| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

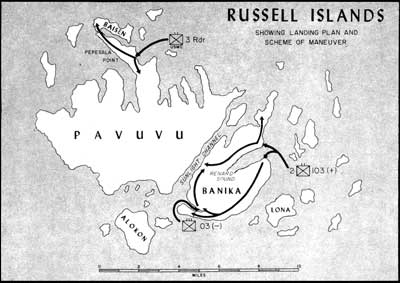

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR New Georgia As the fighting on Guadalcanal drew to a close in early 1943, American commanders intensified their planning for the eventual seizure of Rabaul, the primary Japanese stronghold in the Southwest Pacific. This major air and naval base on the eastern end of New Britain was centrally located between New Guinea and the northwestern terminus of the Solomons. That allowed the Japanese to shift their air and naval support from one front to the other on short notice. Conversely, simultaneous American advances through New Guinea and the Solomons would threaten Rabaul from two directions. With that in mind, Admiral William F. Halsey's South Pacific command prepared to drive farther up the Solomons chain, while MacArthur continued his operations along the New Guinea coast. Halsey's planners initially focused on New Georgia, a large island located on the southern flank of the Slot about halfway up the Solomons chain. By December 1942, the Japanese had managed to complete an airstrip on New Georgia's Munda Point. Seizure of the island would thus remove that enemy threat and advance Allied aircraft one-third of the way to Rabaul. However, the South Pacific command also was worried about enemy activity in the Russell Islands, located 30 miles northwest of Guadalcanal's Cape Esperance. The Russells had been a staging point for the enemy's reinforcement and subsequent evacuation of Guadalcanal. Strong Japanese forces there would be a thorn in the side of an operation against New Georgia and possibly a threat to Guadalcanal itself. Halsey thus decided to seize the Russells prior to action elsewhere in the Solomons. As an additional benefit, American fighter planes stationed in the Russells would be able to provide more effective support to the eventual assault on New Georgia. The landing force for Operation Cleanslate (the codename for the Russells assault) consisted of the 43d Infantry Division and the 3d Raider Battalion. The Army division would seize Banika Island while the Marines took nearby Pavuvu. The APDs of Transdiv 12 carried the raiders from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal in mid-February. Four days prior to the 21 February D-day, a lieutenant and a sergeant from the raiders scouted both objectives — they found them empty of the enemy. The 3d Raiders thus made an unopposed landing in their first offensive action. The 159th Infantry followed them ashore and assisted in the occupation of the island. The greatest challenges the Marines faced on Pavuvu were logistical and medical. Due to the Navy's legitimate concern about an enemy air and naval response, the landing plan relied on a rapid offload and quick withdrawal of the transports. The Higgins boats of the APDs were preloaded with raider supplies, while the men went ashore in their rubber boats. A rash of outboard motor failures played havoc with the landing formations, and Liversedge's after action report noted that this could have resulted in "serious consequences." Once ashore, the light raiders suffered from their lack of organic transport as they struggled to man handle supplies from the beach to inland dumps. During the battalion's subsequent four-week stay on Pavuvu, the diet of field chow and the tough tropic conditions combined to debilitate the troops. Fully one-third developed skin problems, all men lost weight, and several dozen eventually fell ill with malaria and other diseases. Although it was not entirely the fault of planners, the hard-hitting capabilities of the Marine battalion were wasted on Cleanslate. Only the two-man scouting team had performed a mission in accordance with the original purpose of the raiders.

