| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

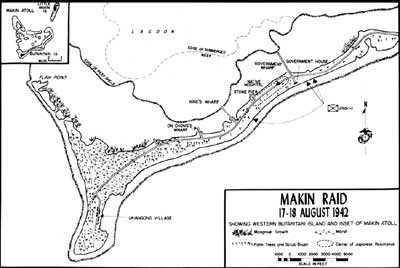

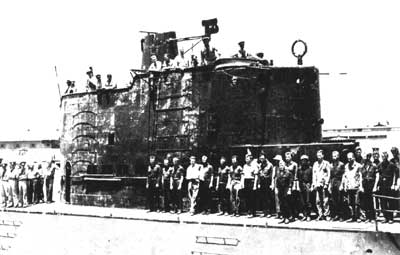

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR Makin During the summer of 1942 Admiral Nimitz decided to employ Carlson's battalion for its designated purpose. Planners selected Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands as the target. They made available two large mine-laying submarines, the Nautilus and the Argonaut. Each one could carry a company of raiders. The force would make a predawn landing on Butaritari Island, destroy the garrison (estimated at 45 men), withdraw that evening, and land the next day on Little Makin Island. The scheduled D-day was 17 August, 10 days after the 1st Marine Division and the 1st Raiders assaulted the lower Solomons. The objectives of the operation were diverse: to destroy installations, take prisoners, gain intelligence on the area, and divert Japanese attention and reinforcements from Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Companies A and B drew the mission and boarded the submarines on 8 August. Once in the objective area, things began to go badly. The subs surfaced in heavy rain and high seas. Due to the poor conditions, Carlson altered his plan at the last minute. Instead of each company landing on widely separated beaches, they would go ashore together. Lieutenant Oscar F. Peatross, a platoon commander, did not get the word; he and the squad in his boat ended up landing alone in what became the enemy rear. The main body reached shore in some confusion due to engine malfunctions and weather, then the accidental discharge of a weapon ruined any hope of surprise.

First Lieutenant Merwyn C. Plumley's Company A quickly crossed the narrow island and turned southwest toward the known enemy positions. Company B, commanded by Captain Ralph H. Coyt, followed in trace as the reserve. Soon thereafter the raiders were engaged in a firefight with the Japanese. Sergeant Clyde Thomason died in this initial action while courageously exposing himself in order to direct the fire of his platoon. He later was awarded the Medal of Honor, the first enlisted Marine so decorated in World War II. The raiders made little headway against Japanese machine guns and snipers. Then the enemy launched two banzai attacks, each announced with a bugle call. Marine fire easily dispatched both groups of charging enemy soldiers. Unbeknownst to the Americans, they had nearly wiped out the Japanese garrison at that point in the battle.

