, eventually forced Toomb's men from their overlook. At about 1:00 p.m. the Confederates pulled back toward the Harpers Ferry Road to await the final Union attack. TranscriptHello, I'm Park Ranger Jess Rowley and I'm standing at tour stop #8 the Burnside bridge, one of three bridges used during the battle. This is the only bridge that Confederate General Robert E Lee chose to defend with troops. The importance of this bridge lay in the strength of it as a defensive position, its location within the overall Confederate army, and its proximity to a Ford. The only forward that the Confederate Army would need to use if forced to withdraw. As the fighting raged to the north of us, as discussed in the first seven stops, a separate union effort went on here, an effort to turn the right or southern end of the Confederate Army and perhaps cut them off from the safety of Virginia. Known as the Rohrbach Bridge before the Battle of Antietam, the Burnside Bridge was built in 1836 at a cost of $3200. Named after the closest farmstead to the bridge, it connected the town of Sharpsburg with the town of Morrisville, a small community to the South. After viewing the natural strength of his position along the Antietam Creek, Confederate General Robert E Lee chose to anchor the right end of his army here. Lee realized that the waist deep Antietam was not easily crossed and the name Antietam actually means swift flowing waters. This swift Creek behind me hides a slippery bottom, and as you can see, has carved a steep bank along most of its length. Union soldiers wearing full wool uniforms and shoes with no tread, wrists slipping if they entered the water and drenching themselves and their black powder, which would make their weapons useless. As such, the bridges along the Antietam were indispensable. The Confederate side of the bridge was a naturally strong position with 80-foot Bluffs overlooking the 12-foot-wide bridge hidden by trees and underbrush. Southern defenders would have a clear field of fire with the open grassy floodplain of the Antietam Creek offering attacking soldiers little in the way of cover. The bridge did present one potential weakness for Lee's army. If captured, it offered Union troops the fastest route to pack horse forward. The only forward Lee's army could use if forced to withdraw. Lee initially placed roughly 7000 soldiers in the vicinity of the bridge. However, by 9:00 AM, Lee had ordered nearly 4000. Troops from the right or south side of his line, sending them north to help against the morning assault. This left only the 3000 men of Confederate General David R Jones division to cover the entire southern half of the battle line. Jones assigned the 500 men of Confederate General Robert Toombs's brigade to guard the critical crossing point. The Union plan of attack had called for a coordinated effort against both ends of the Confederate Army. While troops under Joseph Hooker and Joseph Mansfield attacked from the north, Union General Ambrose Burnside was assigned the duty of launching the Union assault on this end of the line with his 9th Corps numbering nearly 13,000 men, the 9th core was a recent fusion of several commands. But its foundation was a strong group of veteran soldiers and officers that had seen action and success along the North Carolina coast over the past year. Burnside, recognizing the strength of the Confederate position guarding the bridge, initially called for a flanking maneuver designed to use a downstream forward known as navies forward to flank the bridge and save Union. Lives this 3000-man force, led by Union General Isaac Peace Rodman would be plagued by mishaps, poor maps, and impossible terrain, and as a result would not get into position until afternoon. As such, a little before 10:00 AM with pressure coming from headquarters to join the battle, Burnside would begin his frontal assaults on the bridge. Union Colonel Henry Kingsbury, brother-in-law of Confederate general David R Jones, whose troops he was destined to attack, would lead the first assault at the head of his 450 Man, 11 Connecticut. Kingsbury and his men quickly ran into a wall of fire, and within 30 minutes their assault had been repulsed and 1/3 of their regiment lay dead or wounded, including Colonel Kingsbury, whose body had been pierced by no fewer than four enemy bullets, killed by his brother-in-law soldiers. Next would be Union General George Crook's Brigade. Crooks assault moved forward a little before 11, but his brigade suffered from a lack of knowledge of the ground they would need to crossover to attack one of crooked regiments remained in reserve, never joining in the attack, while his other two attempted piece meal assaults that appeared like several small disjointed attacks to the Confederate defenders. Of course it did not help crooked effort that Confederate Colonel Henry Benning reported each union assault quote was met by our rapid, well directed and unflinching fire from our men under which the enemy, after a vain struggle, broke and fell back. But a vision of Union General Samuel D Sturgis was assigned around 11:30 to lead the next attack. He immediately ordered Union General James Nagles brigade to advance with his 48th Pennsylvania, laying down a covering fire. Nagle ordered the second Maryland to lead the way, followed by the 6th and 9th New Hampshire Regiments. The second Maryland quickly lost 40% of their soldiers. The six New Hampshire came up only to endure a similar slaughter. Major Lyman Jackman of that regiment noted that quote with fixed bayonets at the double quick, our men passed through a narrow opening and a strong chestnut fence. They charge in a most gallant manner, directly up the road to the bridge of the first hundred men who pass through the opening of the fence. At least nine tents were either killed or wounded, such sweeping destruction. Check the advancing column. The 9th New Hampshire. Seeing the futility of such an assault pulled back to avoid meeting the same right. With the repulse of Nagle, Sturgis now ordered Union General Edward Ferraro's brigade forward. The time was 12 and Toombs' Georgians had endured 3 assaults over 2 hours, and his men and ammunition were becoming exhausted. Ferraro selected the 51st Pennsylvania and the 51st New York, known as the Twin 51st, to lead the assault. These men, about to lead the 4th assault on the seemingly impregnable Confederate position, asked for some added motivation, whiskey rations that had withheld. Ferraro promised that should they carry the position, he would provide them with their whiskey, even if he had to pay for it himself. With this added motivation and the covering fire from Union cannon and several 100 union soldiers left from the previous assaults, Ferraro's twin 51st launched their attack. Initial Confederate fire halted this newest union assault, but adding to Tombs' desperation was news that Isaac Rodman, that long-awaited flanking force sent by Burnside, had found and begun to cross Navy's. With their flank turn and ammunition withering away, Toombs's Georgians began to fall back in twos and threes. At this moment, the soldiers from Pennsylvania and New York huddled behind a stone wall and opposed and rail fence at the mouth of the bridge joined together for the final push. This was the Georgians queue and they fled as Union troops poured across. Burnside had finally captured the bridge that would forever bear his name. Now began the process of marching men over the bridge to link up with Rodman's division for what would become the final attack of the Union Army. The fight for this bridge had resulted in 600 casualties, with nearly 500 union and over 100 Confederate troops being killed or wounded in the fight for this vital stone structure. Compared to the slaughter of the cornfield or bloody lane, the fight here may feel small, however, for the men from both sides, who were often only separated by the 20-yard wide. Grand Teton Creek the deeply personal struggle for this bridge was unsurpassed in acts of desperation, valor, ferociousness, and hero. The bloody struggle over the bridge had ended, but the fight for the bridge was far from over. The fight to preserve the bridge has included stopping vehicle traffic in the 1960s and a complete rehabilitation of the bridge beginning in 2015. This project, initiated for a large section of the bridge, fell into the Antietam Creek in January 2014. Included a complete scanning of the bridge to map the location of each stone and then a breaking down and rebuilding of the bridge piece by piece, with each Dome placed back in its historical local. The bridge stands today as a testament to the valor of the men who fought for its control on September 17th, 1862, as a preservation victory, that we can all see and appreciate and as a tangible piece of our shared history, that will remain for future generations. Join us at the next Stop tour. Stop #9 the final attack as we discussed, the final actions of the Battle of Antietam.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Burnside Bridge Tour Stop 8 Go to the next tour stop - The Final Attack |

Last updated: April 17, 2023