| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR Edson's Ridge The next day Red Mike discussed the situation with division planners. Intelligence officers translating the captured documents confirmed that 3,000 Japanese were cutting their way through the jungle southwest of Tasimboko. Edson was convinced that they planned to attack the currently unguarded southern portion of the perimeter. From an aerial photograph he picked out a grass-covered ridge that pointed like a knife at the airfield. His hunch was based on his own experience in jungle fighting and with the Japanese. He knew they liked to attack at night, and that was also the only time they could get fire support from the sea. And a night attack in the jungle only had a chance if it moved along a well-defined avenue of approach. The ridge was the obvious choice. Thomas agreed. Vandegrift did not, but they convinced the general to let the raiders and parachutists shift their bivouac to the ridge in order to get out of the pattern of bombs falling around the airfield. The men moved to the new location on 10 September. Contrary to their hopes, it was not a rest zone. Japanese planes bombed the ridge on the 11th and 12th. Native scouts brought reports of the approaching enemy column, and raider patrols soon made contact with the advance elements of the force. The Marines worked to improve their position under severe handicaps. There was very little barbed wire and no sandbags or engineering tools. Troops on the ridge itself could not dig far before striking coral; those on either flank were hampered by thick jungle that would conceal the movement of the enemy. Casualties had thinned ranks, while illness and a lack of good food had sapped the strength of those still on the lines.