At 1130 two enemy aircraft appeared over the island and scouted the scene of action. Carlson had trained his men to remain motionless and not fire at planes. With no troops in sight and no contact from their own ground force, the planes finally dropped their bombs, though none landed within Marine lines. Two hours later 12 planes arrived on the scene, several of them seaplanes. Two of the larger flying boats landed in the lagoon. Raider machine guns and Boys antitank rifles fired at them. One burst into flame and the other crashed on takeoff after receiving numerous hits. The remaining aircraft bombed and strafed the island for an hour, again with most of the ordnance hitting enemy-occupied territory. Another air attack came late in the afternoon. The natives on the island willingly assisted the Americans throughout the day. They carried ammunition and provided intelligence. The latter reports suggested that enemy reinforcements had come ashore from the seaplanes and from two small ships in the lagoon. (The submarines later took the boats under indirect fire with their deck guns and miraculously sunk both.) Based on this information, Carlson was certain there was still a sizable Japanese force on the island. At 1700 he called several individuals together and contemplated his options. Roosevelt and the battalion operations officer argued for a withdrawal as planned in preparation for the next day's landing on Little Makin. Concerned that he might become too heavily engaged if he tried to advance, Carlson decided to follow their recommendation. This part of the operation went smoothly for a time. The force broke contact in good order and a group of 20 men covered the rest of the raiders as they readied their rubber boats and shoved off. Carlson, however, forgot about the covering force and thought his craft contained the last men on the island when it entered the water at 1930. Disaster then struck in the form of heavy surf. The outboard engines did not work and the men soon grew exhausted trying to paddle against the breakers. Boats capsized and equipment disappeared. After repeated attempts several boat loads made it to the rendezvous with the submarines, but Carlson and 120 men ended up stranded on the shore. Only the covering force and a handful of others had weapons. In the middle of the night a small Japanese patrol approached the perimeter. They wounded a sentry, but not before he killed three of them. With the enemy apparently still full of fight and his raiders disorganized and weakened, Carlson called another council of war. Without much input from the others, he decided to surrender. His stated reasons were concern for the wounded, and for the possible fate of the president's son (who was not present at the meeting). At 0330 Carlson sent his operations officer and another Marine out to contact the enemy. They found one Japanese soldier and eventually succeeded in giving him a note offering surrender. Carlson also authorized every man to fend for himself — those who wished could make another attempt to reach the submarines. By the next morning several more boatloads made it through the surf, including one with Major Roosevelt. In the meantime, a few exploring raiders killed several Japanese, one of them probably the man with the surrender note. With dawn the situation appeared dramatically better. The two-man surrender party reported that there appeared to be no organized enemy force left on the island. There were about 70 raiders still ashore, and the able-bodied armed themselves with weapons lying about the battlefield. Carlson organized patrols to search for food and the enemy. They killed two more Japanese soldiers and confirmed the lack of opposition. The raider commander himself led a patrol to survey the scene and carry out the demolition of military stores and installations. He counted 83 dead Japanese and 14 of his own killed in action. Based on native reports, Carlson thought his force had accounted for more than 160 Japanese. Enemy aircraft made four separate attacks during the day, but they inflicted no losses on the raider force ashore. The Marines contacted the submarines during the day and arranged an evening rendezvous off the entrance to the lagoon, where there was no surf to hinder an evacuation. The men hauled four rubber boats across the island and arranged for the use of a native outrigger. By 2300 the remainder of the landing force was back on board the Nautilus and Argonaut. Since the entire withdrawal had been so disorganized, the two companies were intermingled on the submarines and it was not until they returned to Pearl Harbor that they could make an accurate accounting of their losses. The official tally was 18 dead and 12 missing.

Only after the war would the Marine Corps discover that nine of the missing raiders had been left alive on the island. These men had become separated from the main body at one point or another during the operation. With the assistance of the natives the group evaded capture for a time, but finally surrendered on 30 August. A few weeks later the Japanese beheaded them on the island of Kwajalein. The raid itself had mixed results. Reports painted it as a great victory and it boosted morale on the home front. Many believed it achieved its original goal of diverting forces from Guadalcanal, but the Japanese had immediately guessed the size and purpose of the operation and had not let it alter their plans for the Solomons. However, it did cause the enemy to worry about the potential for other such raids on rear area installations. On the negative side, that threat may have played a part in the subsequent Japanese decision to fortify heavily places like Tarawa Atoll, the scene of a costly amphibious assault later in the war. At the tactical level, the 2d Raiders had proven themselves in direct combat with the enemy. Their greatest difficulties had involved rough seas and poor equipment; bravery could not fix those limitations. Despite the trumpeted success of the operation, the Navy never again attempted to use submarines to conduct raids behind enemy lines. Carlson received the Navy Cross for his efforts on Makin, and the public accorded him hero status. A new of those who served with him were not equally pleased with his performance. No one questioned his demonstrated bravery under fire, but some junior officers were critical of his leadership, especially the attempt to surrender to a non-existent enemy. Carlson himself later noted that he had reached "a spiritual low" on the night of the 17th. And again on the evening of the 18th, the battalion commander contemplated remaining on the island to organize the natives for resistance, while others supervised the withdrawal of his unit. Those who criticized him thought he had lost his aggressiveness and ability to think clearly when the chips were down. But he and his raiders would have another crack at the enemy in the not too distant future.

|