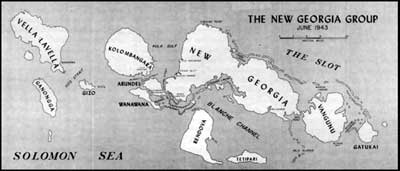

In the midst of the execution of Cleanslate Halsey continued preparations for subsequent operations in the Central Solomons. This included repeated use of the scouting capability demonstrated in the Russells. At the end of February a Navy lieutenant and six raiders landed at New Georgia's Roviana Lagoon. With the aid of coastwatchers and natives, they spent the next three weeks collecting information on the terrain, hydrographic conditions, and Japanese defenses. On 21 March Consolidated Catalina PBYs landed four raider patrols at New Georgia's Segi Point. From there they fanned out with native guides and canoes to scout Kolombangara, Vangunu, and New Georgia. Other groups visited these areas and Rendova over the course of the next three months. The patrols provided valuable information that helped shape landing plans, and the final groups emplaced small detachments near designated beaches to act as guides for the assault forces. During May and June the Japanese reinforced their garrisons in the central Solomons to 11,000 men, but this number was grossly insufficient to cover all potential landing sites on the numerous large islands in the region. That gave Halsey's force great flexibility. The final plan called for several assaults, all against lightly defended or undefended targets. On D-day the Eastern Landing Force, consisting of the 103d Infantry, an Army regiment, and the 4th Raider Battalion, would occupy Wickham Anchorage, Segi Point, and Viru Harbor. Naval construction units would immediately build a fighter strip at Segi and a base for torpedo boats at Viru. The Northern Landing Group (the 1st Raider Regiment headquarters, the 1st Raider Battalion, and two army battalions) would simultaneously go ashore at Rice Anchorage, then attack overland to take Enogai Inlet and Bairoko Harbor. This would cut off the Japanese barge traffic that supplied reinforcements and logistics. The last D-day operation would be the Southern Landing Group's seizure of the northern end of Rendova and its outlying islands. On D plus 4 many of these same units from the 43d Infantry Division would conduct a shore-to-shore assault against the undefended beaches at Zanana and Piraka on New Georgia. Planes from Segi Point and artillery from the Rendova beachhead would render support as the Army regiments advanced overland to capture Munda airfield. D-day was 30 June.

Things did not go entirely according to plan. During June the Japanese used some of their reinforcements to extend their coverage of New Georgia. They ordered a battalion to Viru with instructions to clean out native forces operating in the vicinity of Segi. The Solomon Islanders, under command of Coastwatcher Donald G. Kennedy, had repeatedly attacked enemy outposts and patrols in the area. As the Japanese battalion advanced units closer to Segi Point, Kennedy requested support. On 20 June Admiral Turner ordered Lieutenant Colonel Currin and half of his 4th Raiders to move immediately from Guadalcanal to Segi. Companies O and P loaded on board APDs that day and made an unopposed landing the next morning. On 22 June two Army infantry companies and the advance party of the airfield construction unit arrived to strengthen the position. Vim presented a tougher problem. The narrow entrance to the harbor was flanked by high cliffs and covered by a 3-inch coast defense gun. Numerous enemy machine guns, including .50-caliber models, occupied supporting positions. Most of the defenses were oriented toward an attack from the sea, so American leaders quickly decided to conduct an overland approach. But that was not easy either,given the difficulty of the trails. After reconnaisance and consultation with higher headquarters, Currin decided to take his raiders by rubber boat to Regi, where they would begin their trek. The assault on Viru would be a double envelopment. Lieutenant Devillo W. Brown's 3d Platoon, designated Task Force B, would take the lightly defended village of Tombe on the eastern side of the harbor. The remainder of the force would attack the main enemy defenses at Tetemara on the opposite shore. The simultaneous assaults were to take place on the originally scheduled D-day. Once the approaches were secured, APDs would land two Army infantry companies.

