| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

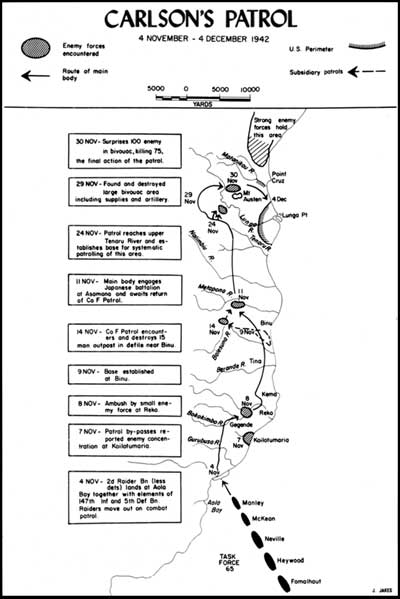

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR The Long Patrol Not long after the departure of the 1st Raiders, it was the turn of the 2d Raiders to fight on Guadalcanal. Carlson's outfit had been refitting in Hawaii after the Midway and Makin battles. In early September the unit boarded a transport for Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, the primary staging area for most reinforcements going to the southern Solomons. There they continued training until Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (Commander, Amphibious Force, South Pacific) decided to land a force at Aola Bay on the northeast coast of Guadalcanal to build another airfield. He assigned Carlson and two companies of raiders to secure the beachhead for an Army battalion, Seabees, and a Marine defense battalion. The McKean and Manley placed Companies C and E ashore on the morning of 4 November. There was no opposition, though it soon became apparent the swampy jungle was no place to put an airfield. On 5 November Vandegrift sent a message to Carlson by airdrop. Army and Marine elements were moving east from the perimeter to mop up a large force of Japanese located near the Metapona River. This enemy unit, the 230th Infantry Regiment, had cut its way through the jungle from the west as part of a late-October attack on Edson's Ridge by the Sendai Division. For various reasons, the 230th had failed to participate in the attack, and then had completed a circumnavigation of the Marine perimeter to reach its current location in the east. The Tokyo Express had recently reinforced it with a battalion of the 228th Infantry. Vandegrift wanted the raiders to march from Aola and harass the Japanese from the rear. Carlson set out with his force on 6 November, with a coastwatcher and several native scouts as guides. Among the islanders was Sergeant Major Jacob Vouza, already a hero in the campaign. The men initially carried four days of canned rations.

The raiders moved inland before heading west. The trails were narrow and overgrown, but the native scouts proved invaluable in leading the way. On 8 November the point ran into a small Japanese ambush near Reko. The Marines killed two Japanese; one native suffered wounds. The next day the column reached Binu, a village on the Balesuna River eight miles from the coast. There Carlson halted while his patrols made contact with Marine and Army units closing in on the main Japanese force. On 10 November Companies B, D, and F of the 2d Raiders landed at Tasimboko and moved overland to join up with their commander. (Company D was only a platoon at this point, since Carlson had used most of its man power to fill out the remaining companies prior to departing Espiritu Santo.) From that point on the raiders also received periodic resupplies, usually via native porters dropped on the coast by Higgins boats. Rations were generally tea, rice, raisins, and bacon — the type of portable guerrilla food Carlson thrived on — reinforced by an occasional D-ration chocolate bar. On the nights of 9 and 10 November about 3,000 Japanese escaped from the American ring encircling them on the Metapona. They were hungry and tired, and probably dispirited now that they had orders to retrace their steps back to the western side of the perimeter. But they were still a formidable force. On the 11th the 2d Raiders had four companies out on independent patrols while the fifth guarded the base camp at Binu. Each unit had a TBX radio. At mid-morning one outfit made contact with a patrol from 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and learned of the enemy breakout. A few minutes later Company C ran into a large force of Japanese near Asamama on the Metapona River. The Marines had been crossing a wide grassy area. When the advance guard entered a wooded area on the opposite side it surprised the enemy in their bivouac. In the initial action, the advance guard inflicted significant casualties on the Japanese, but lost five men killed and three wounded. In short order the enemy had the remainder of the company pinned down in the open with rifle, machine gun, and mortar fire.

Carlson vectored two of his patrols in that direction to assist, and dispatched one platoon from the base camp. As it crossed the Metapona to reach the main battle, Company E tangled with another enemy group coming in the opposite direction. The more numerous Japanese initially forced the Marines to withdraw, but Major Richard T. Washburn reorganized his company and counterattacked the enemy as they attempted to cross the river. The raiders inflicted significant casualties on their opponent, but could not push through to link up with Charlie Company. In mid-afternoon, Carlson himself led Company F toward Asamama. By the time he arrived, Company C had extricated itself under covering fire from its own 60mm mortars. Carlson called in two dive bombers on the enemy, ordered Company E to break off its independent action, and launched Company F in a flanking attack against the main Japanese force. Those raiders completed the maneuver by dusk, only to find the enemy position abandoned. The battalion assembled back at Binu that night. There Company D reported that it had run into yet another group of enemy and been pinned down for most of the afternoon. The understrength unit had lost two killed and one wounded.

