Climate and Weather

Climate plays a crucial role in driving or regulating many ecological processes. It helps determine which plant species occur where; how nutrients, water, and energy are cycled; and the relationships between soil, plants, and water availability. Climate can also affect the susceptibility of an ecosystem to myriad disturbances, such as floods, drought, and wildfire.

Plants and animals are adapted both to the short-term variability of weather and to the long-term climate conditions in the places where they live. But if extreme weather or changes in climate exceed their ability to cope, they will move, suffer, or perish. Both weather and climate help shape the distribution of plants and animals across the landscape. For example, weather conditions affect wildfires, the timing and volume of streamflow, and plant growth. Climate, such as hot, arid conditions on a high plateau, affects which plants and animals live there and how quickly they grow and reproduce.

Climate and Weather: What's the Difference?

“Climate is what you expect. Weather is what you get.” Weather and climate describe the same thing—the state of the atmosphere—but at different time scales. Weather is what you experience when you step outside on any given day. In other words, it is the state of the atmosphere at a particular location over the short-term. Climate is the average of the weather patterns in a location over a longer period of time, usually 30 years or more. When we talk about climate change, we are talking about changes in long-term averages of daily weather; if most days are warmer, then the long-term average will be warmer.

Climate Monitoring

Because climate, weather, and natural resource vital signs are all intricately linked, the Northern Colorado Plateau Network studies them simultaneously. Understanding how park vital signs responded to past conditions provides clues about how they may respond in the future. We track climate using weather station data from network parks. But climate is more than just temperature and precipitation, so we also calculate “water balance”—the amount of water available for use by plants. Real-time weather and water balance conditions, along with historical summaries, are reported through an interactive website, The Climate Analyzer.

Water Balance

Plants don’t “drink” rain; they use water from soil taken up by their roots. So instead of just recording how much water falls from the sky, it’s important to determine how much of that water is actually available to plants at any given time. Starting with the total precipitation, NCPN staff use a model to subtract runoff, drainage, and evaporation. The remaining water, stored in soil, can be used by plants. Tracking how precipitation moves through the environment in its different forms (liquid, solid, gas) has improved our understanding of vegetation response to past weather and climate patterns. This in turn has vastly improved our ability to understand potential climate-change impacts to plants and animals in parks.