The Marines departed Segi the evening of 27 June and landed at Regi just after midnight. They rested a few hours and then moved out single file on the narrow trail. Company O took the lead with Company P bringing up the rear. Native scouts served as guides and the point. The small force had not gone very far when the path disappeared into a swamp. After three hours of tough movement, firing erupted at the end of the column. One of the Japanese patrols known to be in the area had stumbled upon the rear guard. The raiders killed four of the enemy and suffered no casualties. About an hour later a Japanese force of about 20 men, possibly the same force, came up from a side trail and hit the rear guard in the flank. After an hour of firing the enemy broke off the action. There were no known casualties on either side, but the five-man rear point failed to rejoin the Marine column. (They later turned up back at Segi.) The raiders crossed the Mohi River late in the afternoon and set up a perimeter defense for the night. The wicked terrain and the two forced halts convinced Currin that he would not make it to Viru in time for D-day. Since he no longer had any working radios, he sent two native runners to Kennedy asking him to relay a message to higher command that the 4th Raiders would be a day late in making its attack. After a miserable rainy night, the Marines moved out. They reached the Choi River late in the morning. As the rear elements crossed, an enemy force on a hill 300 yards to the battalion's flank opened up with heavy fire from machine guns and rifles. The battalion halted again as Currin tried to determine what was transpiring. After about three hours he knew that his rear had successfully engaged a small unit, probably another enemy patrol, so the remainder of the force proceeded on its way. The raiders crossed the snake-like Choi River twice more before halting for the night at 1800. The 3d Platoon reached the perimeter at 2100. They had lost five killed and another man was wounded, but they had counted 18 enemy dead. It seemed likely that the enemy at Viru was now aware of the Marine presence. Since the native scouts indicated that the area north of the harbor was considered impassable, Currin suspected that the Japanese would reinforce Tombe against an attack from the east. In view of that and the losses to Brown's unit, the colonel decided to strengthen that wing of his assault. Captain Anthony "Cold Steel" Walker would now lead two platoons of his Company P against Tombe. Given the difficulties with the terrain and communications, there would be no attempt to coordinate the two arms of the envelopment; Walker was free to attack whenever he chose after dawn on 1 July. With the plans finalized, the raiders settled in for another night of rain. The battalion resumed the march early the next morning, but Walker's unit soon branched off on the shorter route to Tombe. During the course of the day the main force crossed several ridges and the Viru and Tita rivers. Everyone, to include the native bearers carrying the heavy weapons ammunition, felt exhausted. But the worst was yet to come. In twilight the Marines had to ford the Mango, a wide, swift river that was at least six feet deep. They formed a human chain and somehow managed to get everyone across without incident. The tough hills now disappeared, but in their place was a mangrove swamp waist deep. In the pitch darkness the men stumbled forward through the mess of water, roots, and mud. Finally the natives brought forward bits of rotting jungle vegetation from the banks of the Mango. With this luminescent material on their backs, each raider could at least follow the man in front. At the end of the swamp was a half mile climb to the top of a ridge where the unit could rest and prepare for the attack. The nightly rain and the struggles of hundreds of men soon made the steep slope nearly impassable. Several hours after nightfall the battalion finally reached level ground and the Marines huddled on the sides of the trail until dawn. Unbeknownst to the raiders, the amphibious portion of the assault against Viru had taken place as previously scheduled. Although the Navy commander in charge was aware of Currin's message altering the date of the land attack, he chose to order his APDs to approach the harbor on 30 June. The Japanese 3-inch gun quickly drove them off. Unable to contact Currin, higher headquarters then decided to land the Army force embarked in the APDs near the same spot where the raiders had begun their trek. The new mission was to move overland and support the Marines, who were apparently experiencing difficulties. The Japanese commander at Viru reported that he had repulsed an American landing.

