| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

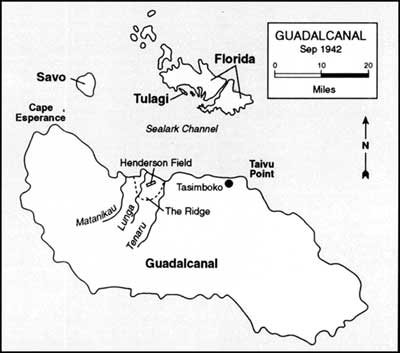

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR Tasimboko As August progressed the Japanese moved a steady stream of reinforcements to Guadalcanal in nightly runs by destroyers and barges, a process soon dubbed the "Tokyo Express." The Marines repulsed the first enemy attack at the Tenaru River on 21 August, but Vandegrift knew that he would need all the strength he could muster to defend the extended perimeter surrounding the airfield. At the end of the month he brought the raiders and parachutists across the sound and placed them in reserve near Lunga Point. The latter battalion had suffered heavily in its assault on Gavutu-Tanambogo, to include the loss of its commander, so Vandegrift attached the parachutists to Red Mike's force. Edson quickly established a rapport with Lieutenant Colonel Thomas, the division operations officer, and convinced him to use the raiders offensively. The first product of this effort was a two-company patrol on 4 September to Savo Island, where intelligence believed the enemy had an observation post. While Griffith commanded that operation, Red Mike planned a reconnaissance-in-force against Cape Esperance for the next day. When the Savo patrol returned in the late afternoon on Little (APD 4) and Gregory (APD 3), the men began debarking before they received the order to remain on board in preparation for the next mission. Once he became aware of the mix up, Edson let the offload process proceed to completion. That night Japanese destroyers of the Tokyo Express sank the two APDs. It was the second close escape for the raiders. During the shift to Guadalcanal, enemy planes had sunk the Colhoun (APD 2) just after it had unloaded a company.

Marine attention soon shifted from Cape Esperance as it became evident that the primary terminus of the Tokyo Express was the village of Tasimboko. On 6 September Edson and Thomas won permission from Vandegrift to raid the area on the eighth. After the loss of three of their APDs, shipping was at a premium, so the raiders boarded the McKean (APD 5), Manley (APD 1), and two converted tuna boats for the operation. The raider rifle companies would comprise the first echelon; the ships then would shuttle back to the Lunga for the weapons company and the parachutists. Native scouts reported there were several thousand Japanese in the area, but division planners discounted that figure. However, Edson did rely on their reports that the enemy defenses faced west toward Marine lines. He decided to land beyond the village at Taivu Point and then advance overland to take the target from the rear. When the raiders went ashore just prior to dawn on 8 September, they quickly realized the scouting reports had been accurate. As they moved along the coast toward Tasimboko, they discovered more than a thousand life preservers placed in neat rows, a large number of foxholes, and even several unattended 37mm antitank guns. In previous days Major General Kiyotaki Kawaguchi had landed an entire brigade at Tasimboko, but it was then advancing inland. Only a rearguard of about 300 men secured the village and the Japanese supply dumps located there, though this force was nearly as big as the raider first echelon. The Marines soon ran into stubborn resistance, to include 75mm artillery pieces firing pointblank down the coastal road and the orderly rows of a coconut plantation. While Edson fixed the attention of the defenders with two companies, he sent Griffith and Company A wide to the left flank. Concerned that he might be facing the enemy main force, Red Mike radioed a plea for a supplemental landing to the west of Tasimboko. The last part of the message indicated there was trouble: "If not, request instructions regarding my embarkation." Forty-five minutes later Edson again asked for fresh troops and for more air support. Division responded the same way each time — the raiders were to break off the action and withdraw. Red Mike ignored that order and continued the attack. Not long afterwards, enemy resistance melted away, and both wings of the raider force entered the village around noon. The area was stockpiled with large quantities of food, ammunition, and weapons ranging up to 75mm artillery pieces. Vandegrift radioed a "well done" and repeated his order to withdraw yet again.

The raider commander chose to stay put for the time being, and his men set about destroying as much of the cache as they could. Troops wrecked a powerful radio station, bayoneted cans of food, tore open bags of rice and urinated on the contents or spilled them on the ground, tied guns to landing boats and towed them into deep water, and then finally put the torch to everything that was left. They also gathered all available documents. As the sun went down, the men reembarked and headed for the perimeter, many of them a little bit heavier with liberated chow, cigarettes, and alcohol. The raid was a minor tactical victory in terms of actual fighting. The Marines counted 27 enemy bodies and estimated they had killed 50. Their own losses were two dead and six wounded. But the battle had important repercussions. The raiders had put a serious dent in Japanese logistics, fire support, and communications. The intelligence gathered had more far-reaching consequences, since it revealed many of the details of the coming Japanese offensive. Finally, the setback hurt the enemy's morale and further boosted that of the raiders. They had defeated the Japanese yet again, and were literally feasting on the fruits of the victory.

|