| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR

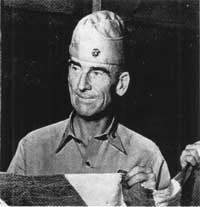

Creating the Raiders Two completely independent forces were responsible for the appearance of the raiders in early 1942. Several historians have fully traced one of these sets of circumstances, which began with the friendship developed between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Evans F. Carlson. As a result of his experiences in China, Carlson was convinced that guerrilla warfare was the wave of the future. One of his adherents in 1941 was Captain James Roosevelt, the president's son. At the same time, another presidential confidant, William J. Donovan, was pushing a similar theme. Donovan had been an Army hero in World War I and was now a senior advisor on intelligence matters. He wanted to create a guerrilla force that would infiltrate occupied territory and assist resistance groups. He made a formal proposal along these lines to President Roosevelt in December 1941. In January, the younger Roosevelt wrote to the Major General Commandant of the Marine Corps and recommended creation of "a unit for purposes similar to the British Commandos and the Chinese Guerrillas." These ideas were appealing at the time because the war was going badly for the Allies. The Germans had forced the British off the continent of Europe, and the Japanese were sweeping the United States and Britain from much of the Pacific. The military forces of the Allies were too weak to slug it out in conventional battles with the Axis powers, so guerrilla warfare and quick raids appeared to be viable alternatives. The British commandos had already conducted numerous forays against the European coastline, and Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill enthusiastically endorsed the concept to President Roosevelt. The Marine Commandant, Major General Thomas Holcomb, allegedly succumbed to this high-level pressure and organized the raider battalions, though he himself thought that any properly trained Marine unit could perform amphibious raids. That scenario is mostly accurate, but it tells only half of the story. Two other men also were responsible for the genesis of the raiders. One was General Holland M. Smith. Although the Marine Corps Schools had created the first manual on amphibious operations in 1935, during the early days of World War II Smith faced the unenviable task of trying to convert that paper doctrine into reality. As a brigadier general he commanded the 1st Marine Brigade in Fleet Landing Exercise 6, which took place in the Caribbean in early 1940. There he discovered that several factors, to include the lack of adequate landing craft, made it impossible to rapidly build up combat power on a hostile shore. The initial assault elements would thus be vulnerable to counterattack and defeat while most of the amphibious force remained on board its transports. As a partial response to this problem, Smith seized upon the newly developed destroyer transport. During FLEX 6, his plan called for the Manley (APD 1) to land a company of the 5th Marines via rubber boats at H-minus three hours (prior to dawn) at a point away from the primary assault beach. This force would advance inland, seize key terrain dominating the proposed beachhead, and thus protect the main landing from counterattack. A year later, during FLEX 7, Smith had three destroyer transports. He designated the three companies of the 7th Marines embarked on these ships as the Mobile Landing Group. During the exercise these units again made night landings to protect the main assault, or conducted diversionary attacks. Major General Merritt A. Edson, USMC