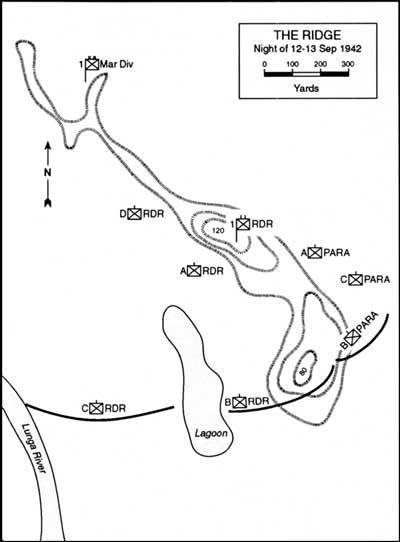

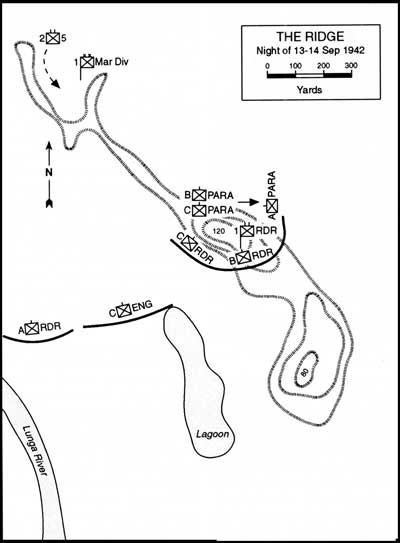

Edson and Thomas did the best they could with the resources available. Red Mike used the spine of the ridge as the dividing point between his two rump battalions. One company of parachutists held the left of his line, with the rest of their comrades echeloned to the rear to protect that flank. Two companies of raiders occupied the right, with that flank anchored on the Lunga River. A lagoon separated the two raider units. Edson attached the machine guns to the forward companies and kept the remaining raiders in reserve. (Company D was no larger than a platoon now, since Red Mike had used much of its manpower to fill holes in the other three rifle companies.) He set up his forward command post on Hill 120, just a few hundred yards behind the front lines. Thomas placed the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, in reserve between the ridge and the airfield. Artillery forward observers joined Edson and registered the howitzers. The Marines were as ready as they could be, but the selection of the ridge as the heart of the defense was a gamble. To the west of the Lunga there were only a few strongpoints occupied by the men from the pioneer and amphibious tractor battalions. To the east of Red Mike's line there was nothing but a mile of empty jungle. Kawaguchi was having his own problems. In addition to the setback at Tasimboko, his troops were having a tough time cutting their way through the heavy jungle and toiling over the many ridges in their path. Some of his difficulties were self-inflicted. His decision to attack from the south had required him to leave his artillery and most of his supplies behind, since they could not be hauled over the rough jungle trail. Thus he would go into battle with little fire support and poor logistics. He then detailed one of his four battalions to make a diversionary attack along the Tenaru. This left him with just 2,500 men for the main assault. Finally, he had underestimated the time needed to reach his objective. On the evening of 12 September, as the appointed hour for the attack approached, Kawaguchi realized that only one battalion had reached its assigned jumpoff point, and no units had been able to reconnoiter the area of the ridge. He wanted to delay the attack, but communications failed and he could not pass the order. Behind schedule and without guides, the battalions hastily blundered forward, only to break up into small groups as the men fought their way through the tangled growth in total darkness. At 2200 a Japanese plane dropped a series of green flares over the Marine perimeter. Then a cruiser and three destroyers opened up on the ridge. For the next 20 minutes they poured shells in that direction, though most rounds sailed over the high ground to land in the jungle beyond, some to explode among the Japanese infantry. When the bombardment ceased, Kawaguchi's units launched their own flares and the first piecemeal attacks began. The initial assault concentrated in the low ground around the lagoon. This may have been an attempt to find the American flank, or the result of lack of familiarity with the terrain. In any case, the thick jungle offset the Marine advantage in firepower, and the Japanese found plenty of room to infiltrate between platoon strongpoints. They soon isolated the three platoons of Company C, each of which subsequently made its way to the rear. The Marines on the ridge remained comparatively untouched. As daylight approached the Japanese broke off the action, but retained possession of Company C's former positions. Kawaguchi's officers began the slow process of regrouping their units, now scattered over the jungle and totally disoriented. In the morning Edson ordered a counterattack by his reserve companies. They made little headway against the more-numerous Japanese, and Red Mike recalled them. Since he could not restore an unbroken front, he decided to withdraw the entire line to the reserve position. This had the added benefit of forcing the enemy to cross more open ground on the ridge before reaching Marine fighting holes. In the late afternoon the B Companies of both raiders and parachutists pulled back and anchored themselves on the ridge mid-way between Hills 80 and 120. Thomas provided an engineer company, which Edson inserted on the right of the ridge. Company A of the raiders covered the remaining distance between the engineers and the Lunga. The other two parachute companies withdrew slightly and bulked up the shoulder of the left flank. The remains of Companies C and D assumed a new reserve position on the west slope of the ridge, just behind Hill 120. Red Mike's command post stayed in its previous location. The Japanese made good use of the daylight hours and prepared for a fresh effort. This time Kawaguchi would not make the mistake of getting bogged down in the jungle; he would follow the tactics Edson had originally expected and concentrate his attack on the open ground of the ridge. The new assault kicked off just after darkness fell. The initial blow struck Company B's right flank near the lagoon. A mad rush of screaming soldiers drove the right half of the raider company out of position and those men fell back to link up with Company C on the ridge. Inexplicably, Kawaguchi did not exploit the gap he had created. Possibly the maneuver had been a diversion to draw Marine reserves off the ridge and out of the way of the main effort.