Both wings of the raider assault force moved out early on the morning of 1 July. By 0845 Walker's detachment reached the outskirts of Tombe without being discovered. The men deployed, opened fire on the tiny village, and then rushed forward. Most of the defenders apparently died in the initial burst of fire. The two Marine platoons secured the village without a single casualty and counted 13 enemy bodies. Just as that engagement came to a close, six American aircraft appeared over the harbor. These were not part of the original plan, but headquarters had sent them to soften up the objective when it realized that the raider attack would be delayed. Although this uncoordinated air support could have resulted in disaster, it worked out well in practice. The planes ignored Tombe and concentrated their efforts on Tetemara. The Japanese abandoned some of their fixed defenses and moved inland, directly into the path of the oncoming raiders. Currin's point made contact with the enemy shortly after the bombing ceased. Company O, leading the battalion column, quickly deployed two platoons on line astride the trail. The raiders continued forward and destroyed Japanese outposts, but then ran into the enemy main body, which was bolstered by several machine guns. Progress then was painfully slow as intermittent heavy rains swept the battlefield. Company O's reserve platoon went into line to the left as noise indicated that the enemy might be gathering there for a counterattack. As the day wore on the raiders pushed the Japanese back, until the Marine right flank rested on high ground overlooking the harbor. Currin fed some of Company P's machine guns into the line, then put his remaining platoon (also from Company P) on his right flank. Demolitions men moved forward to deal with the enemy machine guns. In mid-afternoon a handful of Japanese launched a brief banzai attack against the Marine left. Not long after this effort dissolved, Currin launched Lieutenant Malcolm N. McCarthy's Company P platoon against the enemy's left flank, while Company O provided a base of fire. McCarthy's men quickly overran the 3-inch gun and soon rolled up the enemy line, as the remainder of the Japanese defenders withdrew toward the northwest. The raiders had suffered 8 dead and 15 wounded, while killing 48 of the enemy and capturing 16 machine guns and a handful of heavier weapons. The 4th Raiders consolidated its hold on Viru and conducted numerous patrols over the next several days. The two Army companies landed near Regi finally reached Tombe on 4 July. The Navy brought in more Army units on 9 July and the Marines boarded the LCIs for Guadalcanal. The other half of the 4th Raider Battalion (Companies N and Q) received its baptism of fire during this same period. This unit was under command of the battalion executive officer, Major James R. Clark. It was assigned to assist the Army's 2d Battalion, 103d Infantry (Lieutenant Colonel Lester E. Brown) in seizing Vangunu and the approaches to Wickham Anchorage on 30 June. Intelligence from the coastwatchers indicated that there were about 100 Japanese occupying the island. The plan called for the raiders to make a predawn landing at undefended Oloana Bay. The Army would follow them ashore after daylight, establish a beachhead, and then deal with the enemy, thought to be located in a village along the coast several miles to the east. The night landing under conditions of low visibility and heavy seas turned into a fiasco. The APDs began debarkation in the wrong spot, their Higgins boats lost formation when they attempted to pass through the LCIs loaded with soldiers, and the two raider companies ended up being scattered along seven miles of coastline. When the Army units began to land after daylight, they found just 75 Marines holding the designated beachhead. A two-man patrol (one lieutenant each from the raiders and the Army battalion) had been ashore since mid-June to reconnoiter with the aid of native scouts. They provided the exact location of the Japanese garrison, and the joint force soon headed to the northeast toward its objective. Native scouts and the handful of Marines led the way, with two Army companies (F and G) in trace. The remaining raiders were to join up with their unit as soon as they could. All but one platoon did catch up by the time the Americans reached their line of departure a few hundred yards north of the village.

The plan of attack was simple. The Army units passed through the raiders on the east-west trail to assume the eastern-most position. The entire column of files then merely faced to the right, which placed the composite battalion on line and pointing toward the enemy to the south. Company Q held the right flank on the bank of the Kaeruka River. Company N in the center and Company F on the left flank would guide on the movements of Q. Company G held back and acted as the reserve. Within minutes of beginning the advance, the attack ran into resistance. Japanese fire from the west bank of the river was particularly heavy and Company Q crossed over to deal with this threat. At the same time Company F moved to its left to skirt around strong defenses. Company G soon moved in to fill the gap. By late afternoon the Americans were able to clear the east bank of the river. Lieutenant Colonel Brown ordered Company Q to disengage from the west bank and join in the battalion's perimeter defense at the mouth of the river. The Marines had lost 10 dead and 21 wounded, while the Army had suffered similarly. The enemy made no ground attack that night, but periodically fired mortars and machine guns at American lines. During a lull at 0200 three Japanese barges approached the beach, apparently unaware that ownership of the real estate was under dispute. As they neared shore, the Marines guarding the seaward portion of the perimeter opened up. One craft sank and the other two broached in the surf. Two Marines and one soldier died in the firefight, but the entire enemy force, estimated at 120 men, was destroyed in the water or on the beach. The next morning Brown decided to disengage and move to Vura Village, where he could reorganize and direct fire support on the remaining enemy at Kaeruka prior to launching another attack. The Americans received only harassing fire as they withdrew. After a day of preparatory fire by air, artillery, and naval guns, the composite battalion returned to Kaeruka on 3 July. They seized the village against minimal resistance, killed seven more Japanese, and captured one. The raiders returned to Oloana Bay by LCI later the next day. On 9 July they made a predawn landing from an LCT on Gatukai Is land to investigate reports of a 50-man Japanese unit. The Marines found evidence of the enemy but made no contact. They returned to Oloana Bay on 10 July and departed for Guadalcanal the day after. There they joined up with Lieutenant Colonel Currin and the rest of the 4th Raider Battalion.

|