On 12 November Carlson led Companies B and E back to the woods at Asamama. Throughout the day enemy messengers attempted to enter the bivouac site under the mistaken notion that it still belonged to their side; the raiders killed 25 of them. In the afternoon Carlson ordered Company C to join him there. The next day he observed enemy units moving in the vicinity, and he placed artillery and mortar fire on five separate groups. After each such mission the raiders dealt with Japanese survivors trying to make their way into the woods. On 14 November Carlson decided to pull back to Binu. That same day a Company F patrol wiped out a 15-man enemy outpost that had been reported by native scouts. After a brief period to rest and replenish at Binu, the 2d Raiders moved their base camp to Asamama on 15 November. During two days of patrolling from that site, Carlson determined that the main enemy force had departed the area. At Vandegrift's request, the raider commander entered the perimeter on 17 November. Vandegrift directed Carlson to search for "Pistol Pete," an enemy artillery piece that regularly shelled the airfield. The battalion also was to seek out trails circling the perimeter, and any Japanese units operating to the south. The raiders moved forward to the Tenaru River over the next few days. On 25 November Company A arrived from Espiritu Santo and joined the battalion. For the next few days the 2d Raiders divided into three combat teams of two companies apiece, with each operating from its own patrol base. Each day they moved farther into the interior of the island, in the area between the headwaters of the Tenaru and Lunga rivers. Carlson remained with the center team, from which point he could quickly reinforce either of the flank detachments. On 30 November the battalion crossed over the steep ridgeline that divided the valleys of the Tenaru and Lunga. Discovery of a telephone wire led the raiders to a large bivouac site, which held an unattended 75mm mountain gun and a 37mm antitank gun. Marines removed key parts of the weapons and scattered them down the hillside. Farther on the advance guard entered yet another bivouac site, this one occupied by 100 Japanese. Both sides were equally surprised, but Corporal John Yancey charged into the group firing his automatic weapon and calling for his squad to follow. The more numerous enemy were at a disadvantage since their arms were stacked out of reach. The handful of raiders routed the Japanese and killed 75. Carlson called it "the most spectacular of any of our engagements." For this feat Yancey earned the first of his two Navy Crosses (the second came years later in Korea). The next day, 1 December, a Douglas R4D Skytrain transport air dropped badly needed rations, as well as orders for the battalion to enter the perimeter. Carlson asked for a few more days in the field and got it. On 3 December he held a "Gung Ho" meeting to motivate his exhausted men for one more effort. Then he divided the 2d Raiders in half, sending the companies with the most field time down to Marine lines. The rest he led up to the top of Mount Austen, where a raider patrol had discovered a strong but abandoned Japanese position. The force had barely reached their objective when they encountered an enemy platoon approaching from a different direction. After a two-hour fire fight and two attempts at a double envelopment, the Marines finally wiped out their opponents. The result was 25 enemy dead at a cost of four wounded Marines (one of whom died soon after). The raiders spent a tough night on the mountain, since there was no water available and their canteens were empty. The next day Carlson led the force down into the Marine perimeter, but not without one last skirmish. Seven Japanese ambushed the point and succeeded in killing four men before the raiders wiped them out. The long patrol of the 2d Raiders was extremely successful from a tactical point of view. The battalion had killed 488 enemy soldiers at a cost of 16 dead and 18 wounded. Carlson's subsequent report praised his guerrilla tactics, which undoubtedly played an important role in the favorable exchange ratio. Far away from the Marine perimeter, the Japanese became careless and allowed themselves to be surprised on a regular basis, a phenomenon other Marine units had exploited earlier in the campaign. Since the 2d Raiders operated exclusively in the enemy rear, they reaped the benefit of their own stealthiness and this Japanese weakness. The stated casualty figures, however, did not reflect the true cost to the Marines. During the course of the operation, the 2d Raiders had evacuated 225 men to the rear due to severe illness, primarily malaria, dysentery, and ringworm. Although sickness was common on Guadalcanal, Carlson's men became disabled at an astonishing rate due to inadequate rations and the rough conditions, factors that had diminished significantly by that point in the campaign for other American units. Since only two raider companies had spent the entire month in combat, the effect was actually worse than those numbers indicated. Companies C and F had landed at Aola Bay with 133 officers and men each. They entered the perimeter on 4 December with a combined total of 57 Marines, barely one-fifth their original strength. Things would have been worse, except for the efforts of native carriers to keep the raiders supplied. Guerrilla tactics inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, but at an equally high cost in friendly manpower. Nevertheless, the 2d Raiders could hold their heads high. Vandegrift cited them for "the consumate skill displayed in the conduct of operations, for the training, stamina and fortitude displayed by all members of the battalion, and for its commendable aggressive spirit and high morale."

|