Merritt A. Edson's military career began in the fall of 1915 when he enlisted in the 1st Vermont Infantry (a National Guard outfit). In the summer of 1916 he served in the Mexican border campaign. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, he earned a commission as a Marine officer, but he did not arrive in France until just before the Armistice. He ultimately more than made up for missing out on "the war to end all wars." In 1921 he began his long career in competitive shooting as part of the 10-man team that won the National Rifle Team Trophy for the Marine Corps. He earned his pilot's wings in 1922 and flew for five years before poor depth perception forced him back into the infantry. In 1927, he received command of the Marine detachment on board the Denver (CL 16). He and his men soon became involved in the effort to rid Nicaragua of Augusto Sandino. Edson spent 14 months ashore, most of it deep in the interior of the country. In the process, he won a reputation as an aggressive, savvy small-unit leader. He bested Sandino's forces in more than a dozen skirmishes, earned his first Navy Cross for valor, and came away with the nickname "Red Mike" (in honor of the colorful beard he sported in the field). Edson spent the first half of the 1930s as a tactics instructor at the Basic School for new lieutenants, and then as ordnance officer at the Philadelphia Depot of Supplies. During the summers he continued to shoot; ultimately he captained the rifle team to consecutive national championships in 1935 and 1936. In the summer of 1937 he transferred to Shanghai to become the operations officer for the 4th Marines. He arrived just in time for a ringside seat when the Sino-Japanese War engulfed that city. That gave him ample opportunity to observe Japanese combat techniques at close range. In June 1941, Red Mike assumed command of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines at Quantico. After his stint with the 1st Raiders and the 5th Marines on Guadalcanal, Edson remained in the Pacific. He served as chief of staff of the 2d Marine Division at Tarawa, and as assistant division commander on Saipan and Tinian. During each of these campaigns he again distinguished himself under fire. Ultimately, the Marine Corps discovered that Edson's courage was matched by his skill as a staff officer. He spent nine months as chief of staff for the Fleet Marine Force Pacific and closed out the war in charge of the Service Command. Following the war Edson headed the effort to preserve the Marine Corps in the face of President Truman's drive to "unify" the services. He waged a fierce campaign in the halls of Congress, in the media, and in public appearances across the nation. Finally, he resigned his commission in order to testify publicly before committees of both houses of Congress. His efforts played a key role in preserving the Marine Corps. After stints as the Commissioner of Public Safety in Vermont, and as Executive Director of the National Rifle Association, Edson died in August 1955. Smith eventually crystallized his new ideas about amphibious operations. He envisioned making future assaults with three distinct echelons. The first wave would be composed of fast-moving forces that could seize key terrain prior to the main assault. This first element would consist of a parachute regiment, an air infantry regiment (gliderborne troops), a light tank battalion, and "at least one APD [highspeed destroyer transport] battalion." With a relatively secure beachhead, the more ponderous combat units of the assault force would come ashore. The third echelon would consist of the reserve force and service units. In the summer of 1941 Smith was nearly in a position to put these ideas into effect. He now commanded the Amphibious Force Atlantic Fleet (AFAF), which consisted of the 1st Marine Division and the Army's 1st Infantry Division. During maneuvers at the recently acquired Marine base at New River, North Carolina, Smith embarked the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, in six APDs and made it an independent command reporting directly to his headquarters. The operations plan further attached the Marine division's sole company of tanks and its single company of parachutists to the APD battalion. The general did not use this task force to lead the assault, but instead landed it on D plus 2 of the exercise, on a beach well in the rear of the enemy's lines. With all aviation assets working in direct support, the mobile force quickly moved inland, surprised and destroyed the enemy reserves, and took control of key lines of communication. Smith called it a "spearhead thrust around the hostile flank." The AFAF commander had not randomly selected the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, for this role. In June 1941 he personally had picked Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. "Red Mike" Edson to command that battalion and had designated it to serve permanently with the Navy's APD squadron. Smith began to refer to Edson's outfit as the "light battalion" or the "APD battalion." When the 5th Marines and the other elements of the 1st Marine Division moved down to New River that fall, the 1st Battalion remained behind in Quantico with Force headquarters. Reports going to and from AFAF placed the battalion in a category separate from the rest of the division of which it was still technically a part. Lieutenant Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, the division operations officer, ruefully referred to the battalion as "the plaything of headquarters." Edson's unit was unique in other ways. In a lengthy August 1941 report, the lieutenant colonel evaluated the organization and missions of his unit. He believed that the APD battalion would focus primarily on reconnaissance, raids, and other special operations — in his mind it was a waterborne version of the parachutists. In a similar fashion, the battalion would rely on speed and mobility, not firepower, as its tactical mainstay. Since the APDs could neither embark nor offload vehicles, that meant the battalion had to be entirely foot mobile once ashore, again like the parachutists. To achieve rapid movement, Edson recommended a new table of organization that made his force much lighter than other infantry battalions. He wanted to trade in his 81mm mortars and heavy machine guns for lighter models. There also would be fewer of these weapons, but they would have larger crews to carry the ammunition. Given the limitations of the APDs, each company would be smaller than its standard counterpart. There would be four rifle companies, a weapons company, and a headquarters company with a large demolitions platoon. The main assault craft would be 10-man rubber boats. The only thing that kept Smith from formally removing the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, from the 1st Marine Division was the lack of troops to make the regiment whole again. As it was, many units of the division still existed only on paper in the fall of 1941. At the very beginning of 1942, with the United States now at war and recruits pouring into the Corps, Smith wrote the Major General Commandant and asked him to redesignate the battalion. On 7 January Edson received word that he now headed the 1st Separate Battalion. Brigadier General Evans F. Carlson, USMC

