| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR Tulagi The Makin operation had not been Nimitz's first choice for an amphibious raid. In late May he had proposed an attack by the 1st Raiders against the Japanese seaplane base on Tulagi. in the lower Solomon Islands. The target was in the Southwest Pacific Area, however, and General Douglas MacArthur opposed the plan. But Tulagi remained a significant threat to the maritime lifeline to Australia. After the Midway victory opened the door for a more offensive Allied posture, the Japanese advance positions in the Solomons became a priority objective. In late June the Joint Chiefs of Staff shifted that region from MacArthur's command to Nimitz's Pacific Ocean Areas command, and ordered the seizure of Tulagi. The Americans soon discovered that the Japanese were building an airfield on nearby Guadalcanal, and that became the primary target for Operation Watchtower. The 1st Marine Division, with the 1st Raider Battalion attached, received the assignment. In answer to Edson's repeated requests, the rear echelon of his battalion (less the 81mm mortar platoon) finally joined up with him on 3 July in Samoa. The entire unit then moved on to New Caledonia. The 1st Raiders received definitive word on Watchtower on 20 July. They would seize Tulagi, with the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, in support. The 1st Parachute Battalion would take the conjoined islets of Gavutu Tanambogo. The 1st Marine Division, less one regiment in reserve, would capture the incomplete airfield on Guadalcanal.

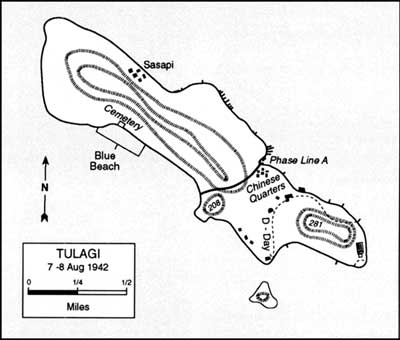

Edson offered to make amphibious reconnaissance patrols of the objectives, but the naval commander rejected that idea. Most of the information on Tulagi would come from three Australians, all former colonial officials familiar with the area. Tulagi was 4,000 yards long and no more than 1,000 yards wide, and a high ridge ran along its length, except for a low, open saddle near the southeast end. The only suitable landing beaches from a hydrographic standpoint were those on either side of this low ground, since coral formations fringed the rest of the island. Intelligence officers estimated that the island held several hundred men of the Japanese Special Naval Landing Force; these were elite troops of proven fighting ability. Aerial reconnaissance indicated they were dug in to defend the obvious landing sites. Planners thus chose to make the assault halfway up the western coast at a place designated as Beach Blue. They wisely decided to make the first American amphibious assault of the war against natural obstacles, not enemy gunfire. The raiders sailed from New Caledonia on 23 July and joined up with the main task force for rehearsals on Koro Island in the Fijis. These went poorly, since the Navy boat crews and most of the 1st Marine Division were too green. On the morning of 7 August the task force hove to and commenced unloading in what would become known as Iron-bottom Sound. Although Edson's men had trained hard on their rubber boats, they would make this landing from Higgins boats. After a preliminary bombardment by a cruiser and destroyer, the first wave, composed of Companies B and D, headed for shore. Coral forced them to debark and wade the last 100 yards, but there was no enemy opposition. Companies A and C quickly followed them. The four rifle companies spread out across the waist of the island and then advanced in line to the southeast. They met only occasional sniper fire until they reached Phase Line A at the end of the ridge, where they halted as planned while naval guns fired an additional preparation on the enemy defenses. The attack jumped off again just before noon, and promptly ran into heavy Japanese resistance. For the remainder of the day the raiders fought to gain control of the saddle from the entrenched enemy, who would not surrender under any circumstances. The Marines quickly discovered that their only recourse was to employ explosives to destroy the men occupying the caves and bunkers. As evening approached, the battalion settled into defensive lines that circled the small ridge (Hill 281) on the tip of the island. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, had already scoured the remainder of the island and now took up positions in the rear of the raiders. The Japanese launched their classic banzai counterattack at 2200 that night. The initial effort punched a small hole in the raider lines between Companies A and C. A second assault, which might have exploited this gap, instead struck full against Company As front. This time the raiders held their ground. For the remainder of the night the Japanese relied on infiltration tactics, with individuals and small groups trying to make their way into the American rear by stealth. By this means they attacked both the 2d Battalion's command post (CP) and the aid station set up near Blue Beach. They also came within 50 yards of the raider CP. Edson tried to call for reinforcements, but communications were out.

In the morning things looked much better, just as they had on Makin. At 0900 two companies of the 5th Marines passed through raider lines and swept over the southern portions of Hill 281. The remaining enemy were now isolated in a ravine in the midst of the small ridge. After a lengthy barrage by the 60mm mortars of Company E and their heavier 81mm cousins of the rifle battalion, infantrymen from both outfits moved through the final enemy pocket. Grenades and dynamite were the weapons of choice against the Japanese still holed up in their caves and dugouts. At 1500 Edson declared the island secured. That did not mean the fighting was entirely over. For the next few days Marines scoured the island by day, and fended off occasional infiltrators at night, until they had killed off the last enemy soldier. In the entire battle, the raiders suffered losses of 38 dead and 55 wounded. There were an additional 33 casualties among other Marine units on the island. All but three of the 350 Japanese defenders had died. On the night of 8 August a Japanese surface force arrived from Rabaul and surprised the Allied naval forces guarding the transports. In a brief engagement the enemy sank four cruisers and a destroyer, damaged other ships, and killed 1,200 sailors, all at minimal cost to themselves. The American naval commander had little choice the next morning but to order the early withdrawal of his force. Most of the transports would depart that afternoon with their cargo holds still half full. The raiders were in a particularly bad way. They had come ashore with little food because the plan called for their immediate withdrawal after seizing the island. Moreover, since they had not cleared the enemy from the only usable beaches until D plus 1, there had been little time to unload anything. The result would be short rations for some time to come.

The 1st Raiders performed well in their initial exposure to combat. Like their compatriots in the 2d Raiders, they were both brave and daring. Major Kenneth D. Bailey demonstrated the type of leadership that was common to both units. When an enemy machine gun held up the advance of his company on D-day, he personally circled around the bunker, crawled on top, and pushed a grenade into the firing port. In the process he received a gunshot wound in the thigh. Edson established his reputation for fearlessness by spending most of his time in the front lines, where he contemptuously stood up in the face of enemy fire. More important, he aggressively employed his force in battle, while many other senior commanders had grown timid after years of peacetime service. Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division, soon wrote Commandant Holcomb that "Edson is one of the finest troop leaders I ever saw."

|