Edson had to decide quickly whether to plug the hole with his dwindling reserve or risk having the center of his line encircled by the next assault. The enemy soon provided the answer. By 2100 Japanese soldiers were massing around the southern nose of the ridge, making their presence known with the usual barrage of noisy chants. They presumably were going to launch a frontal assault on the center of the Marine line. Red Mike ordered Company C of the raiders and Company A of the parachutists to form a reserve line around the front and sides of Hill 120. Japanese mortar and machine-gun fire swept the ridge; the Marines responded with artillery fire on suspected assembly areas. The assault waves finally surged forward at 2200. The attack, on a front all across the ridge, immediately unhinged the Marine center. As Japanese swarmed toward the left flank of his Company B, Captain Harry L. Torgerson, the parachute battalion executive officer, ordered it to withdraw. The parachutists in Company C soon followed suit. Torgerson gathered these two units in the rear of Company As position on Hill 120, where he attempted to reorganize them. The remaining Company B raiders were now isolated in the center. The situation looked desperate. At this point, the Japanese seemed to take a breather. Heavy fire raked the ridge, but the enemy made no fresh assaults. Edson arranged for more artillery support, and got his own force to provide covering fire for the withdrawal of the exposed raiders of Company B. For a time it looked like the series of rearward movements would degenerate into a rout. As a few men around Hill 120 began to filter to the rear, Red Mike took immediate steps to avert disaster. From his CP, now just a dozen yards behind the front, he made it known that this was to be the final stand. The word went round: "No body moves, just die in your holes." Major Bailey ranged up and down the line raising his voice above the din and breathing fresh nerve into those on the verge of giving up. The commander of the Parachute Battalion broke down; Edson relieved him on the spot and placed Torgerson in charge. The new position was not very strong, just a small horseshoe bent around the hill, with men from several units intermingled on the bare slopes. Red Mike directed the artillery to maintain a continuous barrage close along his front. When the Japanese renewed their attack, each fresh wave of Imperial soldiers boiled out of the jungle into a torrent of steel and lead. In addition to the firepower of artillery and automatic weapons, men on the lines tossed grenade after grenade at whatever shapes or sounds they could discern. Supplies of ammunition dwindled rapidly, and division headquarters pushed forward cases of belted machine gun ammunition and grenades. One of the Japanese assaults, probably avoiding the concentrated fire sweeping the crest, pushed along the jungle edge at the bottom of the slope and threatened to envelop the left flank. Edson ordered Torgerson to launch a counterattack with his two reorganized parachute companies. These Marines advanced, checked the enemy progress, and extended the line to prevent any recurrence. Red Mike later cited this effort as "a decisive factor in our ultimate victory." At 0400 Edson asked Thomas to commit the reserve battalion to bolster his depleted line. A company at a time, the men of the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, filed along the top of the ridge and into place beside those who had survived the long night. By that point the Japanese were largely spent. Kawaguchi sent in two more attacks, but they were hit by artillery fire as the troops assembled and never presented much of a threat. A small band actually made it past the ridge and reached the vicinity of the airfield; the Marines providing security there dealt with them.

The onset of daylight brought an end to any organized effort, though remnants of Japanese assault units were scattered through the fringing jungle to the flanks and rear of the Marine position. Squads began the long process of rooting out these snipers. Edson also ordered up an air attack to strike the enemy units clinging to the southern end of the ridge. A flight of P-400s answered the call and strafed the exposed enemy groups. Kawaguchi admitted failure that afternoon and ordered his tattered brigade to retreat. The raiders and parachutists had already turned over the ridge to other Marines that morning. The 1st Raiders had lost 135 men, the 1st Parachute Battalion another 128. Of those, 59 men were dead or missing-in-action. Seven hundred Japanese bodies littered the battlefield, and few of Kawaguchi's 500 wounded would survive the terrible trek back to the coast. The battle was much more than a tremendous tactical victory for the Marines. Edson and his men had turned back one of the most serious threats the Japanese were to mount against Henderson Field. If the raiders and parachutists had failed, the landing strip would have fallen into enemy hands, and the lack of air cover probably would have led to the defeat of the 1st Marine Division and the loss of Guadalcanal. Such a reversal would have had a grave impact on the course of the war and the future of the Corps. Vandegrift wasted no time in recommending Edson and Bailey for Medals of Honor. Red Mike's citation noted his "marked degree of cool leadership and personal courage." At the height of the battle, with friendly artillery shells landing just 75 yards to the front, and enemy bullets and mortars sweeping the knoll, Edson had never taken cover. Standing in the shallow hole that passed for a CP, he had calmly issued orders and served as an inspiration to all who saw him. War correspondents visiting the scene the day after the battle dubbed it "Edson's Ridge."

|