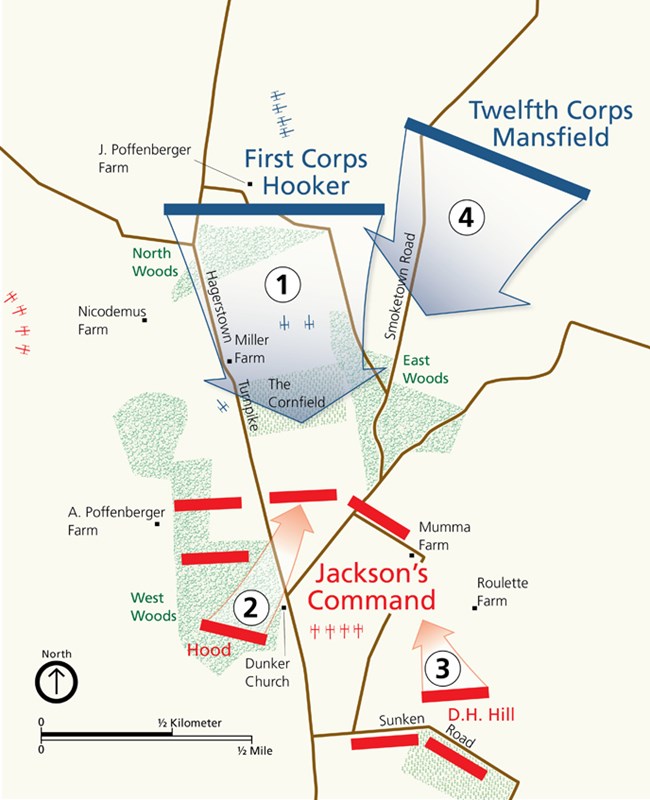

Introduction This 24-acre cornfield, owned by D.R. Miller, saw some of U.S. history's most horrific fighting. For nearly three hours, Hooker and Mansfield's Union forces battled Jackson's Confederates. Many regiments on both sides were cut to pieces. Hays' Louisiana Brigade suffered over 60-percent casualties in 30 minutes. The Most Terrible Clash of Arms As Union soldiers stepped out of the Cornfield at dawn, September 17, 1862, Confederate troops unleashed a horrific volley. The single, bloodiest day in American History had begun in earnest. For the next four hours the Cornfield was the center of a storm of lead, iron, and flame as Federal soldiers from the First and Twelfth Corps clashed with Lee's men. The Cornfield changed hands again and again as both sides attacked and counterattacked. One soldier remembered: "The air seems full of leaden missiles. Rifles are shot to pieces in the hands of soldiers, canteens and haversacks are riddled with bullets, the dead and wounded go down in scores." More than 25,000 soldiers fought in and around the Cornfield. By 9:30 a.m. thousands of them lay dead and dying. Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood wrote: "It was here that I witnessed the most terrible clash of arms, by far, that has occurred during the war." Union Gen. Joseph Hooker remembered that "every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield." A Cornfield Unlike Any Other "Through a shower of bullets and shells, it was only the thoughts of home that brought me from that place." Pvt. James Dougherty, 128th Pennsylvania Infantry, wounded in the Cornfield