Evans F. Carlson got an early start in his career as a maverick. He ran away from his home in Vermont at the age of 14 and two years later bluffed his way past the recruiters to enlist in the Army. When war broke out in 1917, he already had five years of service under his belt. Like Merritt A. Edson, he soon won a commission, but arrived at the front too late to see combat. After the war he tried to make it as a salesman, but gave that up in 1922 and enlisted in the Marine Corps. In a few months he earned a commission again. Other than a failed attempt at flight school, his first several years as a Marine lieutenant were unremarkable. In 1927 Carlson deployed to Shanghai with the 4th Marines. There he became regimental intelligence officer and developed a deep interest in China that would shape the remainder of his days. Three years later, commanding an out post of the Guardia Nacional in Nicaragua, he had his first brush with guerrilla warfare. That became the second guiding star of his career. In his only battle, he successfully engaged and dispersed an enemy unit in a daring night attack. There followed a tour with the Legation Guard in Peking, and a stint as executive officer of the presidential guard detachment at Warm Springs, Georgia. In the latter job Carlson came to know Franklin D. Roosevelt. Captain Carlson arrived in Shanghai for his third China tour in July 1937. Again like Edson, he watched the Japanese seize control of the city. Detailed to duty as an observer, Carlson sought and received permission to accompany the Chinese Communist Party's 8th Route Army, which was fighting against the Japanese. For the next year he divided his time between the front lines and the temporary Chinese capital of Hangkow. During that time he developed his ideas on guerrilla warfare and ethical indoctrination. When a senior naval officer censured him for granting newspaper interviews, Carlson returned to the States and resigned so that he could speak out about the situation in China. He believed passionately that the United States should do more to help the Chinese in their war with Japan. During the next two years Carlson spoke and wrote on the subject, to include two books (The Chinese Army and Twin Stars of China), and made another trip to China. With war looming for the United States, he sought to rejoin the Corps in April 1941. The Commandant granted his request, made him a major in the reserves, and promptly brought him onto active duty. Ten months later he created the 2d Raider Battalion. After his departure from the raiders in 1943, Carlson served as operations officer of the 4th Marine Division. He made the Tarawa landing as an observer and participated with his division in the assaults on Kwajalein and Saipan. In the latter battle he received severe wounds in the arm and leg while trying to pull his wounded radio operator out of the line of fire of an enemy machine gun. After the war Carlson retired from the Marine Corps and made a brief run in the 1946 California Senate race before a heart attack forced him out of the campaign. He died in May 1947. A week later James Roosevelt wrote his letter to the Commandant about raid forces. On 14 January General Holcomb sought the reaction of his senior generals to the President's plan to place Donovan in charge of a Marine Corps version of the commandos. In his 20 January reply to the younger Roosevelt, the Major General Commandant pointed out that "the APD Battalion. . . is organized, equipped, and trained for this duty, including in particular the use of rubber boats in night landings." He expressed the hope that the Navy would make destroyer transports available on the West Coast in the near future to support organization of a second APD battalion there. Holcomb obviously intended to use Smith's new force as a convenient means to channel outside interference toward a useful end. His plan did not entirely work. On 23 January the Navy leadership, undoubtedly in response to political pressure, directed the Pacific Fleet to put together a commando-type unit. The 2d Separate Battalion officially came to life on 4 February. To ensure that this new organization developed along proper lines, the Commandant ordered Edson to transfer a one-third slice of his unit to California as a cadre for the 2d Battalion, which initially only on paper. Headquarters also adopted Red Mike's recommended tables of organization and promulgated them to both battalions. The only change was the addition of an 81mm mortar platoon (though there was no room on the ships of the APD squadron to accommodate the increase). Holcomb even offered to transfer Edson to the 2d Separate, but in the end the Commandant allowed the commanding general of the 2d Marine Division, Major General Charles F. B. Price, to place Major Carlson in charge. James Roosevelt became the executive officer of the unit. In mid-February, at Price's suggestion, the Major General Commandant redesignated his new organizations as Marine Raider Battalions. Edson's group became the 1st Raiders on 16 February; Carlson's outfit was redesignated to the 2d Raiders three days later.

|