| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

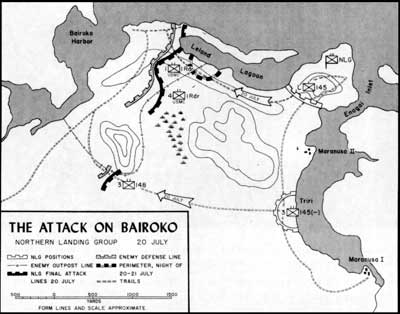

FROM MAKIN TO BOUGAINVILLE: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War by Major Jon T Hoffman, USMCR Bairoko Things were worse for the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry. After breaking off from the line of march of the 1st Raiders on 6 July, the soldiers had moved over equally difficult terrain to assume their blocking position on the Munda-Bairoko Trail on 8 July. After initial success against surprised Japanese patrols, the Army battalion fought a bloody action against an enemy force of similar strength that pushed the American soldiers off high ground and away from the important trail. Heavy jungle and poor maps prevented aerial resupply of their position, while illness and casualties sapped manpower. Liversedge led a reinforcing company from the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry, to the scene on 13 July. Disappointed at the results of this portion of the operation, and unable to reinforce or resupply this outpost adequately, the raider colonel decided to withdraw the force to Triri. There the soldiers would recuperate for the upcoming move on Bairoko and disrupt enemy movement on the Munda-Bairoko Trail with occasional patrols. Prior to dawn on 18 July four APDs brought the 4th Raider Battalion and fresh supplies to Enogai. Most of the Rice Anchorage garrison had also moved up to join the main force. This gave Liversedge four battalions, but all of them were significantly understrength due to losses already suffered in the New Georgia campaign. The 4th Raider Battalion was short more than 200 men. The 1st Raiders reorganized into two full companies (B and D), with A and C becoming skeleton units. A detachment of the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry, remained at Rice Anchorage. More important, the enemy at Bairoko was now aware of the threat to its position. Marine patrols in mid-July noted that the Japanese were busily fortifying the landward approaches to their last harbor on the north coast of the island.

Liversedge issued his order for the attack. It would commence the morning of 20 July with two companies of the 1st Raider Battalion and all of the 4th advancing from Enogai while the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry, moved out along the Triri Bairoko Trail. The American forces would converge on the Japanese from two directions. The remaining Army battalion guarded Triri; Companies A and C of the raiders defended Enogai. These units also served as the reserve. Liversedge requested an air-strike on Bairoko timed to coincide with the attack, but it never materialized. The movement toward Bairoko kicked off at 0800 and the 1st Raider Battalion made contact with enemy outposts two hours later. Companies B and D deployed into line and pushed through a series of Japanese outguards. By noon Griffith's men had reached the main defenses, which consisted of four fortified lines on parallel coral ridges just a few hundred yards from the harbor. The bunkers were mutually supporting and well protected by coconut logs and coral. Each held a machine gun or automatic weapon. Here the 1st Battalion's attack ground to a halt. Liversedge, accompanying the northern prong of his offensive, committed the 4th Battalion in an attempt to turn the enemy flank, but it met the same heavy resistance. The raider companies slowly worked their way forward, and by late after noon they had seized the first two enemy lines. However, throughout this advance enemy 90mm mortar fire swept the Marine units and inflicted numerous casualties. The southern prong of the attack was faring less well. The Army battalion made its first contact with the enemy just 1,000 yards from Bairoko, but the Japanese held a vital piece of high ground that blocked the trail. With the lagoon on one side and a deep swamp on the other, there was no room for the soldiers to maneuver to the flanks of the enemy position. With the approval of the executive officer of the raider regiment, the commander of the Army battalion pulled back his lead units and used his two 81mm mortars to soften the defenses.

When news of the halt in the southern attack made it to Liversedge at 1600, he asked the commanders of the raider battalions for their input. Griffith and Currin checked their lines. They were running out of water and ammunition, casualties had been heavy, and there was no friendly fire support. Neither battalion had any fresh reserves to commit to the fight. Moreover, a large number of men would be needed to hand-carry the many wounded to the rear. The 4th Raiders alone had 90 litter cases. From their current positions on high ground the Marine commanders could see the harbor just a few hundred yards away, but continued attacks against a well-entrenched enemy with fire superiority seemed wasteful. Not long after 1700 Liversedge issued orders for all battalions to pull back into defensive positions for the night in preparation for a withdrawal to Enogai and Triri the next day. He requested air strikes to cover the latter movement.

The move back across Dragons Peninsula on 21 July went smoothly from a tactical point of view. After failing to provide air support for the attack, higher echelons sent 250 sorties against Bairoko to cover the withdrawal. The Japanese did not pursue, but even so it was tough going on the ground. Water was in short supply and everyone had to take turns carrying litters. The column moved slowly and halted every few hundred yards. In the afternoon rubber boats picked up most of the wounded and ferried them to the rear. By that evening the entire force was back in its enclaves at Enogai and Triri. PBYs made another trip to evacuate wounded, though this time two Zero fighters damaged one of the amphibian planes after take-off and forced it to return to Enogai Inlet. Total American casualties were 49 killed, 200 wounded, and two missing — the vast majority of them suffered by the raider battalions. The failure to seize the objective and the severe American losses were plainly the result of poor logistics and a lack of firepower. A Joint Chiefs of Staff post mortem on the operation noted that "lightly armed troops cannot be expected to attack fixed positions defended by heavy automatic weapons, mortars, and heavy artillery." Another factor of significance, however, was the absence of surprise. The raiders had taken Enogai against similar odds because the enemy had not expected an attack from anywhere but the sea. Victory at Enogai provided ample warning to the garrison at Bairoko, and the Japanese there made themselves ready for an overland assault. The raiders might still have won with a suicidal effort, but Bairoko was not worth it.

The 1st Raider Regiment and its assorted battalions settled into defensive positions for the rest of July. The sole action consisted of patrols toward Bairoko and nuisance raids from Japanese aircraft. In early August elements of the force took up new blocking positions on the Munda-Bairoko Trail. On 9 August they made contact with Army troops from the Southern Landing Group. (Munda Airfield had fallen four days earlier.) Later in the month two Army battalions moved cautiously against Bairoko and found their way barred by only an occasional small outpost. The main enemy force had escaped by sea and the soldiers took control of the harbor on 24 August. The raider headquarters and both Marine battalions embarked in transports on 28 August and sailed for Guadalcanal. The New Georgia campaign had been a costly one. Each raider battalion had suffered battle casualties of more than 25 percent. In addition, sickness had claimed an even greater number. The 1st Raiders now had just 245 effectives; the 4th Raiders only 154.

|