(2) At 7:00 a.m., Gen. John Bell Hood’s Confederate Division of approximately 2,000 men was waiting behind the Dunker Church. Jackson called them into battle and, “In less than five minutes we were advancing toward the enemy. In less than fifteen we were sending and receiving death missiles by the bushel.” Hood’s men drove north, forcing the First Corps back across the Cornfield. (4) At 8:00 a.m., Gen. Joseph Mansfield’s Twelfth Corps, over 7,000 soldiers, arrived and drove back Hood’s men and the Confederate reinforcements from the Sunken Road. Gen. Mansfield was mortally wounded and Gen. Alpheus Williams took command of the Corps. At about 9:00 a.m. there was a short lull in the action. Most of the Confederates on the north end of the battlefield retreated to the West Woods and almost 8,000 Union and Confederate soldiers had been killed or wounded in and around the Cornfield. TranscriptHello, I'm Park Ranger Brian Baracz and I'm standing at tour stop #4 the cornfield. During the first three hours of battle, Union and Confederate forces engaged in vicious combat for control of D.R. Miller's 30-acre cornfield. When all was said and done, the cornfield had changed hands no less than 6 times. 6000 soldiers had been killed or wounded. In 1/2-mile radius of where I'm now standing. Following a short skirmish on the evening of September 16 for control of the East Woods Tour stop, #3 soldiers North and South slept on their arms during a misty and rainy night. No campfires were permitted due to the close proximity of the opposing sides. North of the cornfield in and around the North Woods Tour, stop #2 the troops of the Union First Corps and the 12th Corps, commanded by General Joseph Hooker and General Joseph Mansfield, numbering around 18,000 men, struggled to get a restful night of sleep. While South of the cornfield in the West Woods around the Mumma Farm and behind the Dunker Church were posted just under 10,000 Confederates under command of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson before the Sun rose over South Mountain on the morning of September 17th, 1862, soldiers of both sides remembered a dense fog covered the fields. It was in these minutes before the sun rose at the first shots of the battle were fired, a scattering of infantry fire from around the Mumma Farm tore stop number six and Confederate artillery fire opened in what is still today the single bloodiest day in American history. The first Union soldiers to move South out of the north woods towards the cornfield were men from General James Ricketts division. 1300 men, commanded by General Abram Duryee, advanced through Miller's cornfield a little before 6:00 AM, just as they reached the South edge of the cornfield. Troops from Georgia, commanded by Colonel Marcellus Douglas, unleashed a tremendous volley. Over the course of the next 30 minutes, the two sides struggled to gain the upper hand and eventually neither side would. Deryk’s men gradually fell back, having lost 33% in 30 minutes after Confederate reinforcements moved in to support Douglas. Over the next three hours, control of the cornfield changed hands over six times. The casualties piled up. Union troops from General Abner Doubleday's division were the next to move into the corn. Eventually, these men from Wisconsin and Indiana, commanded by General John Gibbon, were able to drive the Confederates back down the Hagerstown Turnpike and towards towards stop #1 the Dunker Church. In this action, Gibbon assisted the artilleryman of Battery B 4th the United States Artillery in Loden and firing the gun. An observer remembered that Gibbon helped to load and site the cannon. During the same action, the battery Bugler Johnny Cook was awarded the medal of honor for helping to load and fire the peace. He’s believed to be the youngest to be presented our nation's highest military honor. A federal soldier wrote of the fighting, “A long line of butternut and Grey rose up from the ground. Simultaneously, the hostile battle lines opened to terrible fire. There was on the part of our men the intense, hysterical, excitement, eagerness to go forward, reckless disregard of life, of suffering, of everything but victory. Men and officers of New York and Wisconsin are fused into a common mass in the frantic struggle to shoot fast. Men are falling in their places or running back into the corn. Many of the recruits who are killed or wounded only left home 10 days ago.” At approximately 7:00 AM, it appeared that the federal troops were about to capitalize on General George Mcclellan's battle plan, hit the flanks, and then deliver a strike in the middle of Lee's line, cutting the Confederate army into two pieces. A Confederate counterattack stifled those plans. Men commanded by General John Bell Hood advanced out of the woods from around the Dunker Church and drove the Union troops back northward. The Southern troops pushed the men and blew back towards the east woods and into the cornfield, and again this famous piece of ground changed hands around this time the fighting was very confusing. The fog, the smoke of battle, that confusion and disorientation created by woodlots, cornfields, and fence lines, and the loss of generals commanding men caused confusion on both sides. Hooker’s First Corps was spent and the Unit 12 Corps, commanded by General Joseph Mansfield, moved to strengthen the federal line. Hood’s men had just been driven back as well as troops from General DH Hills division that had been sent to bolster Stonewall Jackson's troops. It was around 8 AM that the men from George Green's division, the 12th court, drove the Confederates from the cornfield for the last time that bloody morning. Finally, at about 9:00 AM, a lull fell over the cornfield. The official report of Confederate Jubal Early provides us with some insight of the casualties sustained. He wrote, “Lawton's brigade lost 554 killed and wounded out of 11150, losing 5 regimental commanders out of 6. Hayes's brigade sustained a loss of 323 out of 550, including every regimental commander and all of his staff. And Colonel Walker, in one of his staff, disabled the brigade he was commanding, had sustained the loss of 228 out of less than 700 present, including three out of four regimental commanders.” In the days following the battle. Alexander Gardner, who was an assistant to Matthew Brady, arrived in the battlefield. He captured the first images of dead soldiers in the battlefield viewed by the American public. During his trip to Antietam, he took many images on the northern end of the battlefield. One of his photos that looks N along the Hagerstown Turnpike reveals the horrors of the bloody day. This image was taken about 100 yards to the southwest of the Cornfield and shows Confederate troops that have been killed in their fighting along the Pike. Union soldier Rufus Laws wrote of this section of the field after the war, “The piles of dead in the Sharpsburg and Hagerstown Turnpike surpassed anything and any other battlefield of my observation. The angle of death at Spotsylvania, the Cold Harbor slaughter pen, the Fredericksburg Stonewall. We're all mentally compared by me. And my feeling was that the Antietam Turnpike surpassed all and manifest evidence of slaughter.” The next major engagement started to unfold at about 9:15 in the morning as Union soldiers from the Second Corps, commanded by Edwin Sumner, made their way towards the West Woods. Make sure to watch our next video tour stop #5 the West Woods to learn about the action that unfolded on that part of the battlefield.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

A short video presentation on Tour Stop 4, The Cornfield. Go to the next tour stop - the West Woods |

Last updated: September 15, 2020