Climate Change

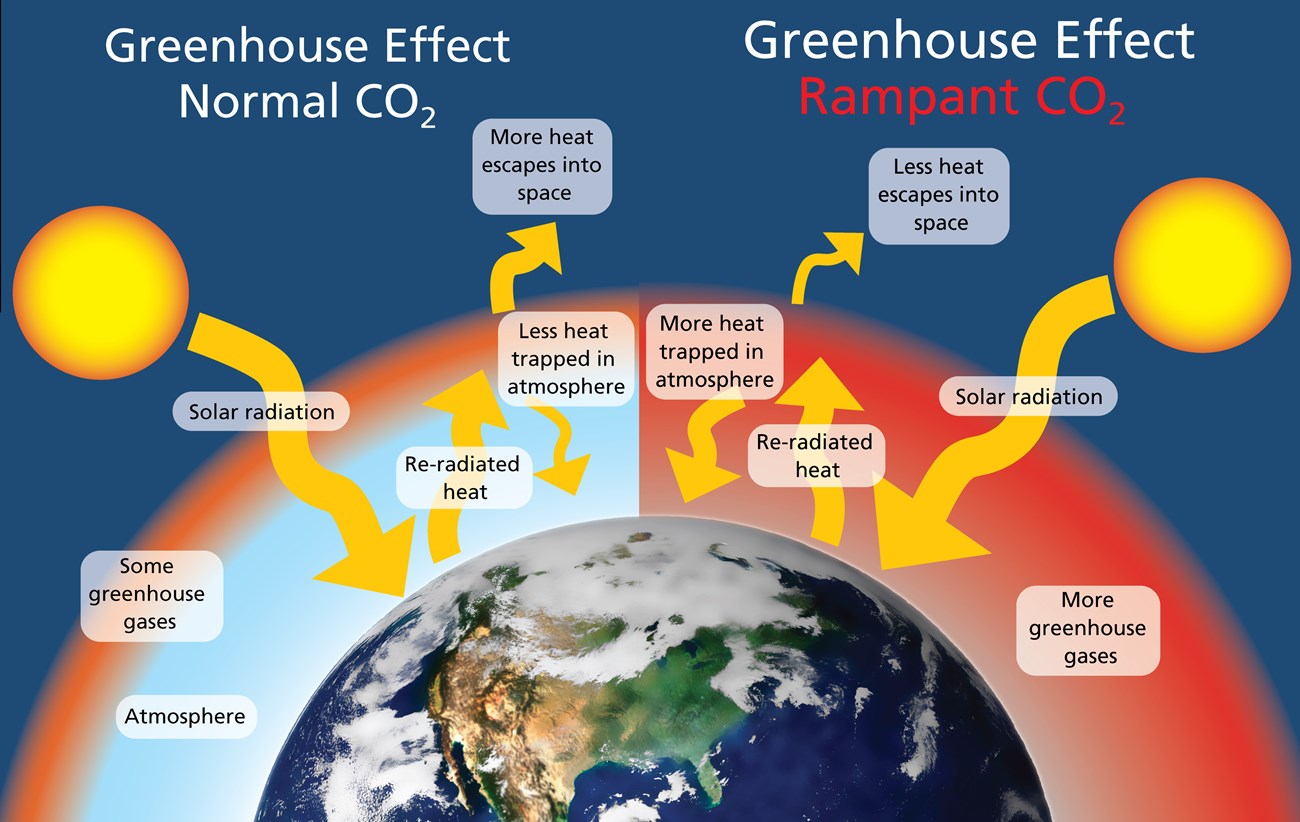

Twenty-first century climate change is unique in its magnitude, pace, and projected impacts. Scientists attribute the global warming trend observed since the mid-20th century to the human expansion of the "greenhouse effect:" warming that results when the atmosphere traps heat radiating from Earth toward space. On Earth, human activities are changing the natural greenhouse. Over the last century, the burning of fossil fuels like coal and oil has increased the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). This happens because the coal or oil burning process combines carbon with oxygen in the air to make CO2. To a lesser extent, the clearing of land for agriculture, industry, and other human activities has increased concentrations of greenhouse gases. The consequences of changing the natural atmospheric greenhouse include warmer average temperatures, more extreme weather events, sea level rise, shifts in ocean circulation and chemistry, and increased drought stress. These impacts can strengthen and amplify one another.

|

Left: Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are created by normal life processes, trapping some of the sun's heat and preventing the planet from freezing.

Right: The rampant emission of CO2 from burning fossil fuels traps excess heat, leading to increases in average temperature and a cascade of other effects. The solution is to reduce human activities that emit heat-trapping gases.

Graphic: NPS/William Elder |

Climate change is no longer a future threat. On the Northern Colorado Plateau, we are currently seeing its consequences reflected in changes to vegetation and water resources. In the future, the Northern Colorado Plateau will likely get warmer and drier, because potential increases in precipitation will likely be offset by warming temperatures that will increase evaporation rates and water use by plants ("evapotranspiration"). Climate change will affect the distribution of plants and animals in parks, which will change how ecosystems work. All of the natural resource vital signs in NCPN parks are affected by climate change.

To help park managers prepare for these and other changes, the NCPN and its partners, such as the NPS Climate Change Response Program, are helping park managers to determine the sensitivity of park resources to a changing climate. For instance, our work is helping managers know which types of plants may be more resilient to projected climate changes. Understanding where and what to plant as the climate gets drier—and where and what to let go—will help managers decide which plant communities to prioritize for restoration, so parks don’t waste time and money planting species that are unlikely to survive. Adaptive decision making like this is part of a process called Climate Smart Conservation, which helps land managers understand sensitivity to climate, identify adaptation strategies, and implement those likely to reduce vulnerabilities and meet forward-looking management goals. Network staff are actively helping parks engage in this process.

With tools provided by The Climate Analyzer, we can also do forecasting and nowcasting of vegetation condition a few months into the future based on our understanding of how vegetation response lags weather conditions. Park managers could use this model to help predict the months and years in which projects that depend on good growing conditions might be most likely to succeed. The model may also help predict the short-term impacts of drought on vegetation.

Learn more about the causes and effects of climate change at these web sites:

- NPS Climate Change subject site

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- U.S. Climate Change Science Program

- NASA Global Climate Change Program

- NOAA climate change hub

- USGS Western Geographic Science Center

Vital Signs: Climate and weather

Protocol Lead: Dusty Perkins

Quick Reads

Publications and Other Information

Source: NPS DataStore Collection 4266. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 472. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 449. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Source: NPS DataStore Collection 2543. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Last updated: December 18, 2025